John Ford Clymer, CA

(1907-1989)

During his long artistic career, John Clymer developed a highly effective process for painting the history of the American West. First, he and his wife, Doris, would painstakingly research the subject of the painting, down to the smallest details of setting, climate, and historic period. After completing their research, they would then travel to the proposed site for the painting to get a firsthand feeling for the area. As a result of these intensive preparations, Clymer’s paintings are both rich in accurate historical detail and successful in capturing the essence of their geographical settings. Clymer was adept at recreating an historical event or era while, at the same time, drawing the viewer into the physical scene.

Clymer was born in Ellensburg, Washington, in 1907. By the time he joined the Cowboy Artists of America in 1969, he had achieved a highly successful career as both an illustrator and easel painter. Through his work for the Saturday Evening Post, he brought images of the West to literally thousands of Americans. From 1942 to 1962, Clymer painted more than seventy cover illustrations for the magazine, many of them Western scenes. In the era before television, Clymer’s illustrations served to introduce countless people to the many stories of the American West, from the fur trade to the cattle drives. He literally bridged two generations of Western artists – the early twentieth century illustrators such as Harvey Dunn, with whom he studied, to the members of the CAA, for whom he served as mentor and role model.

Clymer was particularly interested in depicting the history of the Pacific Northwest, where he grew up. He attempted to tell the whole story of the region, creating sensitive and detailed depictions of Native American life and the meeting of Native and Anglo cultures. One of his featured subjects was the great fur trade era, which led to the exploration of the region. Clymer was also equally talented in depicting the native wildlife of the Pacific Northwest. Fittingly, his life and work is now commemorated in the Clymer Museum in his native town of Ellensburg.

Source: Cowboy Artists of America

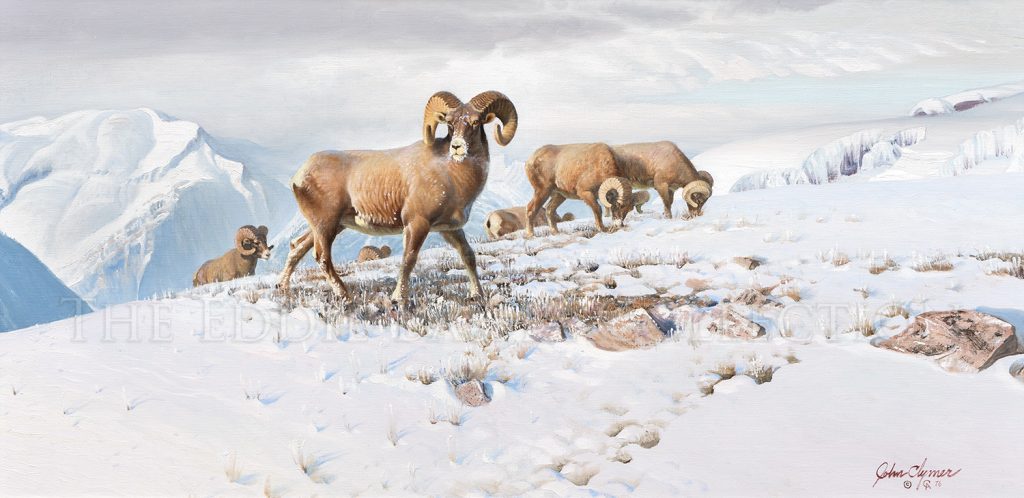

North Slope

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1975) | Image Size: 20”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 30”h x 50”wpainting

Judging by the number of paintings devoted to the subject, Cowboy Artists of America Member John Ford Clymer was obviously fascinated and had a deep appreciation for big horn sheep. He painted them in many different locales and at various times of the year, but he favored showing them in snow covered winter scenes usually high above the tree line in the Rocky Mountains. Choosing that format allowed him to realistically capture these animals in pristine and dramatic settings, such as the high snow-covered meadow of North Slope, depicted in the waning hours of sunlight at the end of the day.

In the painting, two sheep move across the canvas emerging from deep shadows to bright sunlight. The transition from dark to light adds a sense of movement to the scene. Distant mountains in the background along with several other sheep shown in the distance give a sense of grand scale to the landscape. As with many of his paintings, all elements seem to be in perfect balance—the land, the animals, the sky, all are part in equal measure of the natural world.

The Trapper's Tree

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1984) | Image Size: 30”h x 48”w; Framed Size: 41”h x 59”wpainting

Of all the hardy men who challenged the western wilderness of the early nineteenth century, none were more resourceful and tenacious than the free trappers. There was money to be made in trapping to be sure. But, it was something more than greed that drew these rugged men so far away from the comfort and convenience of settled America back east of the Mississippi.

Beaver pelts were a way to pay the bill for living out a grand adventure. Men alone in a strange and hard land tested their mettle to a degree more than city-dwelling wage earners would ever know. Out there, in the silence and isolation, a man came to grips with his essence. He gloried in his strengths and fought to overcome his weaknesses. This was no life for those of timid spirits.

In the dead of winter, snow lies in deep drifts across the land. Everything is white and the silence is overwhelming. Two men are drawn together by the scant warmth of a small fire and a shared feeling of intense loneliness. Few words are spoken. The men are within themselves, thing perhaps of homes and families thousands of miles away. Maybe they try to muster up memories of last years rendezvous when Indians and trappers came together to barter furs with the traders. Long summer days of noise and zest, and nights of wild tales and raw whiskey. But it all seems so long ago.

Now, they huddle near the fire and wait for the cooking pot to boil. Their earthly worth is represented by the fresh furs draped on the bare tree and the traps that hang there, or lay beneath the icy water of a nearby stream where the fox drinks and beaver builds his home.

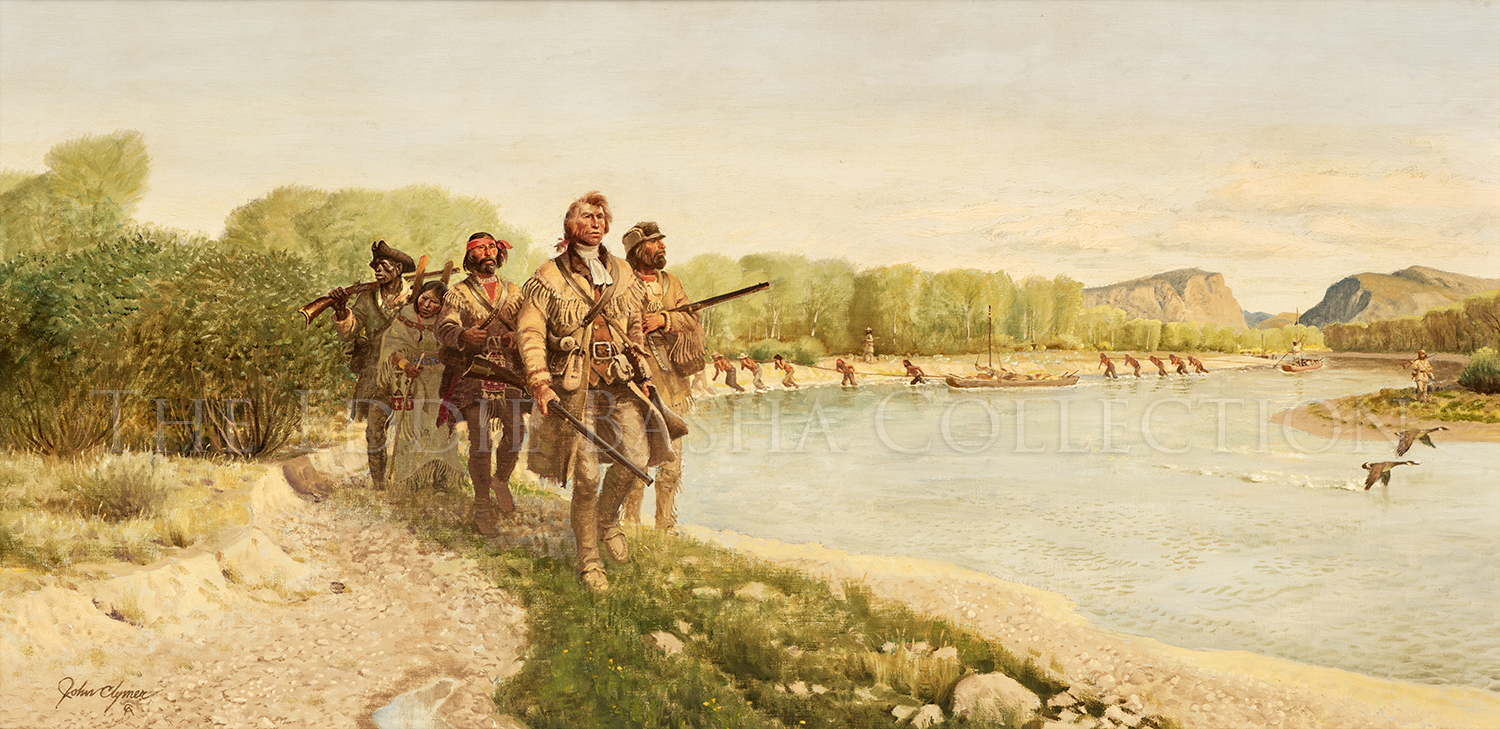

The Salt Makers – Lewis & Clark Expedition 1806

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1975) | Image Size: 24”h x 48”w; Framed Size: 34”h x 58”wpainting

When the Lewis and Clark party reached the mouth of the Columbia River, they decided to winter near the Pacific Ocean. They chose a spot on the south side of the Columbia, on a high point of land above a small river emptying into a small bay. There they built a fort and established their winter quarters which they called Fort Clatsop.

From the fort, they sent a party of men out to the coast for the purpose of setting up a camp and a salt-making operation. The camp was on the coast about fifteen miles southwest of Fort Clatsop near the lodges of some Killamuck and Clatsop Indians. There they found a place near a fresh stream of water running into the ocean and plenty of wood for fires. They built a stone cairn which would accommodate the five large kettles for boiling sea water. By keeping the kettles filled and the fires going day and night, they were able to obtain from three-quarters to a gallon of salt a day. On February 21, 1806, when they abandoned camp, they had about twenty gallons in all. They thought this would be sufficient to last them until they reached their caches on the Missouri River.

