William Ahrendt

(b. 1933)

William Ahrendt was born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1933. He holds a Master’s degree in Art History from Arizona State University and a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in painting from the Cleveland Institute of Art where he won the Institute’s coveted European Study Scholarship.

William resided in Europe for eleven years, living mostly in Germany where he attended the Munich Fine Arts Academy of Creative Art and studied painting techniques of the Renaissance and Baroque periods. His style is that of the Old Masters, and he begins a painting by mixing and applying a batch of egg tempera as the foundation, building light and dark. Later he applies layers of oil paint, and the result is a painting that glows; It a technique he learned in Munich.

In 1968, William returned to America with his German born wife, Renate, and brought her to the family home in Arizona. He became the Art Department Chairperson at Glendale Community College from which he retired in 1979 to concentrate on his fine art career. William has been contributing editor for “Arizona Highways” magazine where his paintings and historical articles have been published in over 40 issues. He was featured in “Southwest Art” magazine June 1994 and “Art of the West” magazine May 1999.

Source: Legacy Gallery

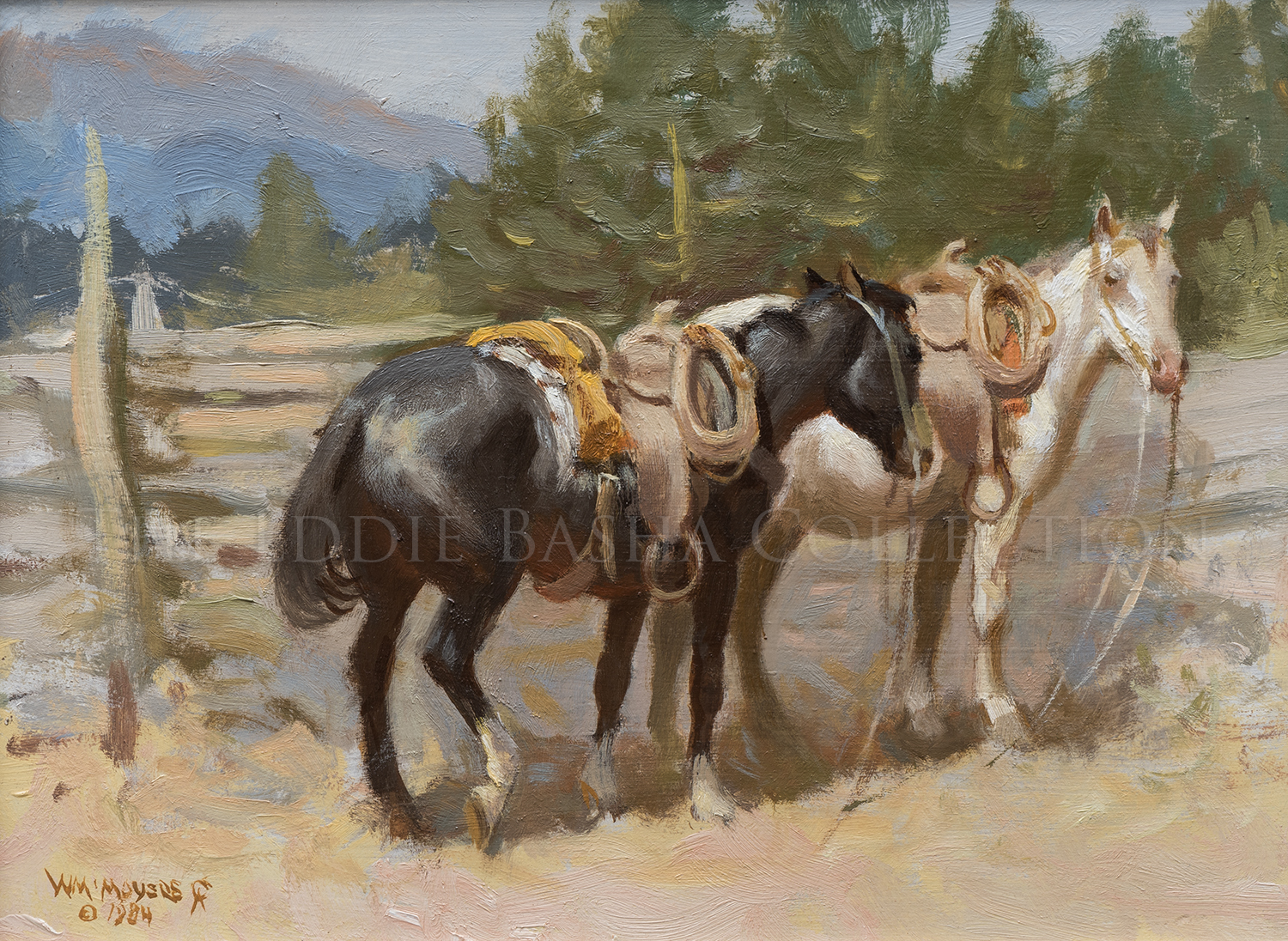

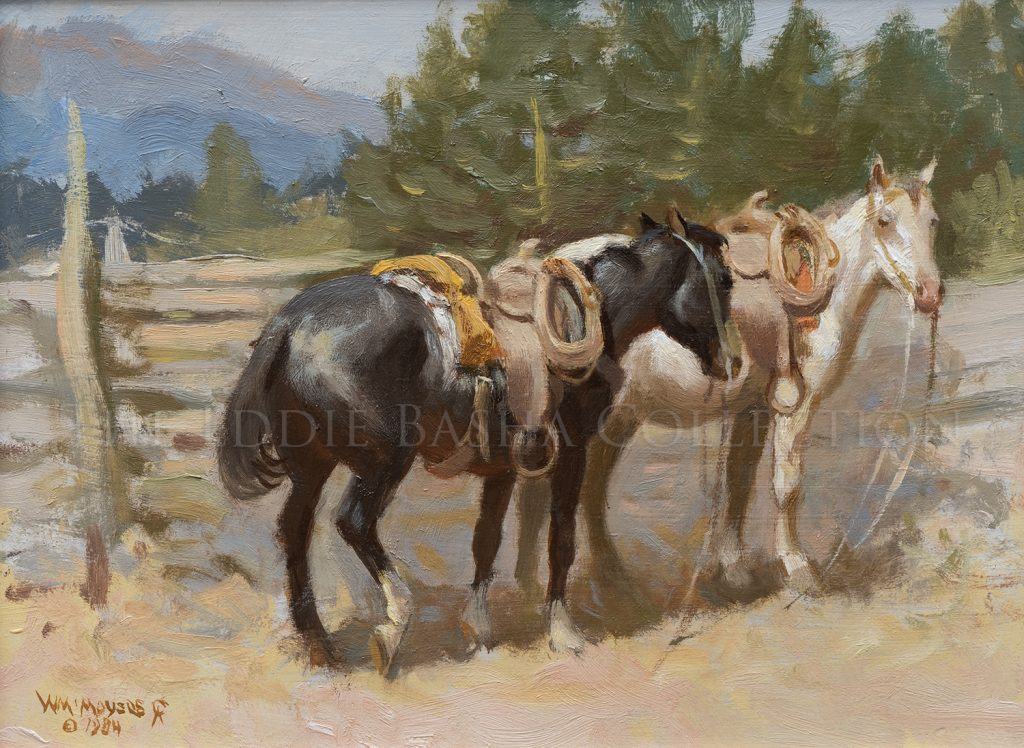

Waiting

Artist: William "Bill" Ahrendt (b. 1933)

Description: Oil on Board (1984) | Image Size: 9h x 12w; Framed Size: 16”h x 18 ¾”wpainting

William Moyers had first-hand knowledge of working ranch horses having spent much of his teenage years as a cowhand on a Colorado ranch. After becoming a professional artist, he often called upon that knowledge to create realistic and authentic scenes such as this one. Here, two horses, fully saddled and equipped for range work, stand beside a wood rail fence patiently waiting for their riders to return. For the ponies, and the cowboys who will ride them, this scene in Colorado or the New Mexico high country, is simply a brief respite before their work continues. Moyers effectively contrasts the colors of the ponies, one dark and one white, to focus the viewer’s attention on the center of the painting. In the far background, he shows distant mountains that add to the sense of authenticity in the landscape.

