Kenneth Riley, CA

(1919-2015)

As a young art student, Ken Riley had the opportunity to study with Harvey Dunn; one of America’s most influential artists and teachers. Riley attended Dunn’s evening workshops at Grand Central School of Art in New York while studying at the Art Students League during the day. Dunn had been part of Howard Pyle’s studio in Wilmington, Delaware, where luminaries such as N. C. Wyeth and Frank Schoonover also trained. Riley also studied for one year with American artist Thomas Hart Benton.

Riley is a direct link between the great Western artists of the late nineteenth century and the Western artists of the contemporary scene. He has been a member of the Cowboy Artists of America since 1982 and has worked and painted alongside some of the twentieth century’s finest interpreters of the American West; including Robert Lougheed, John Clymer, and Donald Teague.

In the late 1960s, after working as an illustrator for many years on the East Coast, he was commissioned by the U.S. Park Service to create several paintings of the Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks. During that time, he decided to devote his work solely to Western subjects. “Those trips,” he says, “convinced me that the West was where I wanted to live and work.” In 1973, Riley moved to Tucson, Arizona, and he has been there every since.

Early in his career, Riley painted a wide range of historical Western subjects, but during the past several years, he has concentrated almost solely on Native American subjects. He has gradually moved away from direct narrative treatments to allegorical studies of Indian life and culture. A master of design, composition, and color, Riley has developed a style of work that is immediately recognizable. He won the Prix de West award at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in 1995. He was the first recipient of the Eiteljorg Museum Award for excellence in American art. Riley’s paintings hang in the permanent collections of the White House and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