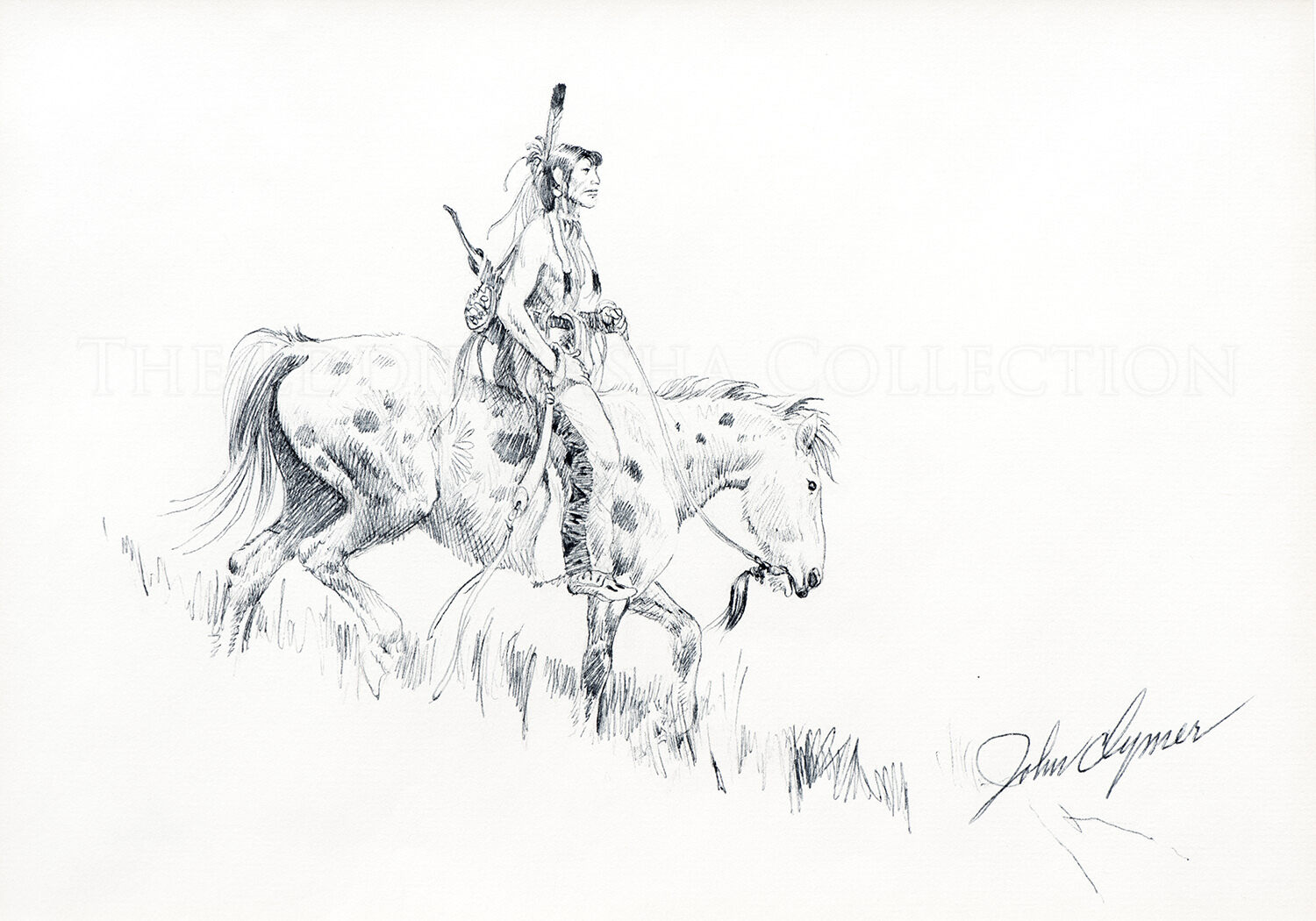

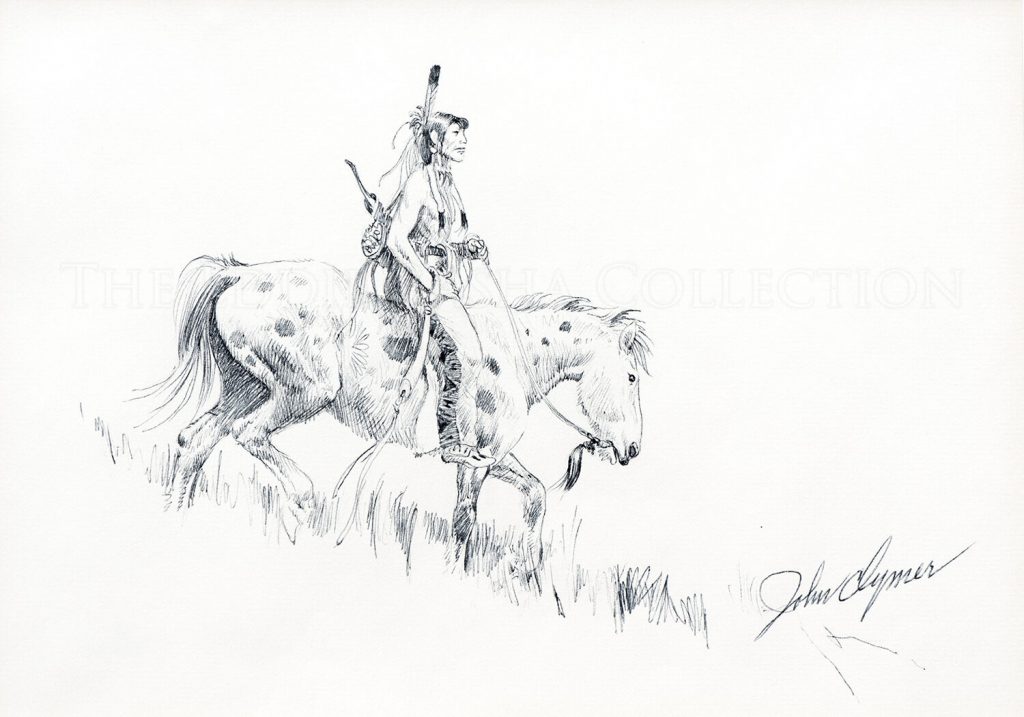

Unknown Title

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Pen & Ink | Image Size: 7”h x 10”w; Framed Size: 14 ¼”h x 17”wdrawing

This drawing stands alone as a finished work even though it may have been a study for one of John Ford Clymer’s larger works. His drawings varied greatly in terms of standing as finished, completed works, or studies and sketches to be employed later in other paintings. Either way, Clymer’s years of illustrative work served him well. Here, the figures of the Indian rider and horse are rendered skillfully, while the background is merely suggested.

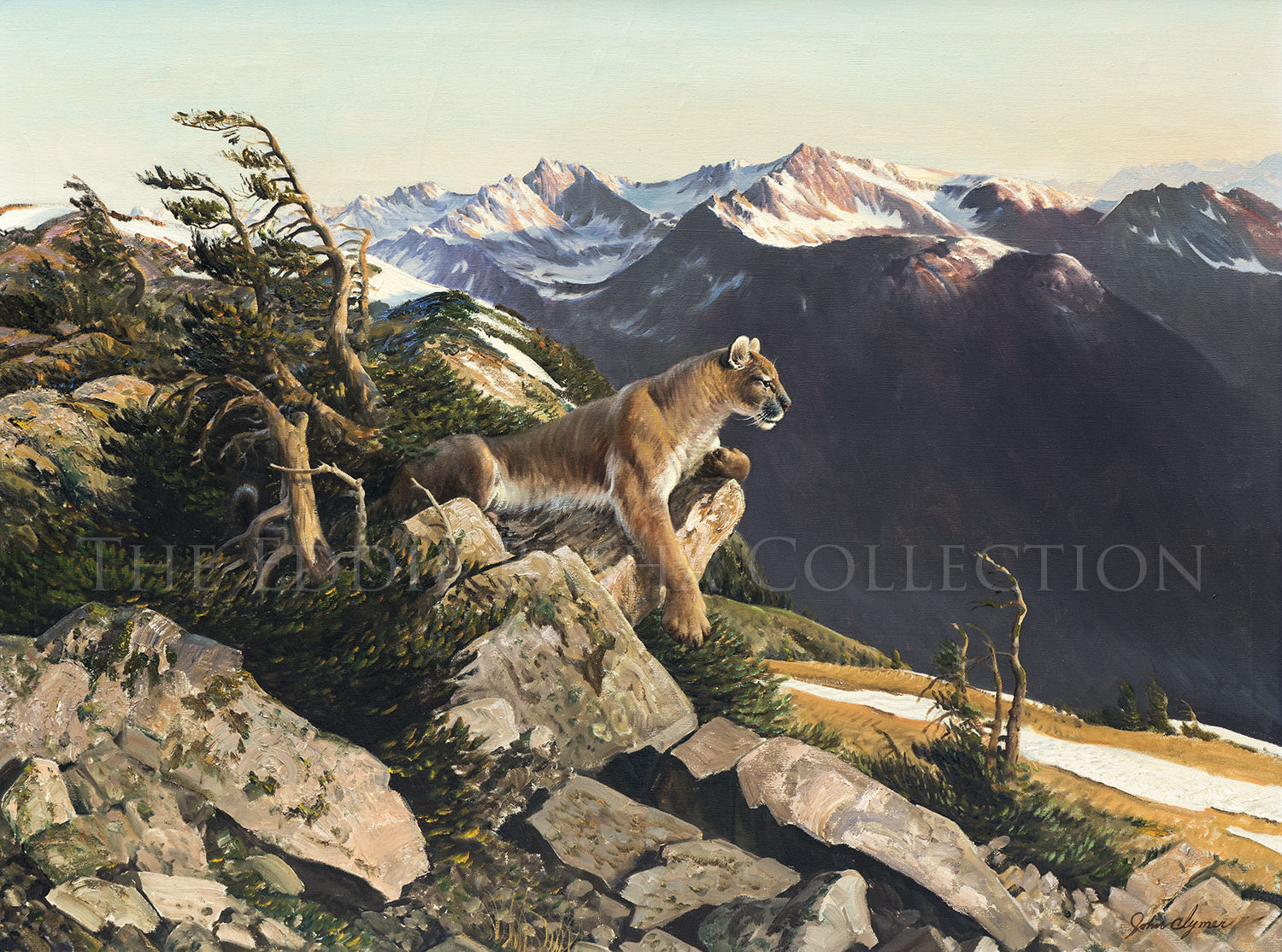

The Big Long Tail

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil | Image Size: 24”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 33”h x 49”wpainting

John Ford Clymer spent many years in and around the northern Rocky Mountains researching his historical paintings. In doing so, he also had the opportunity to observe the wildlife of the region and he often used cougars, big horn sheep, and bears, as the primary subjects of his paintings. He shows those animals, such as the cougar in “The Big Long Tail,” in their natural habitats. His compositions are intended to focus the viewer’s attention on the animal, much as the composition of his historical paintings is intended to keep the viewer’s eye on the heart of the story being told.

Here a cougar is visualized moving across a rocky and rough terrain with towering mountains and billowy white clouds behind him. Having placed the cougar between the ground and the background mountains, its figure is framed in the middle of the painting. The tan hide of the big cat is contrasted with the darkness of the mountains and the tans and greens of the landscape. That sharp contrast between colors and the positioning of the cougar, keeps the viewer’s attention focused on him. Per usual, Clymer’s skill at capturing the anatomy and personality of the wildlife subject creates a very evocative western landscape.

