Charlie Dye, CA Founding Member

(1906–1973)

Born in Colorado and raised in the West, Charlie Dye became a painter of western genre inspired by the work of Charles Russell. A founding members of the Cowboy Artists of America in 1965, he remained a member until his death.

As a child, Charlie spent as much time as he could on the range of the family ranch. He learned the ways of horses and cattle, and helped drive cattle. The cowboys captured his attention and admiration. For a few years he worked in movies riding his horse Old Navajo and spent his down time sketching. His pencil and paper became his escape. It wasn’t until years later when a horse fell on him that he considered art as a career. While recovering in the hospital, an old cowman in the next bed showed him a book of Charles Russell’s drawings.

At the age of 21, Dye attended both the Chicago Art Institute and the American Academy of Art. After a year and a half, he got his first professional job as an artist, designing egg cartons. At night, he studied drawing and painting. Dye married his wife Mary in 1929, a marriage that lasted until his death. He continued to study art with Harvey Dunn and Felix Schmidt, who became his mentor.

In 1936, Dye moved to New York City where he became a very successful illustrator working for magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post, Argosy, American Weekly and Outdoor Life. He used his son Steve in many of his illustrations. Following a 1957 California trip, Dye returned to Colorado and became a partner at the Colorado Institute of Art. While teaching, his paintings were exhibited and sold at galleries in New Mexico and Arizona.

Once his work became more widely accepted, Dye gave up teaching and illustrating and relocated to Sedona, Arizona. There he met Joe Beeler, John Hampton and George Phippen; all founding members of the eponymous Cowboy Artists of America. He was more proud of being a founder than any of his other achievements. He was considered outspoken, opinionated and a very loyal friend, especially to fellow artists of the CAA. In 1967, Dye won the first gold medal for his oil painting “Through the Aspens,” which is now part of the permanent collection at the Cowboy Hall of Fame.