Source: Cowboy Artist of America

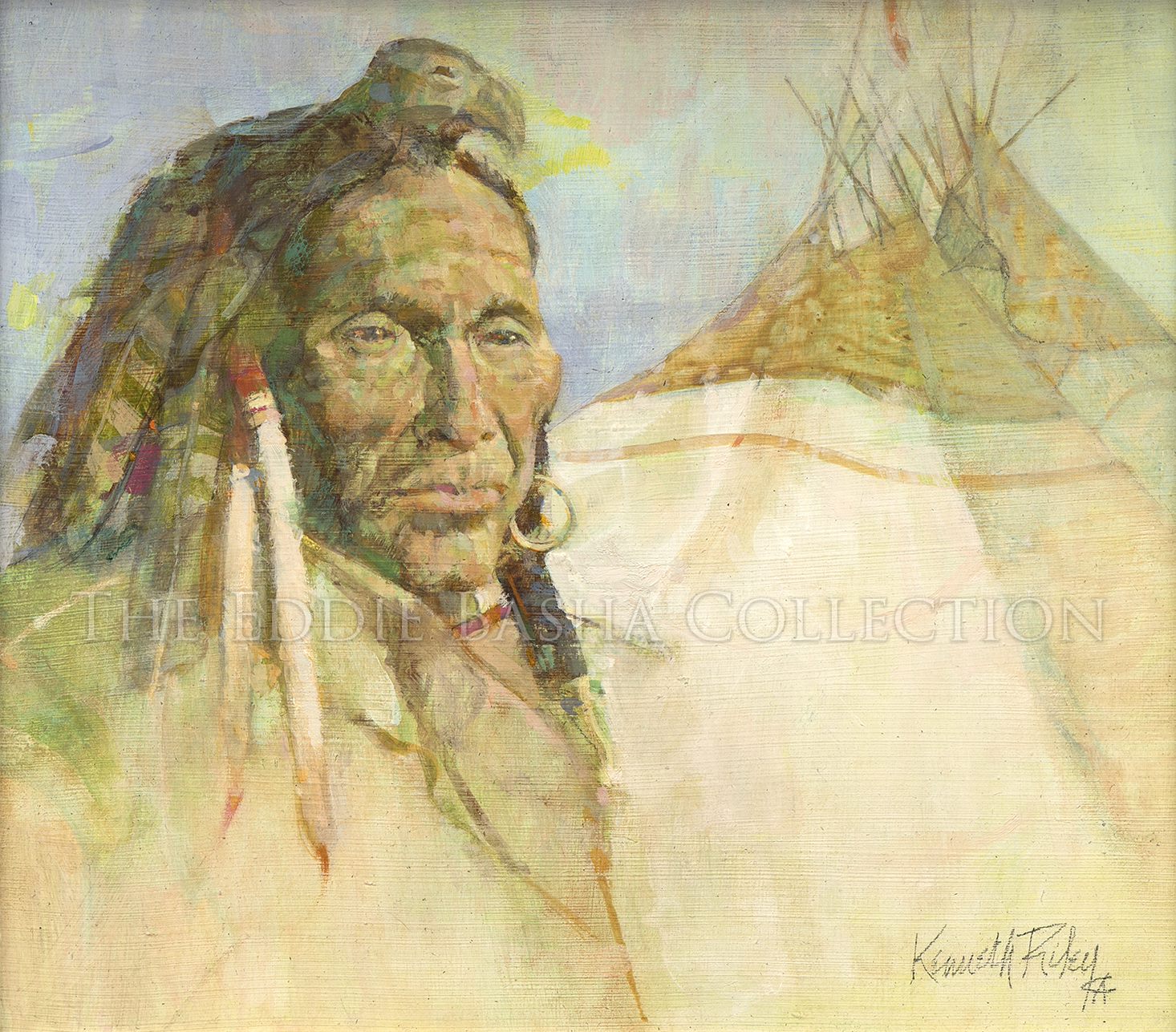

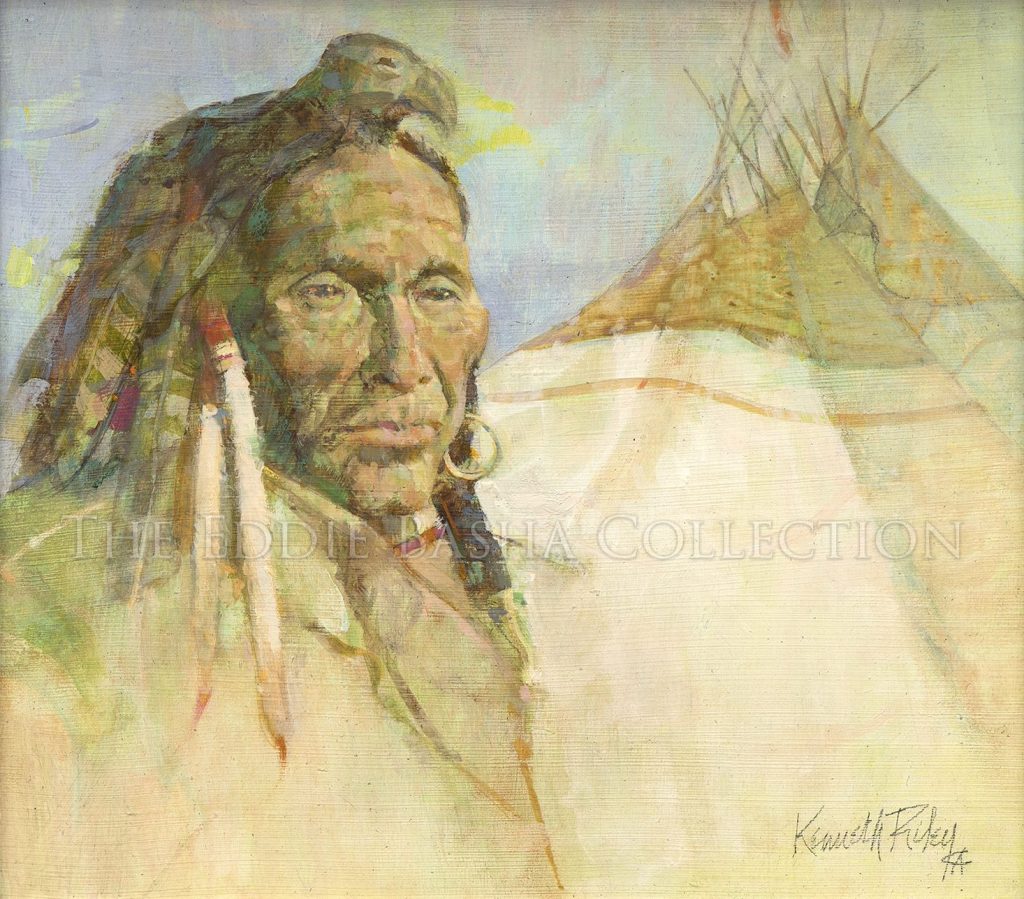

Unknown Title

Artist: Kenneth Riley, CA (1919-2015)

Description: Oil | Image Size: 8”h x 9”w; Framed Size: 12 ½"h x 13 ½"wpainting

This small study of an Indian portrait is emblematic of Ken Riley’s capacity to render the individualism and personality of his subjects. The weathered yet learned face of the Indian is the focal point of the painting while the background teepees add visual interest. The striking bird headdress adds to the subject’s presence, prominence and power and is a wonderful visual component that speaks to the time period. Indeed, Riley delivered composition, color, and content!