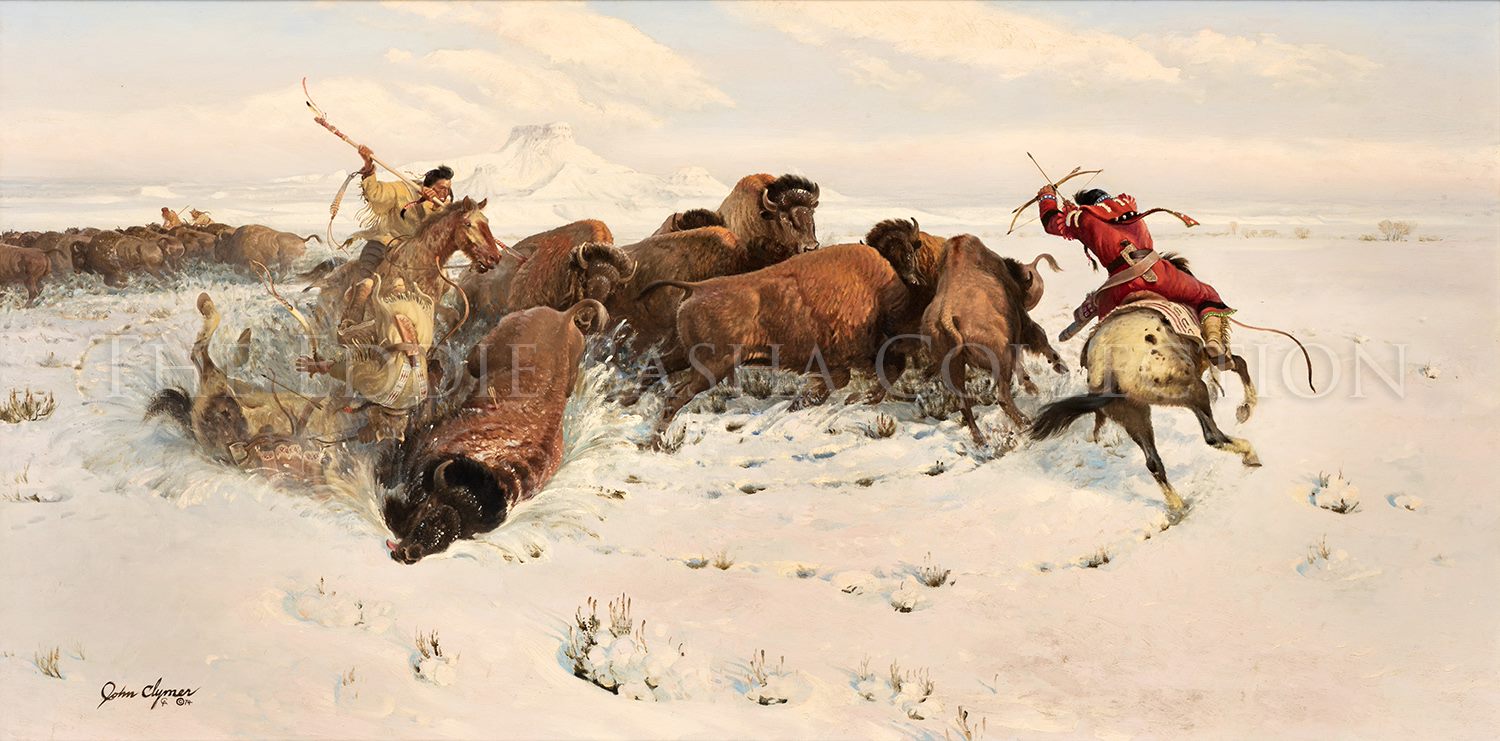

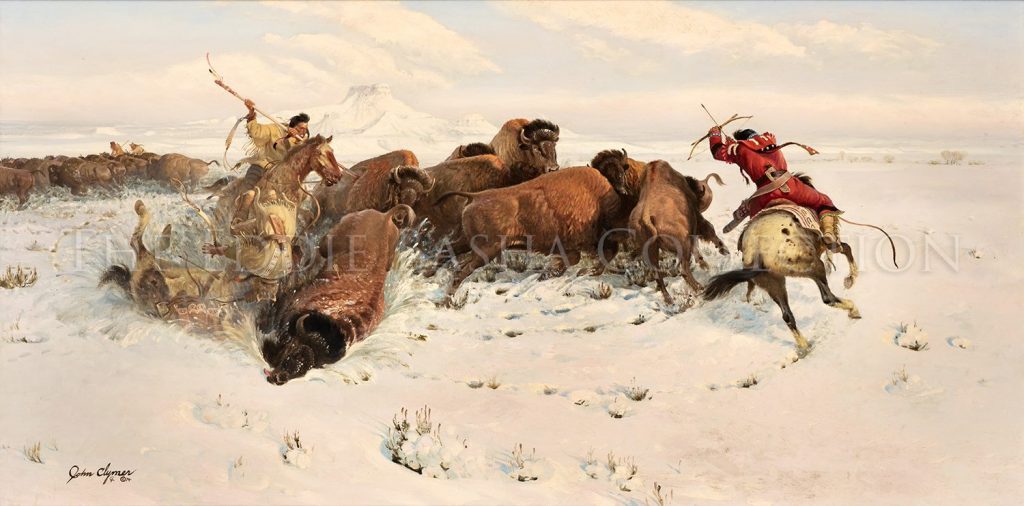

Hunt at Crowheart

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1974) | Image Size: 30”h x 60”w; Framed Size: 41”h x 70”wpainting

The buffalo was a fundamental element of Plains Indian life. It was a sacred, life-giving animal and the Indian paid tribute to its spirit before every hunt. The buffalo supplied more than meat; it was the source of an endless variety of essentials to Indian life. Clothing, shelter, weapons, tools, riding gear, ceremonial objects and many other things were obtained from the hide and bone of the buffalo.

This painting shows a party of Crow hunters who have begun to work a buffalo herd in the Wind River Valley of present day Wyoming. Three hunters have cut off a more efficient kill; it was an activity with the potential for danger at every moment. Here, a big bull, which could stand six feet at the hump and weigh up to a ton, has fallen, upsetting a hunter and his horse. The Indian to the left is using his lance to puncture the buffalo’s diaphragm and collapse its lung by hitting a spot just behind the last rib. The other Crow hunter is readying his short bow and iron-tipped arrow to do the same.

The hunter’s horse was of major importance in the success of the hunt and a Crow prized his buffalo horse above most all of his possessions, as did the other Indians of the Northern Plains. An indication of the regard in which the hunter held his buffalo horse is revealed in the fact that when horse thieves from other tribes were known to be in the area, a hunter often took his best horse into his teepee at night. On these occasions, the women were forced to sleep outside.

After the hunt, the women would follow with pack horses to skin and butcher the kills, and transport the hide and meat back to camp. It was a part of the hunting ritual to leave behind the hearts of the dead buffalo. The Plains Indian believed that the mystical powers of the hearts would help to regenerate the herd.

A photographed image of this piece is depicted in the book entitled “John Clymer – An Artist's Rendezvous with the Frontier West,” authored by Walt Reed and published by Northland Press in 1976. The original oil painting has been loaned on numerous occasions to multiple institutions throughout the years such as the Briscoe Western Art Museum, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, National Museum of Wildlife Art, Autry Museum of the American West, and The Thomas Gilcrease Museum.

Summer the High Country

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil | Image Size: 24”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 35“h x 51“wpainting

Light, shadow and contrasting colors are important elements in this scene of a mother grizzly bear and her two cubs making their way across rough ground and enjoying the cool water runoff in the high mountain meadow. The mother grizzly is positioned in the center of the painting, warily protecting her cubs. The foreground of the painting which contains the bear family is shown in dark shadow while the background is much lighter, particularly the lingering patches of snow which indicate the summer season. The bears are moving up a rocky incline. Their trajectory will take them across the viewer’s field of vision and out of the frame; the movement is from right to left, from light to shadow. The contrast of colors and textures adds another sense of realism to the scene.