An early member of the Cowboy Artists of America, William Moyers excelled as both a painter and sculptor. Born in Atlanta, he moved to Colorado as a teenager and that work paid for his education at Adams State College in Alamosa, Colorado. After graduation, he studied at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles and then worked in the animation department at Walt Disney Studios. Following his service during World War II, he and his wife moved to New York and then back to his hometown of Atlanta where he pursued a successful career as an illustrator of western subjects. By the early 1960’s he moved away from the illustration business to concentrate on his own art work. His career as a western artist spanned a half century and his work can be found in the many museums as well as private collections. Moyers won several awards in both sculpting and painting at the annual exhibitions and sales of the Cowboy Artists of America and served as that organization’s president on three occasions.

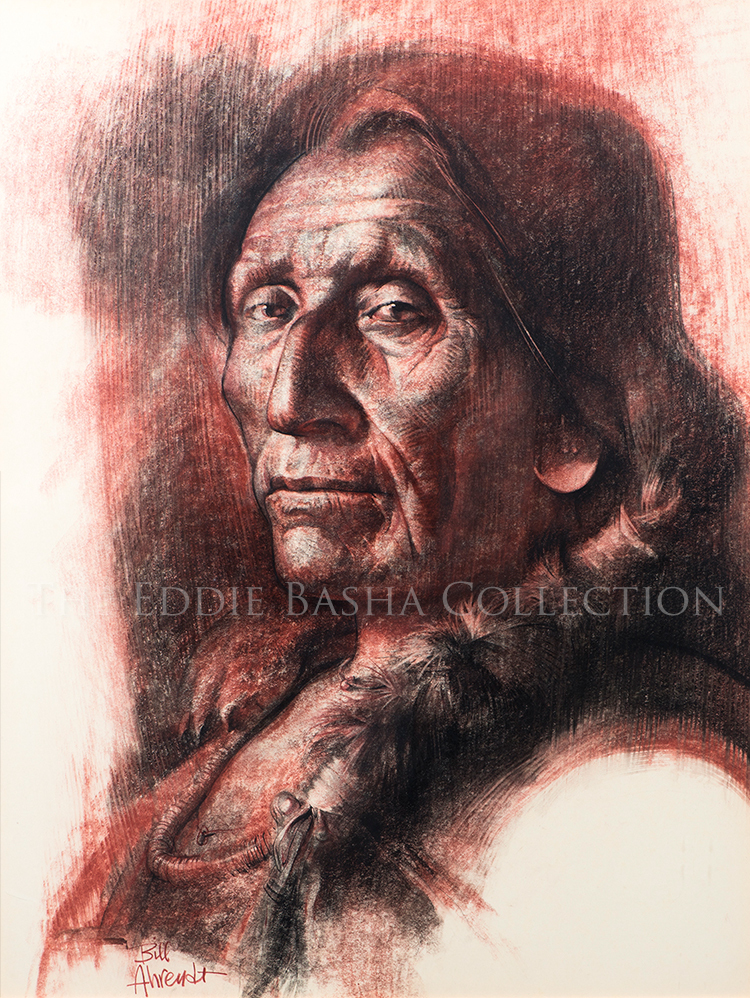

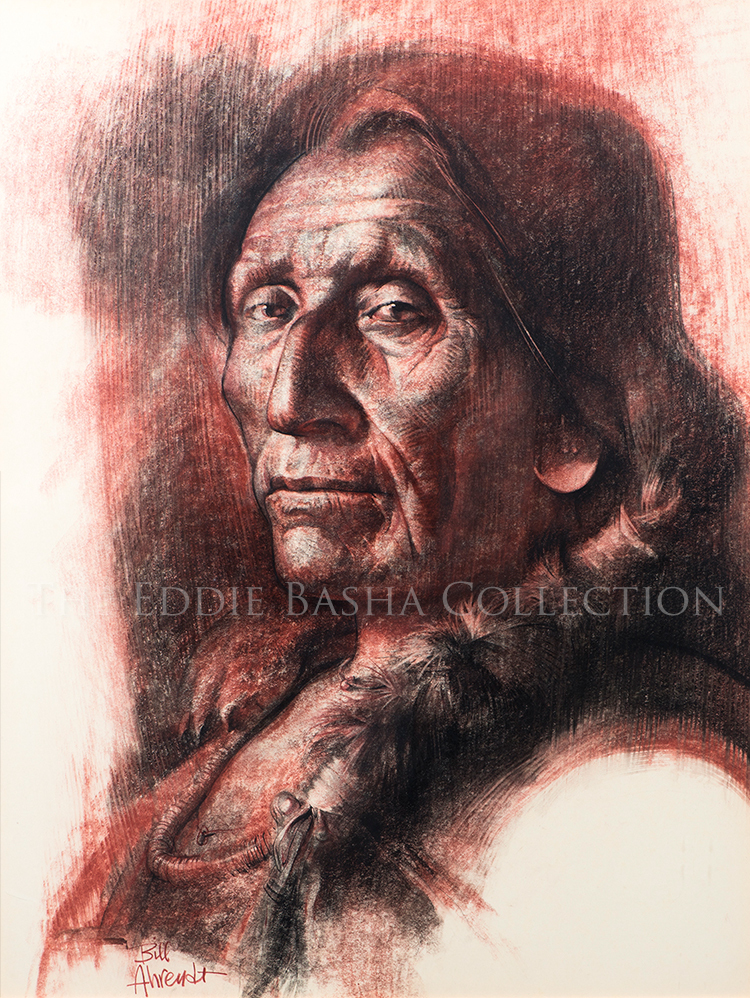

Little Robe

Artist: William "Bill" Ahrendt (b. 1933)

Description: Conte Crayon (1985) | Image Size: 25”h x 20”w; Framed Size: 34 ½”h x 28 5/8”wdrawing

Little Robe (Ski-o-mah), Southern Cheyenne, was born in about 1828, became a noted young warrior during combat against traditional enemies. His first tribal distinction came after a battle with Pawnee in Kansas in 1852, when he was given the honor of carrying from camp to camp the pipe of mourning in memory of those lost in the engagement. He became a chief around 1863. Colonel John Chivington, 3rd Colorado Volunteer Cavalry, claimed to have killed Little Robe at Sand Creek, Colorado, but reports of his death were greatly exaggerated.