Riley enjoyed a long and successful career as both an illustrator, working for various publications such as National Geographic

and The Saturday Evening Post, and as a professional fine artist. The National Park Service commissioned him to do a series of paintings on Yellowstone National Park and Yosemite National Park, assignments which introduced him to the rugged beauty of the American West. Shortly after his national park commission, he moved West and began focusing solely on painting scenes from American Indian and Western American History. He was an award-winning charter

member of the National Academy of Western Art, the Cowboy Artists of America, and a frequent participant in national exhibitions. His work can be found in public and private collections worldwide.

Camelot

Artist: Kenneth Riley, CA (1919-2015)

Description: Oil | Image Size: 34”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 46”h x 51”wpainting

Of this painting and book cover image of “West of Camelot: The Historical Paintings of Kenneth Riley,” published by The Eiteljorg Museum of American Indian &Western Art in 1993, authored by Susan Hallsten McGarry, the artist shared “On a trip to Morocco, my wife and I attended the re-creation of a competition honoring the king. Tents and flying banners were filled with exotic weavings and adornments, providing a magnificent setting for Berber horsemen who fired antique muskets and rode with the pomp and ceremony of the ages. The pageantry of the Berbers has a parallel among the Plains Indians, who likewise decorated themselves and their mounts in celebration of a successful war party or in preparation for a parade on horseback at the midsummer Sun Dance. Beadwork glinting in the sun, ermine fringes and scalp locks flying in the wind, along with painted shields, beaded bow cases and feathered war bonnets and lances must have presented a formidable spectacle of not only power and status, but color and texture.”

This magnificent painting of a Plains Indian warrior dressed in full ceremonial regalia is one of Ken Riley’s finest achievements. The central figure is resplendent astride his proud white horse adorned with traditional symbols of power and bravery. By shrouding the background in a swirling dust cloud, several elements added to the overall impact of the painting. For one, the dust obscures other figures in the scene, but heightens our focus on the warrior. And the swirling dust and ghostly images of the other ceremonial participants in the background give a sense of movement and the perception that we, as the viewer, are smack-dab in the middle of the ceremony.

Cowboy Artists of America Member 1982-2015.

Return of the Coldmaker

Artist: Kenneth Riley, CA (1919-2015)

Description: Oil (1999) | Image Size: 48”w x 42”w; Framed Size: 56”h x 50”wpainting

Among the Blackfeet of the Northern Plains, there was passed from generation to generation the legend of the Coldmaker. As fall winds start to chill, elders told of an old person riding down from the far north country. With wolves as his companions, he brought winter snows to cover the plains and the cold forcing native people to seek warmth in their buffalo lodges. Thus, the winter season remained until the Coldmaker eventually rode north and the warming new sun renewed their land.

In “A General View of the Fine Arts” published by G.P. Putnam in 1851, Anna Douglas Ludlow wrote: “Historical painting is the noblest and most comprehensive branch of art, as it embraces man, the head of the visible creation. The historical painter, therefore, must study man, from the anatomy of his figure, to the most rapid and slightest gesture expressive of feeling, or the display of deep and subtle passions. He must have technical skill, a practiced eye and hand, and must understand so to group his skillfully executed parts as to produce a beautiful whole. And all of this is insufficient without a poetic spirit, which can form a striking conception of historical events, or create imaginary scenes of beauty.”

Truer words couldn’t be more relevant when applying them to Ken Riley’s depiction of the Blackfeet’s natural world legend that brings the snow in “Return of the Coldmaker”. Its technically executed parts produced a beautiful whole; a poetically spiritual imaginary scene of beauty.

Reflections

Artist: Kenneth Riley, CA (1919-2015)

Description: Oil (1999) | Image Size: 16”h x 16”w; Framed Size: 24”h x 24”wpainting

Kenneth Riley (1919-2015) painted a very detailed and realistic portrait of a Northern Plains Indian complete with a bear claw necklace and horned, feather headdress. The ribbons that hang from one of the horns frame the subject’s face. Even as the warrior gazes downward, his entire face is visible to the viewer. It is a dramatic portrait made even more so by Riley’s use of vivid, saturated reds that command attention.

Riley’s “Reflections” made its debut at the 34th Annual Cowboy Artists of America Exhibition & Sale in 1999 at the Phoenix Art Museum. This masterwork will be relocating to Western Spirit: Scottsdale Museum of the West.