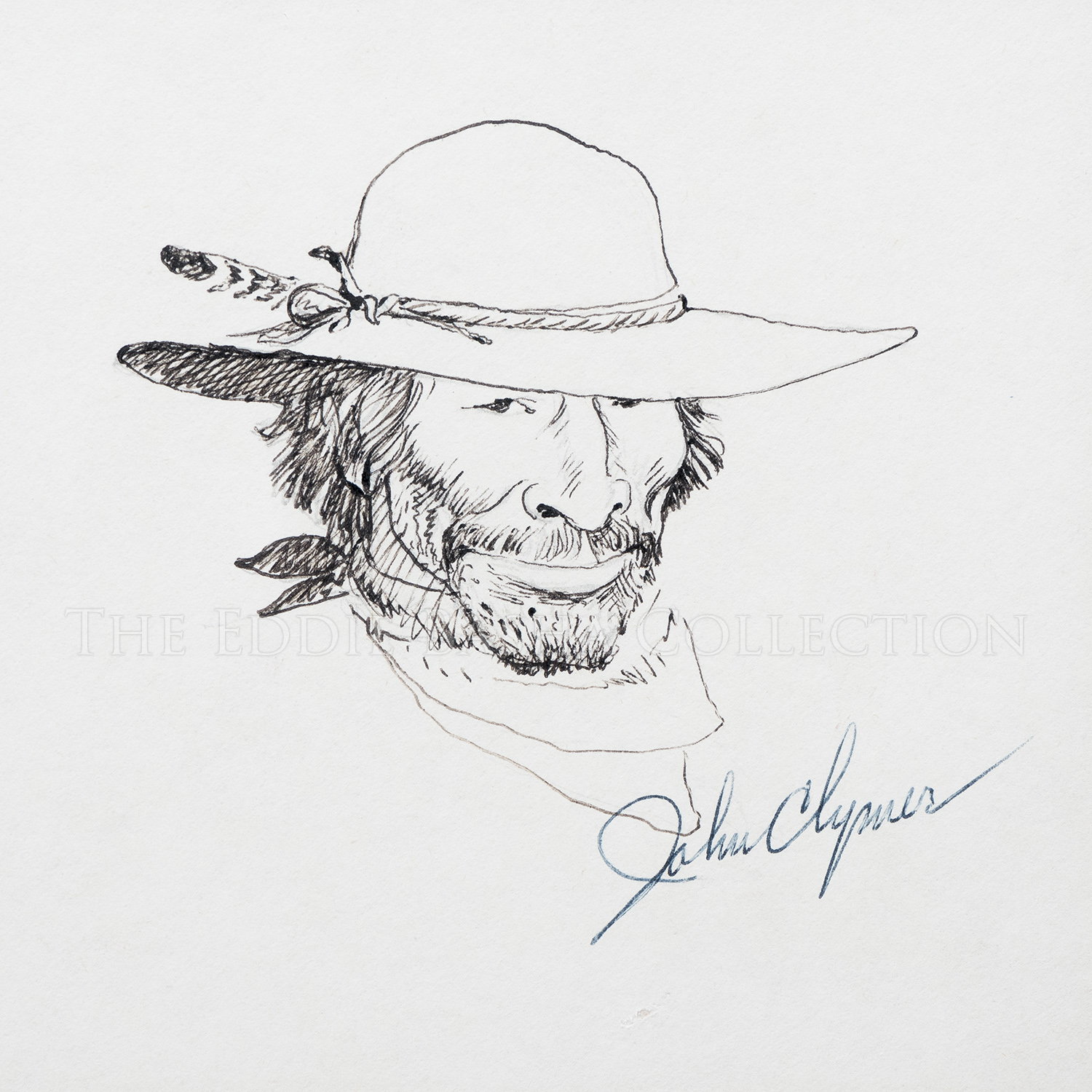

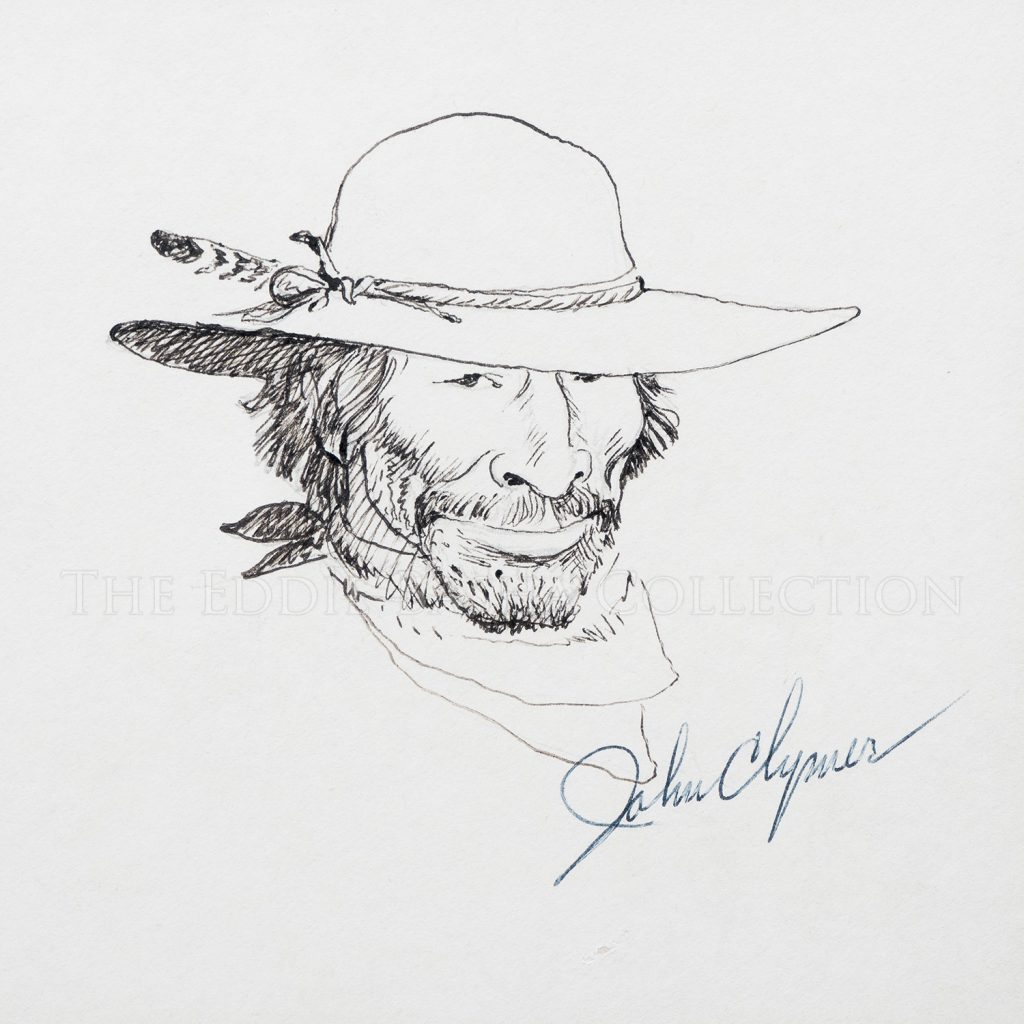

Unknown Title

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Pen & Ink | Image Size: 5”h x 5”w; Framed Size: 12 ¼”h x 12 ¼”wdrawing

Often the task of an artist is to quickly capture the essence or character of a particular subject. John Clymer’s oil paintings are most often populated with several unique individuals, all of whom seem separate and distinct from the other figures on the canvas. Drawing such realistic figures was one of Clymer’s true strengths and he practiced and perfected that technique while working as a commercial illustrator and as a professional fine artist through literally thousands of sketches, some of which, like this portrait of a mountain man, are quite small. And, even at such a small size, Clymer is adept at adding nuances and depth to the character he has drawn.

Frosty Morning

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1976) | Image Size: 20”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 30“h x 50“wpainting

“Frosty Morning,” an early wildlife painting by John Ford Clymer (1907-1989) illustrates his skill at capturing animals realistically in mid-motion and his talent as a landscape painter. Clymer conveys a sense of place and atmosphere in this setting. As the sheep climb up the peak, they are framed by the snow covered rocky terrain in front of them and the blue sky behind. And though the landscape is sparse, the viewer gets a true feel for the location.

Clymer, a member of the Cowboy Artists of America (1969-1989), received worldwide recognition for his body of work throughout his lifetime. In addition to the EBC Clymer exhibit of over 40 of his original oil paintings, did you know that the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, WY, exhibits Clymer’s studio and in Clymer’s birthplace of Ellensburg, WA, the Clymer Museum shares rare insight into his early years? And, just about every significant western art museum also exhibits one or more of Clymer’s stunning work as well from either his wildlife series or historically referenced oil paintings, or the many illustrations he created for some of the world’s largest magazine publications such as The Saturday Evening Post, Woman’s Day and Field & Stream Magazines.

Supply Column

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1985) | Image Size: 15”h x 30”w; Framed Size: 25”h x 40”wpainting

“Supply Column” made its debut at the 20th Annual Cowboy Artists of America Exhibition & Sale in 1985 at the Phoenix Art Museum. Together, Doris and John Clymer wrote the following narrative to accompany the painting.

Stories of a wild and wonderful country were brought back down the Missouri River in the early 1800’s along with bales of beaver pelts and other furs worth near their weight in gold. Grizzled, greasy men spoke of a fortune in furs there for the taking out where the wild prairies butted up against spectacular snow-capped mountains.

Yankee enterprise was quick to respond to the prospect of a profit. Expeditions started up the Missouri to establish company trading posts in a territory which had yet to be mapped in any significant detail and where real sovereignty still belonged to the Indian. Once the outposts were operating, trappers would no longer have to make the long journey back to St. Louis to sell their furs and obtain provisions. An even greater commercial potential existed if the Indian tribes could be induced to trade.

The scene here is a supply column which is on its way west from the main post at Fort Union to deliver trade goods and provision to the more distant outlying posts along the Missouri River breaks. The men are hard-bitten frontier types who have learned how to survive in an environment that can quickly turn harsh and hostile. Their long rifles keep meat in their bellies and hair on their heads. These were the men who relished the vitality of a life boiled down to the basics that took pride in self-reliance and considered danger to be like seasoning in the stew.

The fur trading era was a brief and dramatic episode in the pageant of the Old West. It gave European men a foothold in Indian country and blazed the trail for those who would follow.

Narrative Source: Doris and John Ford Clymer

Big Horn Sheep

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil | Image Size: 30”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 40”h x 50”wpainting

From the time Indian hunters first looked up from the forested lower slopes to behold these animals roaming the rugged upper reaches of the Rockies, the big horn sheep has inspired a sense of reverence and wonder in all who witnessed its uncannily accurate footing and sheer power in vaulting from one precipice to another. Fur trappers and explorers who ventured beyond the western boundary of the Great Plains were no less awed.

The bighorn is a survivor of the ages in its bitter, harsh, yet starkly beautiful surroundings. These creatures serve as a timeless, vivid representation of the primal tracts of our western wilderness where man’s presence remains a rarity. In the image here, the mountain sheep is portrayed with all its natural grace, strength and dignity in the rocky solitude that is its home.