The massacre compelled Little Robe to wage war against whites, but he soon came to the conclusion that such actions were hopeless. He participated in the April 1867 council with General Winfield S. Hancock at Fort Larned, Kansas, and then worked with Chief Black Kettle in an effort to persuade militant brethren to join them in signing the Medicine Lodge Treaty in October 1867.

In November 1868, Little Robe accompanied Black Kettle and other chiefs to Fort Cobb, Indian Territory, to talk peace with Colonel William Hazen, but were told that they had to make peace with General Phillip Sheridan to ensure their safety as he was in the field. The chiefs returned to their camp on the Washita River, and discussed what was said with their tribal council. When Black Kettle was killed during the attack by the 7th U.S. Cavalry, Little Robe initially supported the hostiles. In March 1869, he was camped at Sweetwater Creek, Texas, and met with Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer, who was attempting to secure the release of two captive white women from a nearby village. Later that spring, Little Robe surrendered at Fort Cobb, and assumed the role of principle chief of the peace faction.

Chief Little Robe was a member of delegations that toured Washington, D.C., and other eastern cities both in 1871 and 1873. He met President U.S. Grant on the second trip. He once again was a voice for peace during the Red River War of 1874-75, refusing to leave his reservation home in the Indian Territory on the North Canadian River. Although he was a proponent of peace with whites, he would not send children from his tribe to white schools. Little Robe (Ski-o-mah) died peacefully in 1886. (Ref. National Park Service, Washita Battlefield, National Historic Site, OK)

Bill Ahrendt’s skill in capturing the personality of Little Robe is fully evident in this portrait. While paying attention to details of clothing and hair style, Arhendt also focused on Little Robe’s face; the furrowed brow and lines around his eyes reveal both his character and reflect a lifetime of experiences.