Oil | Image Size: 8”h x 9”w; Framed Size: 12 ½"h x 13 ½"w

Oil | Image Size: 8”h x 9”w; Framed Size: 12 ½"h x 13 ½"w This small study of an Indian portrait is emblematic of Ken Riley’s capacity to render the individualism and personality of his subjects. The weathered yet learned face of the Indian is the focal point of the painting while the background teepees add visual interest. The striking bird headdress adds to the subject’s presence, prominence and power and is a wonderful visual component that speaks to the time period. Indeed, Riley delivered composition, color, and content!

Riley enjoyed a long and successful career as both an illustrator, working for various publications such as National Geographic

and The Saturday Evening Post, and as a professional fine artist. The National Park Service commissioned him to do a series of paintings on Yellowstone National Park and Yosemite National Park, assignments which introduced him to the rugged beauty of the American West. Shortly after his national park commission, he moved West and began focusing solely on painting scenes from American Indian and Western American History. He was an award-winning charter

member of the National Academy of Western Art, the Cowboy Artists of America, and a frequent participant in national exhibitions. His work can be found in public and private collections worldwide.

Unknown Title

Artist: Kenneth Riley, CA (1919-2015)

This small study of an Indian portrait is emblematic of Ken Riley’s capacity to render the individualism and personality of his subjects. The weathered yet learned face of the Indian is the focal point of the painting while the background teepees add visual interest. The striking bird headdress adds to the subject’s presence, prominence and power and is a wonderful visual component that speaks to the time period. Indeed, Riley delivered composition, color, and content!

Riley enjoyed a long and successful career as both an illustrator, working for various publications such as National Geographic

and The Saturday Evening Post, and as a professional fine artist. The National Park Service commissioned him to do a series of paintings on Yellowstone National Park and Yosemite National Park, assignments which introduced him to the rugged beauty of the American West. Shortly after his national park commission, he moved West and began focusing solely on painting scenes from American Indian and Western American History. He was an award-winning charter

member of the National Academy of Western Art, the Cowboy Artists of America, and a frequent participant in national exhibitions. His work can be found in public and private collections worldwide.

Oil | Image Size: 34”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 46”h x 51”w

Oil | Image Size: 34”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 46”h x 51”wOf this painting and book cover image of “West of Camelot: The Historical Paintings of Kenneth Riley,” published by The Eiteljorg Museum of American Indian &Western Art in 1993, authored by Susan Hallsten McGarry, the artist shared “On a trip to Morocco, my wife and I attended the re-creation of a competition honoring the king. Tents and flying banners were filled with exotic weavings and adornments, providing a magnificent setting for Berber horsemen who fired antique muskets and rode with the pomp and ceremony of the ages. The pageantry of the Berbers has a parallel among the Plains Indians, who likewise decorated themselves and their mounts in celebration of a successful war party or in preparation for a parade on horseback at the midsummer Sun Dance. Beadwork glinting in the sun, ermine fringes and scalp locks flying in the wind, along with painted shields, beaded bow cases and feathered war bonnets and lances must have presented a formidable spectacle of not only power and status, but color and texture.”

This magnificent painting of a Plains Indian warrior dressed in full ceremonial regalia is one of Ken Riley’s finest achievements. The central figure is resplendent astride his proud white horse adorned with traditional symbols of power and bravery. By shrouding the background in a swirling dust cloud, several elements added to the overall impact of the painting. For one, the dust obscures other figures in the scene, but heightens our focus on the warrior. And the swirling dust and ghostly images of the other ceremonial participants in the background give a sense of movement and the perception that we, as the viewer, are smack-dab in the middle of the ceremony.

Cowboy Artists of America Member 1982-2015.

Camelot

Artist: Kenneth Riley, CA (1919-2015)

Of this painting and book cover image of “West of Camelot: The Historical Paintings of Kenneth Riley,” published by The Eiteljorg Museum of American Indian &Western Art in 1993, authored by Susan Hallsten McGarry, the artist shared “On a trip to Morocco, my wife and I attended the re-creation of a competition honoring the king. Tents and flying banners were filled with exotic weavings and adornments, providing a magnificent setting for Berber horsemen who fired antique muskets and rode with the pomp and ceremony of the ages. The pageantry of the Berbers has a parallel among the Plains Indians, who likewise decorated themselves and their mounts in celebration of a successful war party or in preparation for a parade on horseback at the midsummer Sun Dance. Beadwork glinting in the sun, ermine fringes and scalp locks flying in the wind, along with painted shields, beaded bow cases and feathered war bonnets and lances must have presented a formidable spectacle of not only power and status, but color and texture.”