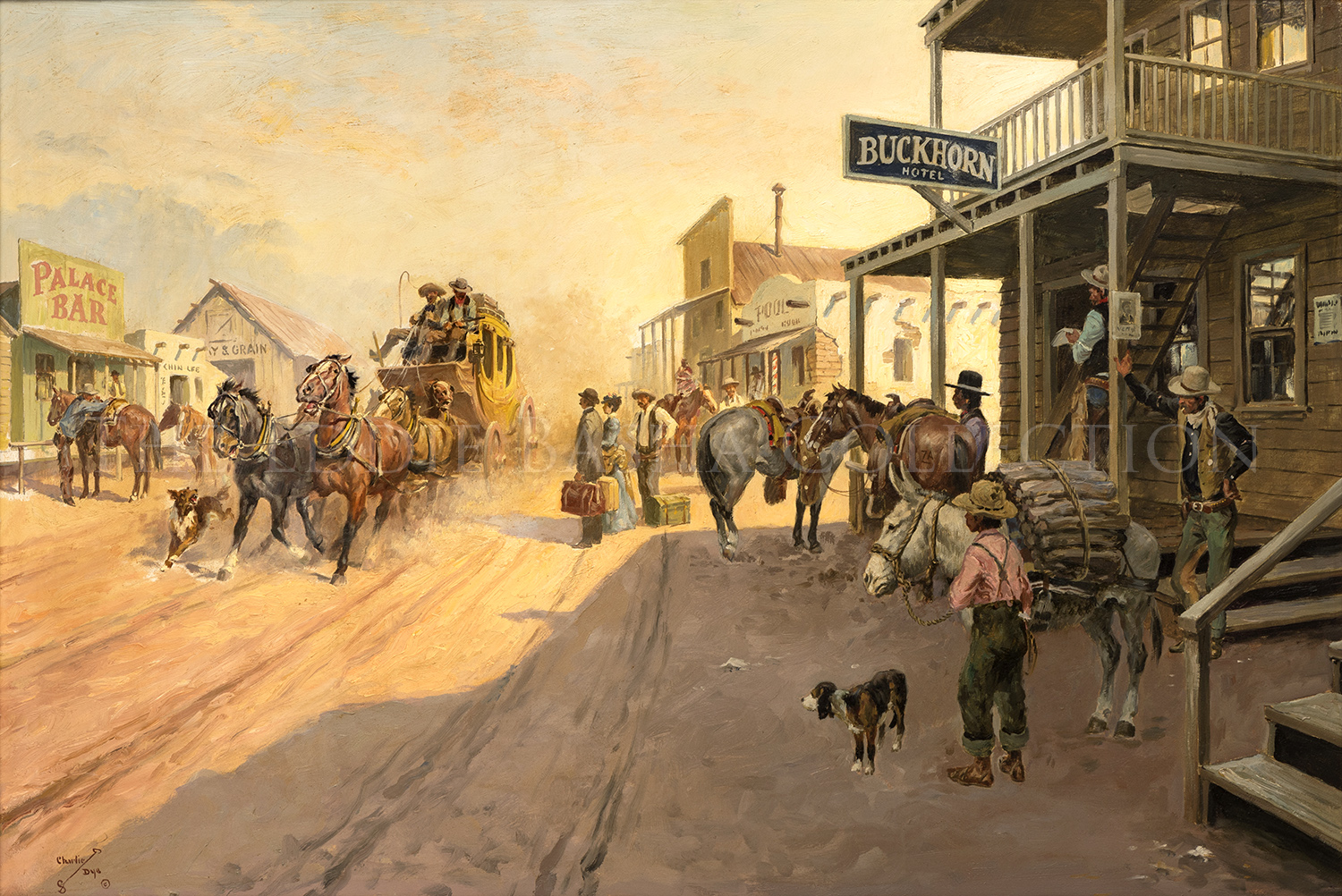

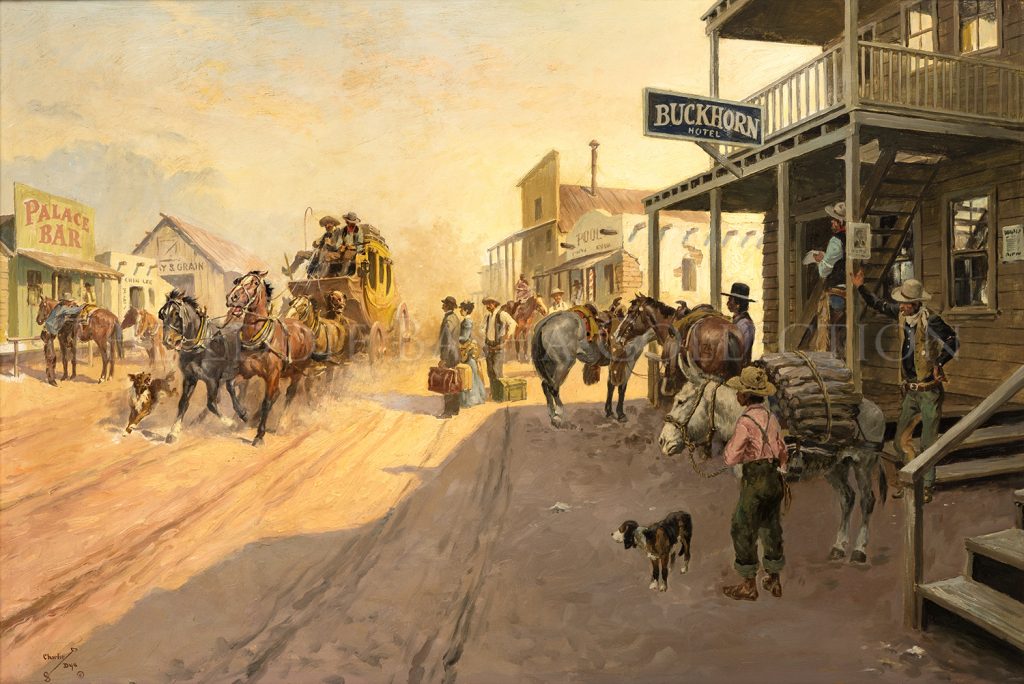

The Butterfield Stage

Artist: Charlie Dye, CA Founding Member (1906–1973)

Description: Oil (1963) | Image Size: 24”h x 36”w; Framed Size: 34”h x 46”wpainting

Whether for driver, passenger or town folk, the arrival of a stagecoach was greatly anticipated! Rolling into a town meant much-needed respite (and relative safety) for the weary travelers, plus water and rest for the horses. From the perspective of the citizenry, it meant greenback-paying customers for local businesses, the arrival of a loved one, or maybe the delivery of a letter from one. Each and every stage carried with it the stories of those whose lives were impacted by its very existence.