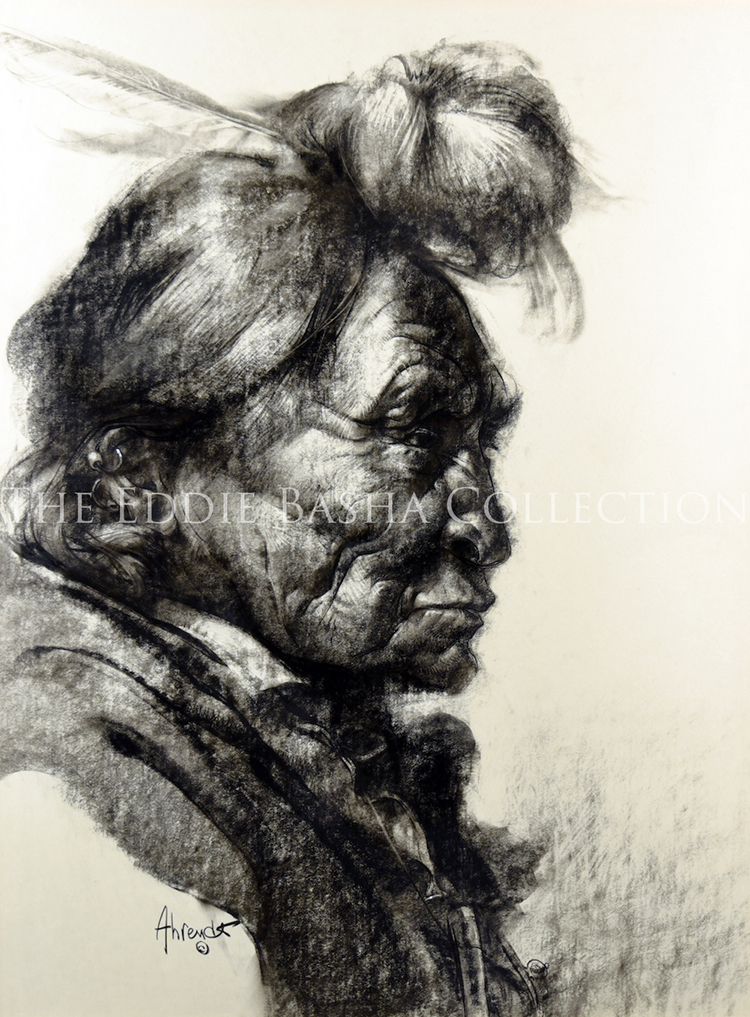

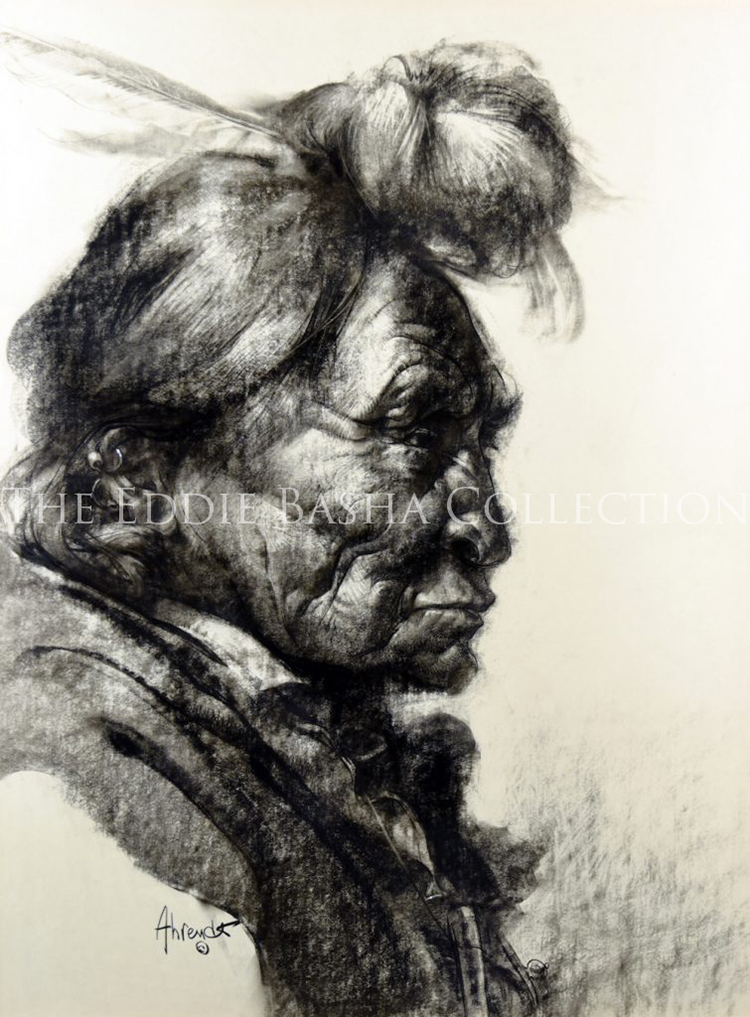

Unknown Title

Artist: William "Bill" Ahrendt (b. 1933)

Description: Conte Crayon (1985) | Image Size: 25”h x 20”w; Framed Size: 34 ½”h x 28 ½”wdrawing

This untitled conte crayon portrait of an American Indian elder highlights William “Bill” Ahrendt’s talent in depicting the essence of his subject’s character and humanity. Pride, dignity, and a lifetime of experience are etched into the man’s face. With a seemingly simple study, the artist is able to engage the viewer to ponder the details of the subject’s life and experiences.

Hair held great symbolic importance for men in many tribes, especially in Western tribes like the Lakota and Blackfoot. Men in these tribes only cut their hair to show grief or shame, and often wore the front part of their hair in special styles including pompadours (hair stiffened with grease or clay so that it stands up), forelocks (one long strand of hair hanging down between the eyes), or small braids or topknots arranged in various shapes.

Source: First-Americans.com/6 Truths to Understand the Sacred Meaning of Hair for Native Americans

Oil on Board (1984) | Image Size: 9h x 12w; Framed Size: 16”h x 18 ¾”w

Oil on Board (1984) | Image Size: 9h x 12w; Framed Size: 16”h x 18 ¾”wWilliam Moyers had first-hand knowledge of working ranch horses having spent much of his teenage years as a cowhand on a Colorado ranch. After becoming a professional artist, he often called upon that knowledge to create realistic and authentic scenes such as this one. Here, two horses, fully saddled and equipped for range work, stand beside a wood rail fence patiently waiting for their riders to return. For the ponies, and the cowboys who will ride them, this scene in Colorado or the New Mexico high country, is simply a brief respite before their work continues. Moyers effectively contrasts the colors of the ponies, one dark and one white, to focus the viewer’s attention on the center of the painting. In the far background, he shows distant mountains that add to the sense of authenticity in the landscape.

An early member of the Cowboy Artists of America, William Moyers excelled as both a painter and sculptor. Born in Atlanta, he moved to Colorado as a teenager and that work paid for his education at Adams State College in Alamosa, Colorado. After graduation, he studied at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles and then worked in the animation department at Walt Disney Studios. Following his service during World War II, he and his wife moved to New York and then back to his hometown of Atlanta where he pursued a successful career as an illustrator of western subjects. By the early 1960’s he moved away from the illustration business to concentrate on his own art work. His career as a western artist spanned a half century and his work can be found in the many museums as well as private collections. Moyers won several awards in both sculpting and painting at the annual exhibitions and sales of the Cowboy Artists of America and served as that organization’s president on three occasions.