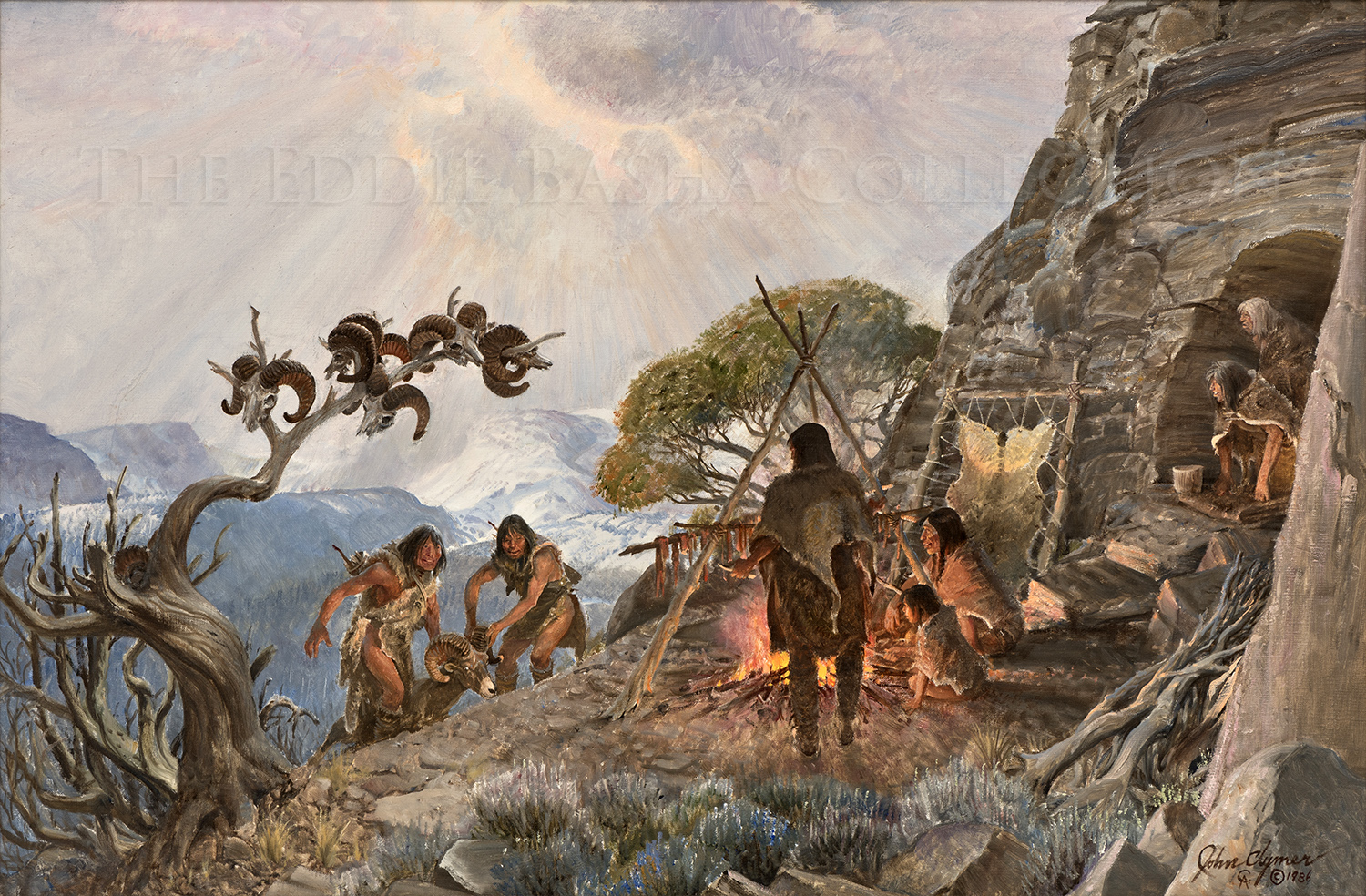

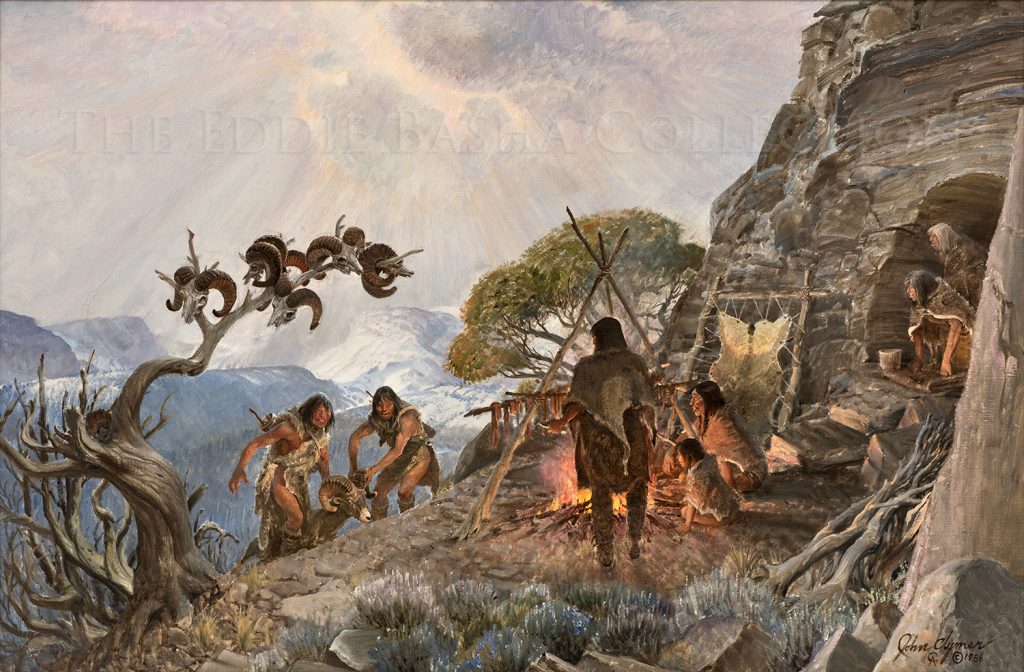

Sheepeaters

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1986) | Image Size: 24”h x 36”w; Framed Size: 35”h x 47”wpainting

The Shoshone, once spread throughout the great basin and plateau areas of Idaho, Utah, Montana and Wyoming, often designated or referred to the different branches of their people by the predominant food which the group ate. Thus they had at one time fish eaters, salmon eaters, seed eaters, elk eaters and sheepeaters. The Sheepeater band was so called because its main diet was the Rocky Mountain Big Horn Sheep. This Shoshone group lived in the high mountains. They were also known to the older Shoshone as the mountain people. Whereas the Plateau Shoshone experienced a great transformation in their culture after they acquired horses in the 1700’s, this mountain branch never acquired horses. They continued to maintain their isolated way of living which was well adapted to the harsh climate of their rugged mountain home. Lacking means of transportation when moving and depending on frequent migration or moves as they followed and hunted large game, they lived and traveled on foot in small groups consisting of one or two families carrying their few possessions in woven baskets of sagebrush and bark.

Their summer months were spent following the large game animal in their migrations to high timberline pastures. Their residences were maintained in lowly places and clefts in the rocks. When the game moved to lower elevations for wintering, the Sheepeaters followed. For travel on snow, they used snowshoes which they made from mountain sheep horn.

The hunters sat in their rock cairn blinds on high, bare ridges watching for game. From the amount of chippings on the ground on these ridges, it is surmised that the Sheepeaters would come to these sites with their hunting equipment and sit during the day chipping out projectile points and tools. In the evening as the game came out to feed and was sited, they would rise quietly for the stalk. If they were lucky a kill would be made. If there was no luck in one draw, they could move to another. To ensure success in hunting they sometimes placed a ram’s skull in the branches of a tree. In the early days the atlatl and the spear were used as weapons. Later the bow and arrow came into use. Their spear and arrow points were chipped from agatized wood, flint, volcanic rock and obsidian. The sheepeaters were very adept at making a strong mountain sheep horn bow which was a very popular trade item with other Indian groups. Also they were well known for the fine tanned hides they finished and the warm winter clothing they fashioned.

In winter instead of a skin lodge, the usual sheepeater shelter was the wikiup made by bracing aspen poles together at the top to form a conical structure with pine boughs interlaced on the outside. They also made use of natural caves in the rocks.

In addition to the small hunt for an animal or two, they were known to have constructed sheep traps into which a herd of game were driven down into a pen or open pit from which they could not escape. Remnants of these old traps and the rock cairns on the high bare ridge top where the lonely hunters watched for game may still be found today in the Absaroka and Wind River Mountains. Also to be found is an occasional decaying wikiup in some secluded spots.

In the painting, a small family group of sheepeaters living in a mountain cave welcome the arrival of two hunters who come dragging in their mountain sheep kill. The tree in front of the cave is adorned with mountain sheep skulls, testimony to their skill in hunting.

Sacajawea at The Big Water

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1974) | Image Size: 24”h x 48”w; Framed Size: 35”h x 58”wpainting

One of the greatest adventures in American history was the Lewis and Clark Expedition which set out to explore the vast, unknown territory of the Louisiana Purchase in 1804. It resulted in a fantastic journey from the banks of the Mississippi to the shores of the Pacific Ocean and back. The round trip took more than two years and had tremendous influence in the subsequent settlement of the American West.

The cast of characters in this dramatic initial chapter of western history were the two leading men, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark; but the most intriguing character was an Indian woman, Sacajawea. While the expedition was in winter camp at the Mandan Villages in North Dakota in 1805, they secured the services of an interpreter named Toussaint Charbonneau, a French-Canadian trapper whose young wife, Sacajawea, and her new baby accompanied her husband and the Corps of Discovery on the journey. Sacajawea’s contributions were incalculable to the success of the expedition as she provided skills related to direction, translation and communication, the acquisition of fresh horses, foraging for wild edibles and medicinal herbs, tending to the infirmed, cooking, and all the while caring for and carrying an infant who became a toddler along the way. She was not only an invaluable asset to the party, but her and her child’s presence was a sign of its peaceful intentions by others they met along the way until the corps reached its goal, the mouth of the Columbia and the Pacific Ocean.

A great moment came for Sacajawea when after having accompanied Clark’s party to the beach where a whale had washed ashore, she was at the Pacific Ocean for the first time; she called it “Big Water”.

This masterwork was the 1974 Gold Medal Winner in Oil at the Prix de West Exhibition & Sale held at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