Connectivity and communication between the East and West was finally realized in 1857 when John Butterfield and his business associates’ bid was accepted by the U.S. Post Office. Though railroad bids had been submitted, a more immediate resolution was needed and the Butterfield Overland Mail Trail connecting St. Louis and Memphis with San Francisco served that purpose. And though the service only operated from 1858 through 1861, it was the essential rough-and-rugged precursor that aided in the transformation of communication, transportation and growth.

An image of this original oil painting is depicted on page 103 in the book entitled Charlie Dye – One helluva western painter, authored by Paul E. Weaver, forward written by Joe Beeler, and published by Petersen Prints in Los Angeles 1981.

Meat for the Outfit

Artist: Charlie Dye, CA Founding Member (1906–1973)

Description: Oil (1965) | Image Size: 20”h x 30”w; Framed Size: 29”h x 38”wpainting

A founding member of the Cowboy Artists of America, Charlie Dye, evokes a cold winter day in this painting of a cowhand making his way out of the forest across a snow-covered ground toward a ranch in the distance. The cowboy is dressed to withstand the frigid temperatures of a winter’s day that is nearing sundown and has had a successful hunt with two stags strapped to his pack horse. Foreboding dark gray clouds hover over the ranch buildings and are an effective contrast to the cool sunlight on the snow.

A great admirer of the work of Charles M. Russell, it is possible that Dye alluded to the fact that before becoming a night wrangler, Russell hunted game for cow outfits in Montana.

Cheyenne Sundown

Artist: Charlie Dye, CA Founding Member (1906–1973)

Description: Oil (1969) | Image Size: 30”h x 48”w; Framed Size: 39”h x 57”wpainting

This large painting of a group of Cheyenne Indians riding across a barren plain has both narrative and a metaphoric quality. In simple narrative terms, the Indians are moving camp and are shown nearing the end of a long journey. They are scattered across the canvas, riding from right to left. One warrior is shown astride a white horse and is spotlighted by a bright ray of sunlight just as he is about to cross into a deep shadow. Other riders are shown to his right and left and far behind him.

In a metaphoric sense, Dye painted an image that suggests an end to the way of life on the open prairie that persisted for generations. The Cheyenne are literally riding out of the sunlight and symbolically away from that prior lifestyle. It is a powerful statement and a very evocative painting, made more so by Dye’s composition and clever use of light and shadow.

Charlie Dye attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the American Academy of Art. He illustrated for The Saturday Evening Post, Outdoor Life, Argosy, and American Weekly magazines. When he returned to his Colorado roots, he taught at the Colorado Institute of Art. As a founding member of the Cowboy Artists of America, he was an outspoken advocate for the genre as well as the organization, a loyal colleague and a trusted friend. He received numerous honors, awards, and accolades throughout his career.

Long Road to Town

Artist: Charlie Dye, CA Founding Member (1906–1973)

Description: Oil (1968) | Image Size: 24”h x 48”w; Framed Size: 33.5”h x 57”wpainting

In this scene of the historic West, authentically dressed cowboys accompany a wagon across a dusty and parched landscape on its way into a frontier town most likely to pick up provisions. As he often did, Charlie Dye used yellows, browns, and dull greens to convey the sense of an arid environment. The group is riding across a barren expanse of prairie following a rutted wagon trail. The slow movement of the riders and the wagon is accentuated by the small cloud of dust kicked up by the wagon wheel. Dye gives the viewer a sense of distance by placing a mesa in the background.

Like his hero, Charles M. Russell, Charlie Dye worked as a cowboy before turning to a career in art. In fact, Dye was a top hand on several Colorado ranches prior to moving to Chicago to study art and subsequently working as an illustrator in New York City. He brought an authenticity of experience to his painting of cowboys that few artists can match.