Waiting

Artist: William "Bill" Ahrendt (b. 1933)

William Moyers had first-hand knowledge of working ranch horses having spent much of his teenage years as a cowhand on a Colorado ranch. After becoming a professional artist, he often called upon that knowledge to create realistic and authentic scenes such as this one. Here, two horses, fully saddled and equipped for range work, stand beside a wood rail fence patiently waiting for their riders to return. For the ponies, and the cowboys who will ride them, this scene in Colorado or the New Mexico high country, is simply a brief respite before their work continues. Moyers effectively contrasts the colors of the ponies, one dark and one white, to focus the viewer’s attention on the center of the painting. In the far background, he shows distant mountains that add to the sense of authenticity in the landscape.

An early member of the Cowboy Artists of America, William Moyers excelled as both a painter and sculptor. Born in Atlanta, he moved to Colorado as a teenager and that work paid for his education at Adams State College in Alamosa, Colorado. After graduation, he studied at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles and then worked in the animation department at Walt Disney Studios. Following his service during World War II, he and his wife moved to New York and then back to his hometown of Atlanta where he pursued a successful career as an illustrator of western subjects. By the early 1960’s he moved away from the illustration business to concentrate on his own art work. His career as a western artist spanned a half century and his work can be found in the many museums as well as private collections. Moyers won several awards in both sculpting and painting at the annual exhibitions and sales of the Cowboy Artists of America and served as that organization’s president on three occasions.

Conte Crayon (1985) | Image Size: 25”h x 20”w; Framed Size: 34 ½”h x 28 5/8”w

Conte Crayon (1985) | Image Size: 25”h x 20”w; Framed Size: 34 ½”h x 28 5/8”wLittle Robe (Ski-o-mah), Southern Cheyenne, was born in about 1828, became a noted young warrior during combat against traditional enemies. His first tribal distinction came after a battle with Pawnee in Kansas in 1852, when he was given the honor of carrying from camp to camp the pipe of mourning in memory of those lost in the engagement. He became a chief around 1863. Colonel John Chivington, 3rd Colorado Volunteer Cavalry, claimed to have killed Little Robe at Sand Creek, Colorado, but reports of his death were greatly exaggerated.

The massacre compelled Little Robe to wage war against whites, but he soon came to the conclusion that such actions were hopeless. He participated in the April 1867 council with General Winfield S. Hancock at Fort Larned, Kansas, and then worked with Chief Black Kettle in an effort to persuade militant brethren to join them in signing the Medicine Lodge Treaty in October 1867.

In November 1868, Little Robe accompanied Black Kettle and other chiefs to Fort Cobb, Indian Territory, to talk peace with Colonel William Hazen, but were told that they had to make peace with General Phillip Sheridan to ensure their safety as he was in the field. The chiefs returned to their camp on the Washita River, and discussed what was said with their tribal council. When Black Kettle was killed during the attack by the 7th U.S. Cavalry, Little Robe initially supported the hostiles. In March 1869, he was camped at Sweetwater Creek, Texas, and met with Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer, who was attempting to secure the release of two captive white women from a nearby village. Later that spring, Little Robe surrendered at Fort Cobb, and assumed the role of principle chief of the peace faction.

Chief Little Robe was a member of delegations that toured Washington, D.C., and other eastern cities both in 1871 and 1873. He met President U.S. Grant on the second trip. He once again was a voice for peace during the Red River War of 1874-75, refusing to leave his reservation home in the Indian Territory on the North Canadian River. Although he was a proponent of peace with whites, he would not send children from his tribe to white schools. Little Robe (Ski-o-mah) died peacefully in 1886. (Ref. National Park Service, Washita Battlefield, National Historic Site, OK)

Bill Ahrendt’s skill in capturing the personality of Little Robe is fully evident in this portrait. While paying attention to details of clothing and hair style, Arhendt also focused on Little Robe’s face; the furrowed brow and lines around his eyes reveal both his character and reflect a lifetime of experiences.