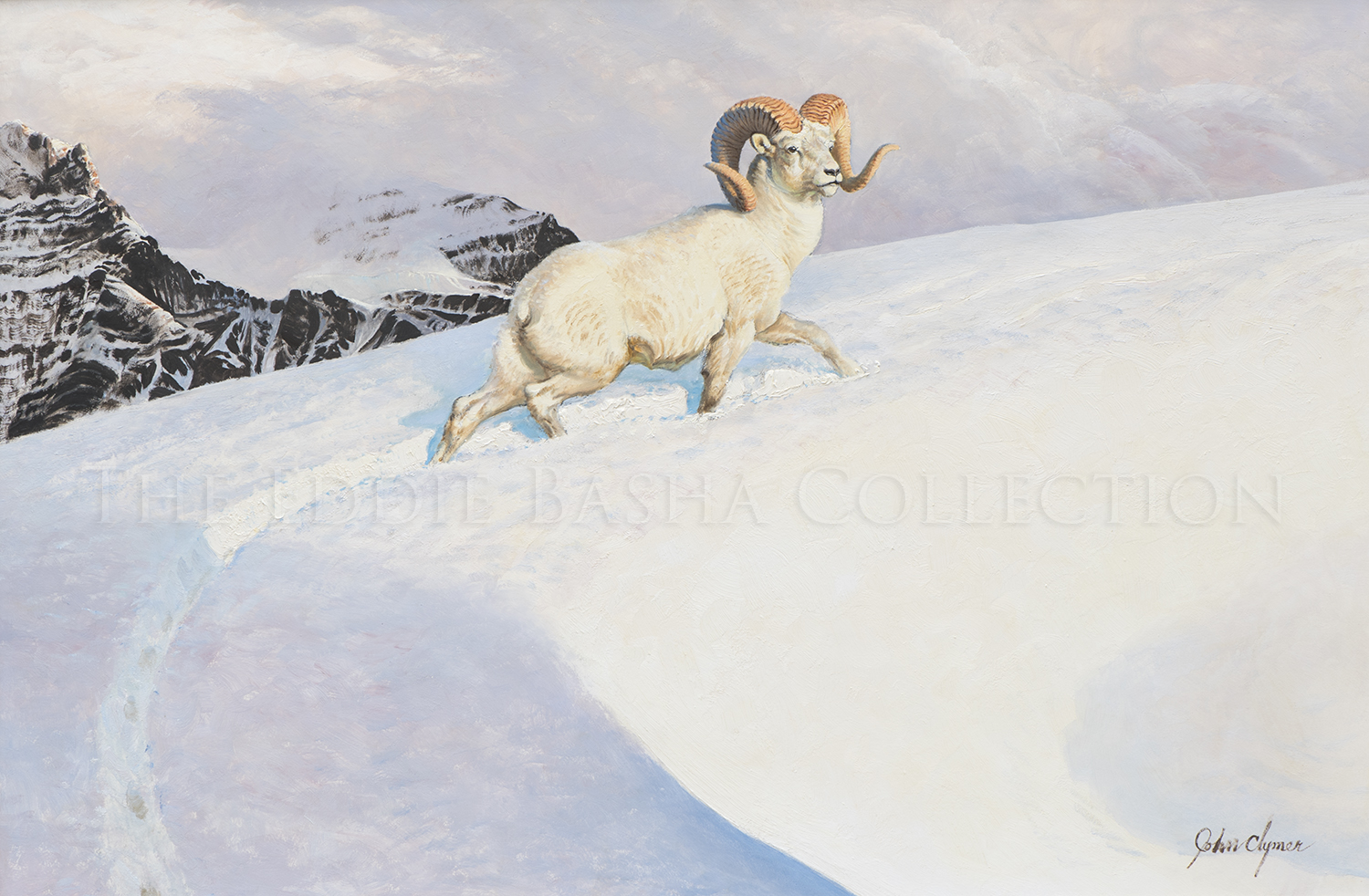

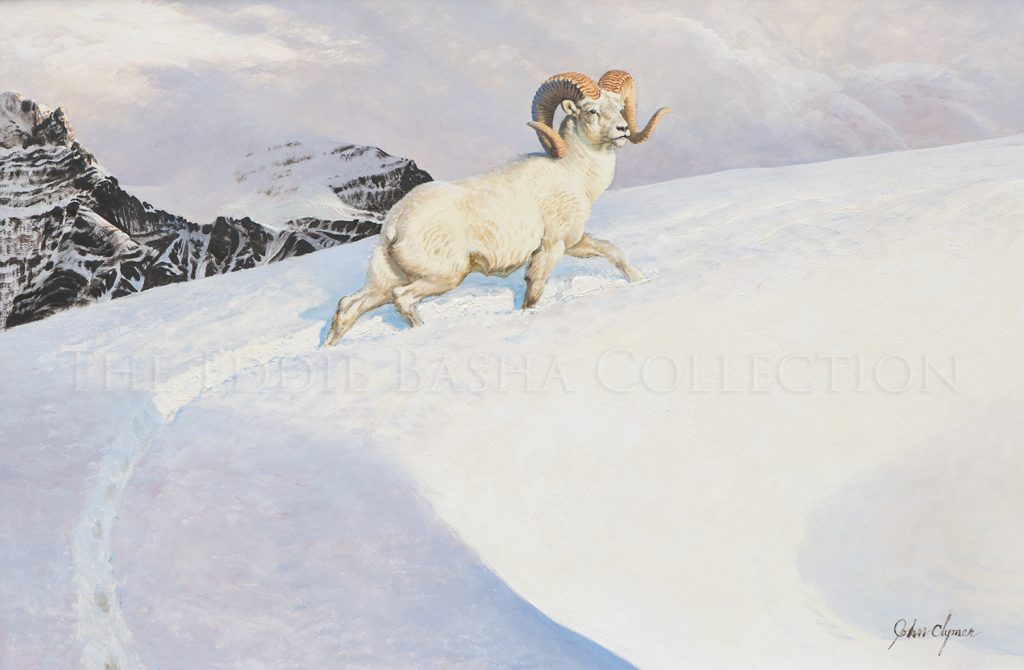

Dall Sheep

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil | Image Size: 24”h x 36”w; Framed Size: 36”h x 47 ½”hpainting

Dall sheep, the real world cliff hangers, can be found in some of the most rugged alpine areas of Alaskan and Canadian territories. On average they weigh in at 130 pounds and have white fur. The ewes typically only birth one lamb in the spring which can walk within 24 hours. Though twins are rare, nursery groups are often formed amongst the species to watch over the offspring while others forage or rest. Dall sheep meat though excellent, is difficult to harvest due to the inaccessibility of areas inhabited.

In similar fashion to his historical paintings, John Ford Clymer has shown here his ability to accurately render the anatomy of an animal and his use of light adds a dramatic touch. The sheep is caught in a bright shaft of sunlight that freezes the action and offers a contrast with the darker snow and cloudy sky behind.

A photo image of “Dall Sheep” is depicted on page 147 in the book entitled “Animal and Sporting Artists in America”, authored by F. Turner Reuter, Jr., and published by The National Sporting Library, 2008.

Devil’s Gate: Fitzpatrick 1824

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1986) | Image Size: 40”h x 30”w; Framed Size: 50”h x 40 ¼”wpainting

Survival depended on resourcefulness for the men who came early to the West. The Rocky Mountains were a world away from the frontiers of settled America, and the country was vast and unknown. Yet, men did come to the distant, remote places. They were lured by the promise of profit to be gained in trapping for beaver pelts and other furs.

In the spring of 1824, a band of these rugged men found their supplies depleted after a long winter of trapping in the Green River region of Montana and Idaho. Thomas Fitzpatrick and two companions were sent on the long journey eastward to carry out the furs and to bring back fresh supplies.

Arriving at the Sweetwater River, the three men found the water swollen by snowmelt. They built a bullboat from buffalo hide stretched over a willow frame in Indian fashion. It was their plan to float the furs down the Sweetwater to the Platte, then on to the Missouri which would carry them all the way down to St. Louis.

A few miles upstream from Independence Rock which would become a prominent landmark for a generation of travelers on the Oregon Trail, Fitzpatrick and his men passed through a notch in the rock called Devil’s Gate. Ingenuity was not always enough to overcome the challenge of the wilderness. Shortly after passing through Devil’s Gate, the water became too shallow to float the fur-laden boat, and the men were forced to hide their cache. They continued on foot to the Missouri for the trip down to St. Louis for the supplies which would sustain the party through another season of trapping. In those long ago days, civilized men had no clear advantage in dealing with life in a wild and primitive land.

The Peace Pipe, Overland Astorians 1811

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1979) | Image Size: 24”h x 48”w; Framed Size: 34 5/8”h X 58 5/8”wpainting

The history of the western fur trade contains more high adventure and drama than could be created by a novelist’s imagination. There is no better example of this than the story associated with Fort Astoria.

When John Jacob Astor decided to establish a trading post at the mouth of the Columbia River on the Oregon Coast, two parties were sent out. One party went by ship from New York in 1810. The other, called the Overland Astorians, started up the Missouri River in the spring of 1811 under the leadership of Wilson Price Hunt.

A primary concern of the Overland Astorians as they travelled upriver was the ever-present danger of hostile Indians. On May 31, 1811, the Astorians met a large Sioux war party that was determined to oppose their progress upriver so as to prevent trade with their enemies. The Astorians made resolute preparations for defense and were greatly relieved when the Indians, who vastly outnumbered them, made the sign for parley.

We are witness to the scene as Hunt and some of his men join the principal Sioux warriors and share in the smoking of the ceremonial pipe. It is an impressive moment as the pipe bearer lights the calumet and presents it to the sun and the four points of the compass before sharing it with the assembled circle. On this occasion the red man and the white man have indicated a mutual respect for one another. The Astorian party was allowed to proceed on its way unmolested.

Traders on the South Pass

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil | Image Size: 24”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 35”h x 50”wpainting

The year is 1834 and the vast country reaching westward beyond the Mississippi River remains wild and unknown to the young Nation that claims it. Bold men in search of fortune and adventure accept the wilderness challenge and sow seeds of heroic legend beneath wide open skies.

At the western terminus of the long trek was the promise of a treasure in exotic furs eagerly desired by American and European fashion houses. Top hats, made from the pelts of the western beaver, were a singular mark of distinction for distinguished gentlemen in New York, Paris and London.

Indian bands set aside traditional feuds temporarily and gathered during the early summer in broad grassy meadows beneath towering mountains. They came with furs to trade with the white men for strange and wonderful things like brilliantly colored cloth and glass beads, metal tools, rifles and powder, and the bitter tasting drink that induced a state that seemed something near the experience of a vision quest.

In this year of 1834, the enterprising white men rush west for the annual meeting with the Indians. The event has come to be called Rendezvous … a magical word which conjures up images of feathers and paint, of prancing spotted ponies, of wood smoke drifting on the clear mountain air and the pounding thunder of steady drumbeats.

This is William Sublette’s trade caravan crossing South Pass in the Rockies on his way to the 1834 Rendezvous at Ham’s Fork. Sublette drives his men and animals hard to reach the site east of the big mountains before his competition, particularly Nathaniel Wyeth who is also racing toward the trading ground. The fur trade has become big business by 1834, scarcely three decades since Lewis and Clark blasted their way across the Rockies. The first white traders to reach the Rendezvous will reap ample reward for the long, difficult journey out and back through the trackless regions beyond St. Louis to the distant mountains where Indians, still proud and free, bring forth a fortune in furs.

Source: Doris & John Clymer, the Artist

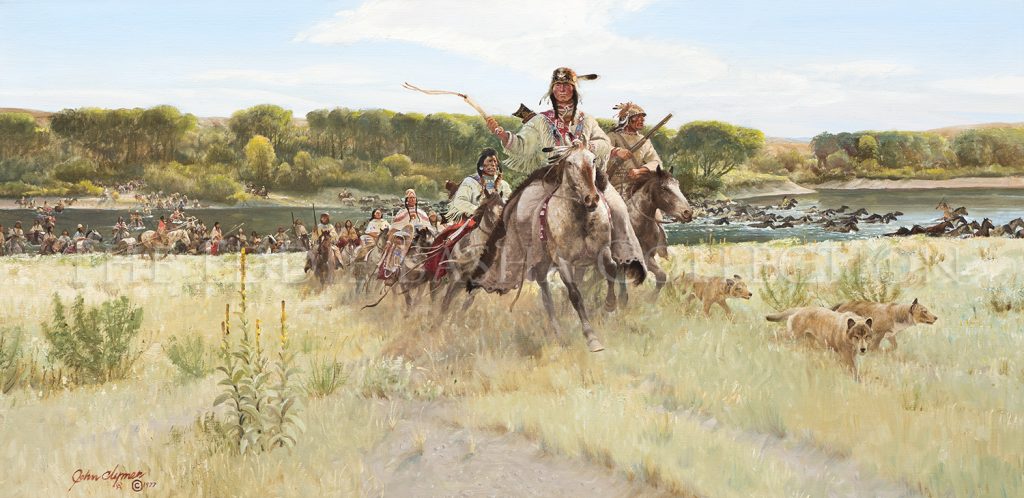

Nez Perce Crossing the Yellowstone 1877

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1977) | Image Size: 24”h x 48”w; Framed Size: 35”h x 58 ½”wpainting

Source: Doris & John Clymer

An epic western drama was played out in the summer and early autumn of 1877. The government decreed that the southern Nez Perce should move from their traditional homeland in northeastern Oregon to a reservation in the Idaho panhandle. Angry young men went on a rampage killing several settlers and incurring the wrath of the U.S. Army which was eager to avenge Custer who had fallen only a year earlier at Little Bighorn.

Chief Joseph, leader of the five bands who had been ordered onto the reservation, now led his people, 700 men, women and children, across the mountains in a desperate flight to escape the pursuing soldiers. For 108 days, Joseph’s people travelled east across the mountains, out onto the Plains, and then north toward the Canadian border. Under constant pressure from the superior forces of the Army troops, the Nez Perce repelled a series of attacks, though suffering heavy losses.

Finally, on October 5, only forty miles from the safety of Canada, with a snowstorm blowing in, Joseph surrendered on the bleak Montana Plains. They had come 1700 miles and only 431 Nez Perce were left of the 700 who had begun the journey. The survivors were cold, starving and dispirited.

In his surrender to Colonel Nelson A. Miles, Chief Joseph said: “It is cold and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. I want time to look for my children. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs. I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

Clymer presents yet another complex scene with numerous figures in a panoramic setting to offer a glimpse into the tragic story of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce. Clymer has chosen to show these courageous people not in defeat, but during the arduous journey. Chief Joseph is shown at the point of a compositional triangle that fans out with the Nez Perce people and their animals behind him.