Rawhide Rhapsody

Artist: Charlie Dye, CA Founding Member (1906–1973)

Description: Oil (1969) | Image Size: 24”h x 32”w; Framed Size: 33”h x 41”wpainting

Oil (1963) | Image Size: 24”h x 36”w; Framed Size: 34”h x 46”w

Oil (1963) | Image Size: 24”h x 36”w; Framed Size: 34”h x 46”wWhether for driver, passenger or town folk, the arrival of a stagecoach was greatly anticipated! Rolling into a town meant much-needed respite (and relative safety) for the weary travelers, plus water and rest for the horses. From the perspective of the citizenry, it meant greenback-paying customers for local businesses, the arrival of a loved one, or maybe the delivery of a letter from one. Each and every stage carried with it the stories of those whose lives were impacted by its very existence.

Connectivity and communication between the East and West was finally realized in 1857 when John Butterfield and his business associates’ bid was accepted by the U.S. Post Office. Though railroad bids had been submitted, a more immediate resolution was needed and the Butterfield Overland Mail Trail connecting St. Louis and Memphis with San Francisco served that purpose. And though the service only operated from 1858 through 1861, it was the essential rough-and-rugged precursor that aided in the transformation of communication, transportation and growth.

An image of this original oil painting is depicted on page 103 in the book entitled Charlie Dye – One helluva western painter, authored by Paul E. Weaver, forward written by Joe Beeler, and published by Petersen Prints in Los Angeles 1981.

The Butterfield Stage

Artist: Charlie Dye, CA Founding Member (1906–1973)

Whether for driver, passenger or town folk, the arrival of a stagecoach was greatly anticipated! Rolling into a town meant much-needed respite (and relative safety) for the weary travelers, plus water and rest for the horses. From the perspective of the citizenry, it meant greenback-paying customers for local businesses, the arrival of a loved one, or maybe the delivery of a letter from one. Each and every stage carried with it the stories of those whose lives were impacted by its very existence.

Connectivity and communication between the East and West was finally realized in 1857 when John Butterfield and his business associates’ bid was accepted by the U.S. Post Office. Though railroad bids had been submitted, a more immediate resolution was needed and the Butterfield Overland Mail Trail connecting St. Louis and Memphis with San Francisco served that purpose. And though the service only operated from 1858 through 1861, it was the essential rough-and-rugged precursor that aided in the transformation of communication, transportation and growth.

An image of this original oil painting is depicted on page 103 in the book entitled Charlie Dye – One helluva western painter, authored by Paul E. Weaver, forward written by Joe Beeler, and published by Petersen Prints in Los Angeles 1981.

Oil (1965) | Image Size: 20”h x 30”w; Framed Size: 29”h x 38”w

Oil (1965) | Image Size: 20”h x 30”w; Framed Size: 29”h x 38”wA founding member of the Cowboy Artists of America, Charlie Dye, evokes a cold winter day in this painting of a cowhand making his way out of the forest across a snow-covered ground toward a ranch in the distance. The cowboy is dressed to withstand the frigid temperatures of a winter’s day that is nearing sundown and has had a successful hunt with two stags strapped to his pack horse. Foreboding dark gray clouds hover over the ranch buildings and are an effective contrast to the cool sunlight on the snow.

A great admirer of the work of Charles M. Russell, it is possible that Dye alluded to the fact that before becoming a night wrangler, Russell hunted game for cow outfits in Montana.

Meat for the Outfit

Artist: Charlie Dye, CA Founding Member (1906–1973)

A founding member of the Cowboy Artists of America, Charlie Dye, evokes a cold winter day in this painting of a cowhand making his way out of the forest across a snow-covered ground toward a ranch in the distance. The cowboy is dressed to withstand the frigid temperatures of a winter’s day that is nearing sundown and has had a successful hunt with two stags strapped to his pack horse. Foreboding dark gray clouds hover over the ranch buildings and are an effective contrast to the cool sunlight on the snow.

A great admirer of the work of Charles M. Russell, it is possible that Dye alluded to the fact that before becoming a night wrangler, Russell hunted game for cow outfits in Montana.