This magnificent painting of a Plains Indian warrior dressed in full ceremonial regalia is one of Ken Riley’s finest achievements. The central figure is resplendent astride his proud white horse adorned with traditional symbols of power and bravery. By shrouding the background in a swirling dust cloud, several elements added to the overall impact of the painting. For one, the dust obscures other figures in the scene, but heightens our focus on the warrior. And the swirling dust and ghostly images of the other ceremonial participants in the background give a sense of movement and the perception that we, as the viewer, are smack-dab in the middle of the ceremony.

Cowboy Artists of America Member 1982-2015.

Oil (1999) | Image Size: 48”w x 42”w; Framed Size: 56”h x 50”w

Oil (1999) | Image Size: 48”w x 42”w; Framed Size: 56”h x 50”wAmong the Blackfeet of the Northern Plains, there was passed from generation to generation the legend of the Coldmaker. As fall winds start to chill, elders told of an old person riding down from the far north country. With wolves as his companions, he brought winter snows to cover the plains and the cold forcing native people to seek warmth in their buffalo lodges. Thus, the winter season remained until the Coldmaker eventually rode north and the warming new sun renewed their land.

In “A General View of the Fine Arts” published by G.P. Putnam in 1851, Anna Douglas Ludlow wrote: “Historical painting is the noblest and most comprehensive branch of art, as it embraces man, the head of the visible creation. The historical painter, therefore, must study man, from the anatomy of his figure, to the most rapid and slightest gesture expressive of feeling, or the display of deep and subtle passions. He must have technical skill, a practiced eye and hand, and must understand so to group his skillfully executed parts as to produce a beautiful whole. And all of this is insufficient without a poetic spirit, which can form a striking conception of historical events, or create imaginary scenes of beauty.”

Truer words couldn’t be more relevant when applying them to Ken Riley’s depiction of the Blackfeet’s natural world legend that brings the snow in “Return of the Coldmaker”. Its technically executed parts produced a beautiful whole; a poetically spiritual imaginary scene of beauty.

Return of the Coldmaker

Artist: Kenneth Riley, CA (1919-2015)

Among the Blackfeet of the Northern Plains, there was passed from generation to generation the legend of the Coldmaker. As fall winds start to chill, elders told of an old person riding down from the far north country. With wolves as his companions, he brought winter snows to cover the plains and the cold forcing native people to seek warmth in their buffalo lodges. Thus, the winter season remained until the Coldmaker eventually rode north and the warming new sun renewed their land.

In “A General View of the Fine Arts” published by G.P. Putnam in 1851, Anna Douglas Ludlow wrote: “Historical painting is the noblest and most comprehensive branch of art, as it embraces man, the head of the visible creation. The historical painter, therefore, must study man, from the anatomy of his figure, to the most rapid and slightest gesture expressive of feeling, or the display of deep and subtle passions. He must have technical skill, a practiced eye and hand, and must understand so to group his skillfully executed parts as to produce a beautiful whole. And all of this is insufficient without a poetic spirit, which can form a striking conception of historical events, or create imaginary scenes of beauty.”

Truer words couldn’t be more relevant when applying them to Ken Riley’s depiction of the Blackfeet’s natural world legend that brings the snow in “Return of the Coldmaker”. Its technically executed parts produced a beautiful whole; a poetically spiritual imaginary scene of beauty.

Oil (1999) | Image Size: 16”h x 16”w; Framed Size: 24”h x 24”w

Oil (1999) | Image Size: 16”h x 16”w; Framed Size: 24”h x 24”wKenneth Riley (1919-2015) painted a very detailed and realistic portrait of a Northern Plains Indian complete with a bear claw necklace and horned, feather headdress. The ribbons that hang from one of the horns frame the subject’s face. Even as the warrior gazes downward, his entire face is visible to the viewer. It is a dramatic portrait made even more so by Riley’s use of vivid, saturated reds that command attention.

Riley’s “Reflections” made its debut at the 34th Annual Cowboy Artists of America Exhibition & Sale in 1999 at the Phoenix Art Museum. This masterwork will be relocating to Western Spirit: Scottsdale Museum of the West.

Reflections

Artist: Kenneth Riley, CA (1919-2015)

Kenneth Riley (1919-2015) painted a very detailed and realistic portrait of a Northern Plains Indian complete with a bear claw necklace and horned, feather headdress. The ribbons that hang from one of the horns frame the subject’s face. Even as the warrior gazes downward, his entire face is visible to the viewer. It is a dramatic portrait made even more so by Riley’s use of vivid, saturated reds that command attention.

Riley’s “Reflections” made its debut at the 34th Annual Cowboy Artists of America Exhibition & Sale in 1999 at the Phoenix Art Museum. This masterwork will be relocating to Western Spirit: Scottsdale Museum of the West.