This magnificent painting was exhibited at the Gilcrease Museum (Feb-April 1987), the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum (March-June 1991), The Wildlife of the American West Museum (June-Sept 1991) and The Autry Museum (Sept.-Nov. 1991).

The Métis Brigade

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil | Image Size: 20”h x 40”w; Frame Size: 29 ¼”hx 49 ¼”wpainting

Throughout the New World, the cultures and blood of Europeans mixed with those of Native Americans. In south central Canada, along the Red River which runs north to Lake Winnipeg in Manitoba, lived the Métis. These were the descendants of the early French trappers and their Indian wives. Métis is the French term for mixed blood, or half-breed.

Each year the Métis travelled south to hunt buffalo out on the Great Plains. Women and children rode in carts handmade of wood and fastened together with wooden pins and rawhide. The rims of the wheels were also bound in wet rawhide which, when dried, formed a surface much more durable than exposed wood. They were called Red River Carts and were similar to the Chihuahua carts used by Mexicans down along the frontiers of New Spain.

The annual trek was a family affair eagerly anticipated by entire villages. Each cart was identified by a pennant, or some other emblem of an individual family’s pride. It was a colorful scene and a happy time for all the Métis, both young and old.

There was a French presence in the Old West long before the Americans arrived. French names were given to Indian tribes like Nez Perce (Pierced Noses) and Gros Ventres (Big Bellies). The Indian conveyance made of poles and pulled by dogs or horses became known by the French word “travois”. Trappers called their stockpile of furs and supplies “cache”. And the spectacular mountains of northwestern Wyoming are still known by the name given them by the French trappers who first saw them, “Grand Tetons”.

Beaver Stream

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil | Image Size: 24”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 34 ¼”h x 50 ¼”wpainting

Early in the nineteenth century a few remarkable men carved out a timeless legend in the uncharted wilderness of the American West. They were tough and resourceful; wild, free men in search of adventure. Alone or in small parties, they set out from St. Louis, traveling on flatboats to the headwaters of the Mississippi River and then out into the unknown country along the timbered slopes of rugged mountain chains.

They set traps along remote streams of clear, cold water to catch beaver. The pelts would ultimately end up as top hats on the heads of gentlemen that strolled the streets of Paris and London. The men who wore those beaver top hats could scarcely imagine the contrast and distance that separated their world from that of the men who challenged fate in a land that was both savage and beautiful.

Those who came in search of the beaver were motivated by something deeper than commercial ambition. Trapping was what they did; but it was not what they were. It was the grand adventure that called them away from civilization to the lonely life where they could truly be free. Life back east of the Mississippi had already begun to smother the pioneer spirit that had characterized America in its earlier history. These first men who went west were still stirred by the wilderness siren song.

History records little of this special breed of men. Few of their names are known, and in less than a generation, the West would be opened to waves of overland migration. Civilization would once again close in on those who had come West to escape it.

Source: Artist

Rocky Mountain Bighorns

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil | Image Size: 20”h x 30”w; Framed Size: 30”h x 40”wpainting

High above the timberline up where snow blows and the wind howls across sheer rocky slopes, a pale ghostly presence roams freely in the harsh environment. The mountain sheep is a wild breed at home along the rugged backbone of the Rocky Mountains. This is a creature that inspired reverence among the Indian hunters who first beheld them from the forests down on the lower mountain slopes. The fur trappers and explorers who ventured beyond the western boundary of the vast plains were awed by these strange, wonderful creatures.

The majestic bighorn bounded on the bare rock surfaces, up and down steep precipices where snow drifted into the blue shadows of high crags and peaks. The bighorn is a survivor of the ages in bitter surroundings of incredible beauty.

This is a timeless image of the primal western wilderness, of a land unspoiled by the hand of man – the mountain sheep portrayed with its natural grace and dignity in the alpine solitude that is its home.

Lord of the Plains

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1987) | Image Size: 15”h x 30”w; Framed Size: 23”h x 38”wpainting

It was a grand and golden time on the buffalo range. The northern Great Plains was home to the Indian, and in this place, at this time, he was proud and secure. Horses, brought to the new world by the Spanish, had transformed a primitive nomadic people into a highly mobile and efficient society of hunters and warriors.

The white man had not yet ventured into the Plains area in any significant numbers as the nineteenth century began. The timeless tradition of Native American life was in full flower. Nature provided for its children with abundance. Great herds of buffalo were an endless source of meat, hide and horn; the sustenance of life for a people who lived in harmony with the land and were grateful to the Great Mystery Power who had put them there.

This scene is in the White River country of southwestern South Dakota and northwestern Nebraska. Here was the domain of the mighty Sioux. Their attachment to this land had been forged through the generations. In the years to come, white men would discover just how strong this attachment was. But for now, the Sioux were masters of all they surveyed; a people existing in harmony with nature, as much a part of the natural order as their spirit brothers, the wolf and the hawk.

The open prairie stretches out beneath western skies. A band of Sioux is moving across the Plains in preparation for the fall buffalo hunt. The men tell tales of valiant horses and of brave men riding into thundering herds for meat and honor. The women see to the transportation of the camp and anticipate warm robes and plentiful food for the coming winter. These are the images of a glorious time, of a world that would too soon be gone.

After the Hunt

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1972) | Image Size: 24”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 34”h x 50”wpainting

It is early morning and the sun is coming up out on the Great Plains. This is the day following a successful hunt. Buffalo carcasses litter the landscape as women and children begin the work of skinning off the hides and cutting up the meat. It is quiet now in this same place where only yesterday the thunder of hooves echoed across the prairie, dust clouds boiled high into the sky and brave men rode their horses in and among the stampede to place swift, sure arrows.

The Plains Indian was linked irrevocably to the buffalo. It was the mighty herds of animals beyond counting that first drew the Indian away from the woodlands to the east, out onto the rolling prairies of tall grass. Other Indians might plant and harvest crops and live in permanent settlements or sturdy dwellings. But, for those who would follow the buffalo, life was perpetual mobility. They were a society of nomads moving their homes and their culture from place to place in pursuit of the great shaggy beasts.

The buffalo was the source of practically everything the Plains Indian needed to survive. Buffalo meat was the staple of their diet. Hides were made into clothes as well as the covering for the lodge poles of their homes. Rawhide was used for shields, lariats, parfleche bags and to bind points on arrows. Horn and bone were shaped into a variety of tools and implements. Dried paunches were used as cooking pots, and even hair was used to pad cradleboards and stuff pillows.

The buffalo was so pervasive in the life of the Plains Indian that it was accorded a special reverence by the very same people who shot their arrows into its heart. Buffalo skulls were a focus of many ceremonial rituals. Great chiefs and medicine men took names associated with the buffalo to increase their personal prowess. As long as the great herds flourished, so too would the Indian of the Plains.

In 1991, this painting along with several other Clymer masterworks went on tour. “The West of John Clymer” was shown at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum (Oklahoma City, OK), the National Museum of Wildlife Art (Jackson Hole, WY) and at The Autry Museum of the American West (Los Angeles, CA).

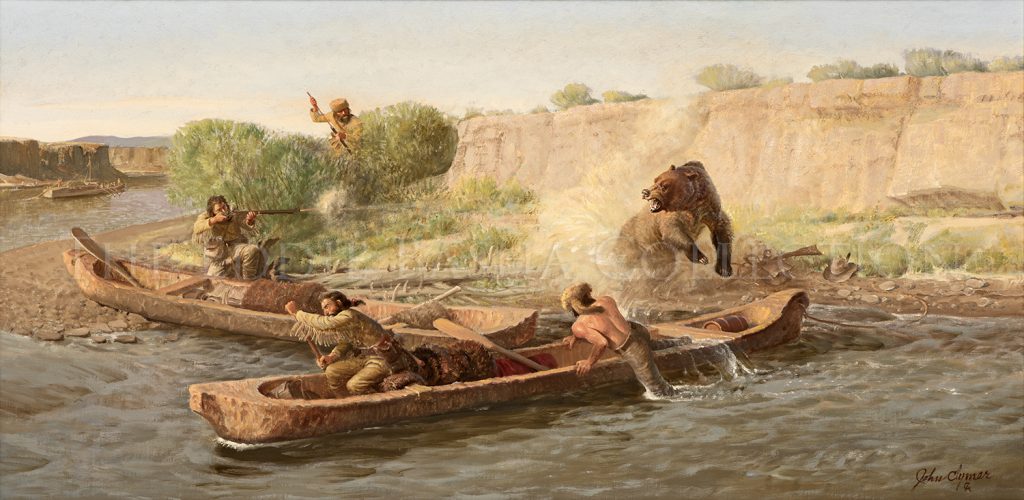

Hasty Retreat

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1973) | Image Size: 20”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 30”h x 50”wpainting

There were many hazards encountered in early travel on the long and wandering course of the muddy Missouri River. But men would come, lured by stories of a bonanza of furs and for the chance of adventure. Over three thousand miles the great river twisted and turned past ever-changing and dramatic panoramas. It was a world very different from the settled country back down river where towns and farms spread across the landscape. Life back East had become routine. Men there accepted mundane jobs and were content to live in close proximity to their neighbors.

The Missouri was a shining path leading westward. Twenty-three miles north of St. Louis it emptied into the Mississippi. Its course upstream moved west across Missouri, then turned north and northwest dividing Kansas from Missouri and Nebraska from Iowa on through the middle of the two Dakotas, then west again parallel with the Canadian border to far Montana, dipping back southwest finally to the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains.

The prospect of danger waited around every bend for men who would challenge the big river. In this scene, a group of trappers have come ashore to hunt for their supper. The hunters quickly become the hunted when, with sudden and violent ferocity, a giant grizzly bear springs to attack. Single shot muzzle loading rifles are inferior to the raw savagery of tooth and claw. The men scramble desperately to gain the safety of deep water. One man is cut off from the boats and frantically rams a new charge into his rifle. When wounded, the grizzly will become even fiercer in its assault. On days like this, men paid a high price for free life in the far West.

Down the South Platte – Jean Baptiste Charbonneau 1842

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1981) | Image Size: 20”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 30“h x 50”wpainting

In the spring of 1842, company employees of Fort St. Vrain, under the leadership of Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, had a tiring journey as they started carrying the robes from the fort by boat down the South Platte River to St. Louis. Although other trips in previous years had successfully used this route, the water in the river was much too low this year and the journey was toilsome and tedious; the men literally having to drag the boats over the sandbars.

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau was the son of Sacajawea and Toussaint Charbonneau who, as a baby, had accompanied his parents on the Lewis and Clark expedition to the Pacific Ocean and back. He had been educated in St. Louis under the guardianship of Captain William Clark. When he was 18 or 19, he was taken to Europe by Prince Paul of Wurttemberg where he remained for five or six years during which time he travelled about with the Prince accompanying him to Northern Europe and Africa. He became fluent in several European languages.