Oil (1969) | Image Size: 30”h x 48”w; Framed Size: 39”h x 57”w

Oil (1969) | Image Size: 30”h x 48”w; Framed Size: 39”h x 57”wThis large painting of a group of Cheyenne Indians riding across a barren plain has both narrative and a metaphoric quality. In simple narrative terms, the Indians are moving camp and are shown nearing the end of a long journey. They are scattered across the canvas, riding from right to left. One warrior is shown astride a white horse and is spotlighted by a bright ray of sunlight just as he is about to cross into a deep shadow. Other riders are shown to his right and left and far behind him.

In a metaphoric sense, Dye painted an image that suggests an end to the way of life on the open prairie that persisted for generations. The Cheyenne are literally riding out of the sunlight and symbolically away from that prior lifestyle. It is a powerful statement and a very evocative painting, made more so by Dye’s composition and clever use of light and shadow.

Charlie Dye attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the American Academy of Art. He illustrated for The Saturday Evening Post, Outdoor Life, Argosy, and American Weekly magazines. When he returned to his Colorado roots, he taught at the Colorado Institute of Art. As a founding member of the Cowboy Artists of America, he was an outspoken advocate for the genre as well as the organization, a loyal colleague and a trusted friend. He received numerous honors, awards, and accolades throughout his career.

Cheyenne Sundown

Artist: Charlie Dye, CA Founding Member (1906–1973)

This large painting of a group of Cheyenne Indians riding across a barren plain has both narrative and a metaphoric quality. In simple narrative terms, the Indians are moving camp and are shown nearing the end of a long journey. They are scattered across the canvas, riding from right to left. One warrior is shown astride a white horse and is spotlighted by a bright ray of sunlight just as he is about to cross into a deep shadow. Other riders are shown to his right and left and far behind him.

In a metaphoric sense, Dye painted an image that suggests an end to the way of life on the open prairie that persisted for generations. The Cheyenne are literally riding out of the sunlight and symbolically away from that prior lifestyle. It is a powerful statement and a very evocative painting, made more so by Dye’s composition and clever use of light and shadow.

Charlie Dye attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the American Academy of Art. He illustrated for The Saturday Evening Post, Outdoor Life, Argosy, and American Weekly magazines. When he returned to his Colorado roots, he taught at the Colorado Institute of Art. As a founding member of the Cowboy Artists of America, he was an outspoken advocate for the genre as well as the organization, a loyal colleague and a trusted friend. He received numerous honors, awards, and accolades throughout his career.

Oil (1968) | Image Size: 24”h x 48”w; Framed Size: 33.5”h x 57”w

Oil (1968) | Image Size: 24”h x 48”w; Framed Size: 33.5”h x 57”wIn this scene of the historic West, authentically dressed cowboys accompany a wagon across a dusty and parched landscape on its way into a frontier town most likely to pick up provisions. As he often did, Charlie Dye used yellows, browns, and dull greens to convey the sense of an arid environment. The group is riding across a barren expanse of prairie following a rutted wagon trail. The slow movement of the riders and the wagon is accentuated by the small cloud of dust kicked up by the wagon wheel. Dye gives the viewer a sense of distance by placing a mesa in the background.

Like his hero, Charles M. Russell, Charlie Dye worked as a cowboy before turning to a career in art. In fact, Dye was a top hand on several Colorado ranches prior to moving to Chicago to study art and subsequently working as an illustrator in New York City. He brought an authenticity of experience to his painting of cowboys that few artists can match.

Long Road to Town

Artist: Charlie Dye, CA Founding Member (1906–1973)

In this scene of the historic West, authentically dressed cowboys accompany a wagon across a dusty and parched landscape on its way into a frontier town most likely to pick up provisions. As he often did, Charlie Dye used yellows, browns, and dull greens to convey the sense of an arid environment. The group is riding across a barren expanse of prairie following a rutted wagon trail. The slow movement of the riders and the wagon is accentuated by the small cloud of dust kicked up by the wagon wheel. Dye gives the viewer a sense of distance by placing a mesa in the background.

Like his hero, Charles M. Russell, Charlie Dye worked as a cowboy before turning to a career in art. In fact, Dye was a top hand on several Colorado ranches prior to moving to Chicago to study art and subsequently working as an illustrator in New York City. He brought an authenticity of experience to his painting of cowboys that few artists can match.