Little Robe

Artist: William "Bill" Ahrendt (b. 1933)

Little Robe (Ski-o-mah), Southern Cheyenne, was born in about 1828, became a noted young warrior during combat against traditional enemies. His first tribal distinction came after a battle with Pawnee in Kansas in 1852, when he was given the honor of carrying from camp to camp the pipe of mourning in memory of those lost in the engagement. He became a chief around 1863. Colonel John Chivington, 3rd Colorado Volunteer Cavalry, claimed to have killed Little Robe at Sand Creek, Colorado, but reports of his death were greatly exaggerated.

The massacre compelled Little Robe to wage war against whites, but he soon came to the conclusion that such actions were hopeless. He participated in the April 1867 council with General Winfield S. Hancock at Fort Larned, Kansas, and then worked with Chief Black Kettle in an effort to persuade militant brethren to join them in signing the Medicine Lodge Treaty in October 1867.

In November 1868, Little Robe accompanied Black Kettle and other chiefs to Fort Cobb, Indian Territory, to talk peace with Colonel William Hazen, but were told that they had to make peace with General Phillip Sheridan to ensure their safety as he was in the field. The chiefs returned to their camp on the Washita River, and discussed what was said with their tribal council. When Black Kettle was killed during the attack by the 7th U.S. Cavalry, Little Robe initially supported the hostiles. In March 1869, he was camped at Sweetwater Creek, Texas, and met with Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer, who was attempting to secure the release of two captive white women from a nearby village. Later that spring, Little Robe surrendered at Fort Cobb, and assumed the role of principle chief of the peace faction.

Chief Little Robe was a member of delegations that toured Washington, D.C., and other eastern cities both in 1871 and 1873. He met President U.S. Grant on the second trip. He once again was a voice for peace during the Red River War of 1874-75, refusing to leave his reservation home in the Indian Territory on the North Canadian River. Although he was a proponent of peace with whites, he would not send children from his tribe to white schools. Little Robe (Ski-o-mah) died peacefully in 1886. (Ref. National Park Service, Washita Battlefield, National Historic Site, OK)

Bill Ahrendt’s skill in capturing the personality of Little Robe is fully evident in this portrait. While paying attention to details of clothing and hair style, Arhendt also focused on Little Robe’s face; the furrowed brow and lines around his eyes reveal both his character and reflect a lifetime of experiences.

Conte Crayon (1985) | Image Size: 25”h x 20”w; Framed Size: 34 ½”h x 28 ½”w

Conte Crayon (1985) | Image Size: 25”h x 20”w; Framed Size: 34 ½”h x 28 ½”w This untitled conte crayon portrait of an American Indian elder highlights William “Bill” Ahrendt’s talent in depicting the essence of his subject’s character and humanity. Pride, dignity, and a lifetime of experience are etched into the man’s face. With a seemingly simple study, the artist is able to engage the viewer to ponder the details of the subject’s life and experiences.

Hair held great symbolic importance for men in many tribes, especially in Western tribes like the Lakota and Blackfoot. Men in these tribes only cut their hair to show grief or shame, and often wore the front part of their hair in special styles including pompadours (hair stiffened with grease or clay so that it stands up), forelocks (one long strand of hair hanging down between the eyes), or small braids or topknots arranged in various shapes.

Source: First-Americans.com/6 Truths to Understand the Sacred Meaning of Hair for Native Americans

Unknown Title

Artist: William "Bill" Ahrendt (b. 1933)

This untitled conte crayon portrait of an American Indian elder highlights William “Bill” Ahrendt’s talent in depicting the essence of his subject’s character and humanity. Pride, dignity, and a lifetime of experience are etched into the man’s face. With a seemingly simple study, the artist is able to engage the viewer to ponder the details of the subject’s life and experiences.

Hair held great symbolic importance for men in many tribes, especially in Western tribes like the Lakota and Blackfoot. Men in these tribes only cut their hair to show grief or shame, and often wore the front part of their hair in special styles including pompadours (hair stiffened with grease or clay so that it stands up), forelocks (one long strand of hair hanging down between the eyes), or small braids or topknots arranged in various shapes.

Source: First-Americans.com/6 Truths to Understand the Sacred Meaning of Hair for Native Americans