On his return to America, he worked for a number of years for the Bent, St. Vrain & Company and also as a guide on several major expeditions, the most famous perhaps being his employment as a guide to Colonel Philip St. George Cooke when, at the time of the Mexican War, he lead the Mormon battalion from Santa Fe to San Diego where he remained for a number of years. He died in 1866 on a trip returning to the gold fields in Montana, the land of his youth, and was buried in Jordan Valley near present day Danner, Oregon.

Charbonneau dominates the center of the painting and is placed in the foreground striding toward the viewer. The other trappers and their boats are shown to the right of Charbonneau and to his rear. Clymer has composed the painting to put the viewer’s full focus on Charbonneau as the leader and primary figure in the party. The horizontal shape of the canvas allows Clymer to present a panoramic view of the landscape while still allowing a focus on the main figure. The fur trade era of the American West was one of Clymer’s preferred subjects to paint. Might you know one of his other favorite subjects?

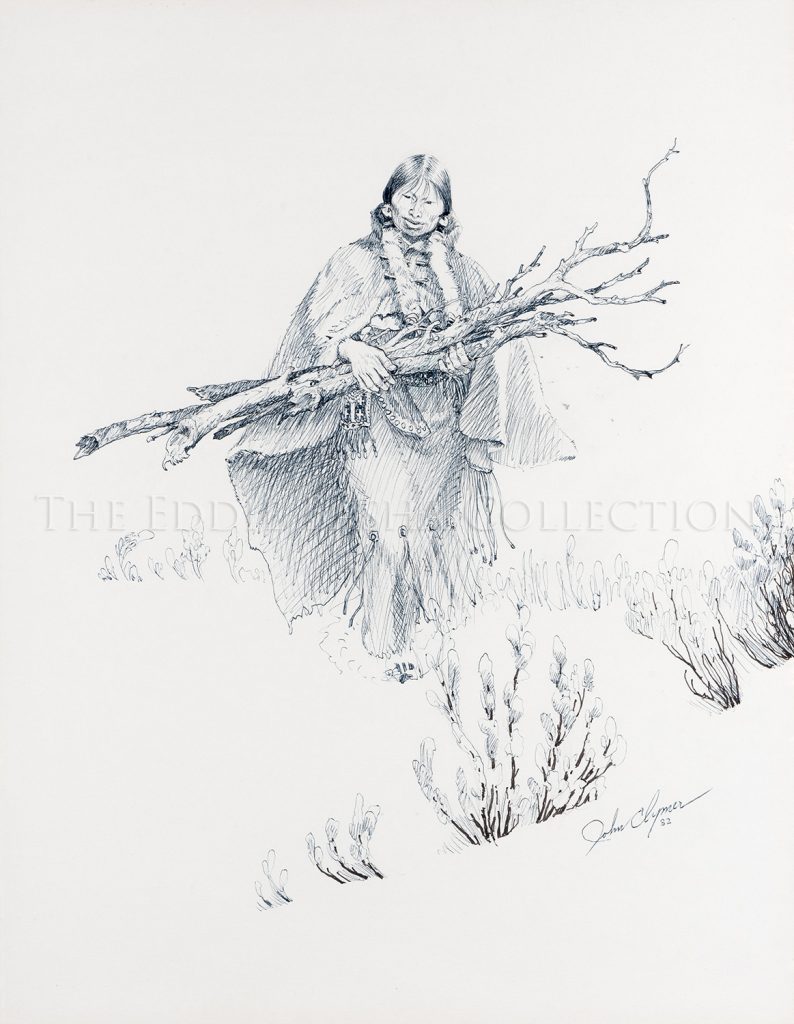

Sacajawea

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Pen & Ink (1982) | Image Size: 18”h x 14”w; Framed Size: 29”h x 24”wdrawing

Sacajawea, the lone Indian woman who accompanied and aided Lewis and Clark and 43 other men, including her husband, on their epic journey to the Pacific Ocean was one of the historical figures John Ford Clymer illuminated often with great reverence. Her contributions were incalculable to the success of the expedition providing skills related to direction, translation and communication, the acquisition of fresh horses, foraging for wild edibles and medicinal herbs, tending to the infirmed, cooking, and all the while caring for and carrying an infant who became a toddler along the way.

Here, Clymer has sketched Sacajawea gathering wood for a fire. Clymer has focused solely on his subject and has not finished the background of the drawing, which serves to both isolate her and to emphasize her importance to the Corps of Discovery, to history and to the artist. She is shown engaged in a simple task, one that she most likely repeated each day of her journey with the explorers. The overall effect is to convey to the viewer a true sense of the day to day reality of her life, rather than place her in a more dramatic and adventurous setting. While the latter scenario would make for a good story, the drawing as it stands is reflective of the true history during the period as well as her singular female status.

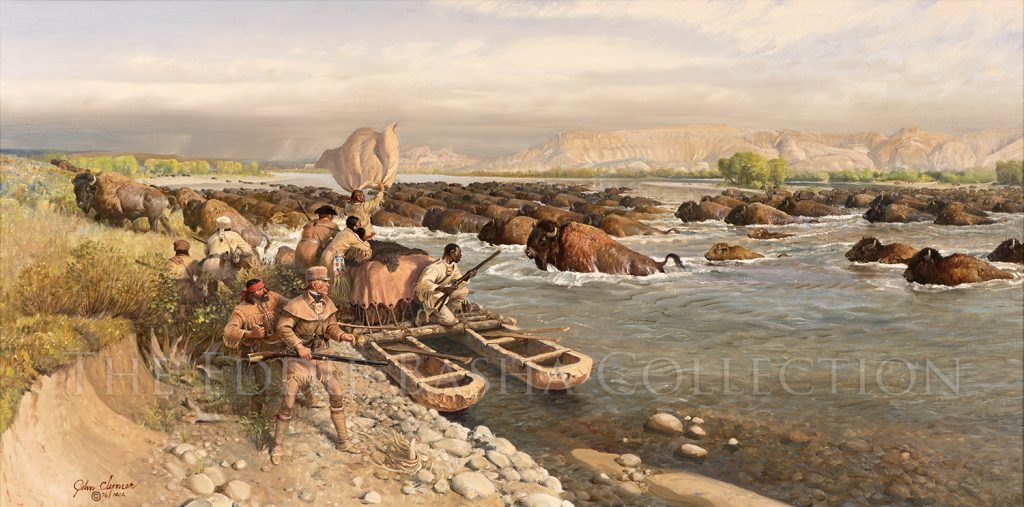

Captain Clark Buffalo Gangue

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1977) | Image Size: 24”h x 48”w ; Framed Size: 35”h x 59”wpainting

On March 23, 1806, the men of the Lewis and Clark party began their return journey to St. Louis and civilization. The expedition split into two groups. Lewis, along with nine men set out to explore and map the Marias River. The remaining men under Clark continued to the Three Forks of the Missouri in present day Montana.

At the Three Forks, they recovered the boats which had been left on the journey westward. Clark then dispatched nine men to meet the Lewis contingent at the junction of the Marias and the Missouri Rivers. Clark and the remaining men set out overland to explore the Yellowstone River. They build two crude canoes, lashed them together and began their trip down the river. This painting, Buffalo Gangue shows Clark and his small band on the afternoon of August 1, 1806, encountering an enormous herd of buffalo crossing the Yellowstone. Consequently, the men were forced to land their canoes until the herd passed. It was a magnificent sight. The buffalo herd seemed to have no end. Clark described them as gangue of buffalo. This incident was but one of many dramatic episodes which were a part of the grand adventure of the Corps of Discovery. Each member of the group retained vivid impressions and memories of scenes such as this.

This entire expedition reunited near the mouth of the Yellowstone in mid-August and began the boat trip back down the Missouri. They were back in St. Louis before the end of September. Theirs was a singular and distinguished accomplishment in the history of Western America.

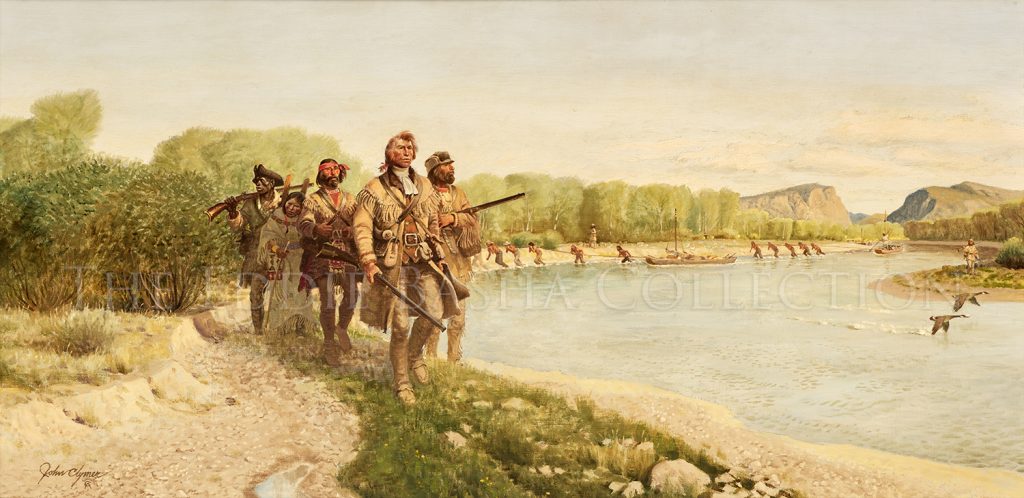

Up The Jefferson

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil | Image Size: 20”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 30”h x 50”wpainting

The epic journey of Lewis and Clark was the genesis of America’s thrust westward across the continent. In 1803, the United States obtained from France, by terms of the Louisiana Purchase, all the land between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains, from the Gulf of Mexico to the Canadian border. From 1804 to 1806 an official expedition was dispatched to explore this vast, new territory and report back to Washington. The expedition, under joint command of Captain Meriwether Lewis and Second Lieutenant William Clark, was comprised of individuals representing the ethnic diversity of the new Nation. White of European ancestry, Canadian voyageurs of mixed French and Indian heritage, a black slave called York who belonged to Captain Clark, and a valiant Indian woman called Sacajawea.

The Corps of Discovery experienced both hardship and triumph over the two year adventure that took them up the Missouri River, out onto the Great Plains, over the barrier of the Rocky Mountains, to the shores of the Pacific Ocean, and then the long, hard journey back. The formal report spoke in glowing terms of a country of fertile prairies, flowing water, towering forests, abundant wildlife, and an endless succession of awe-inspiring natural wonders. As to their encounters with the native population, Lewis and Clark reported that they had, for the most part, found the Indian to be friendly and hospitable. It was a story that quickly captured the Nation’s imagination.

In this John Clymer oil entitled “Up The Jefferson” it is the summer of 1805, the expedition is on its return voyage proceeding up the north fork of the Missouri River, which they named the Jefferson, in honor of the American President. A small group is being sent off overland to secure horses from the Indians. The rest of the party will continue on the river in their rough-hewn canoes. It was still a long way home.

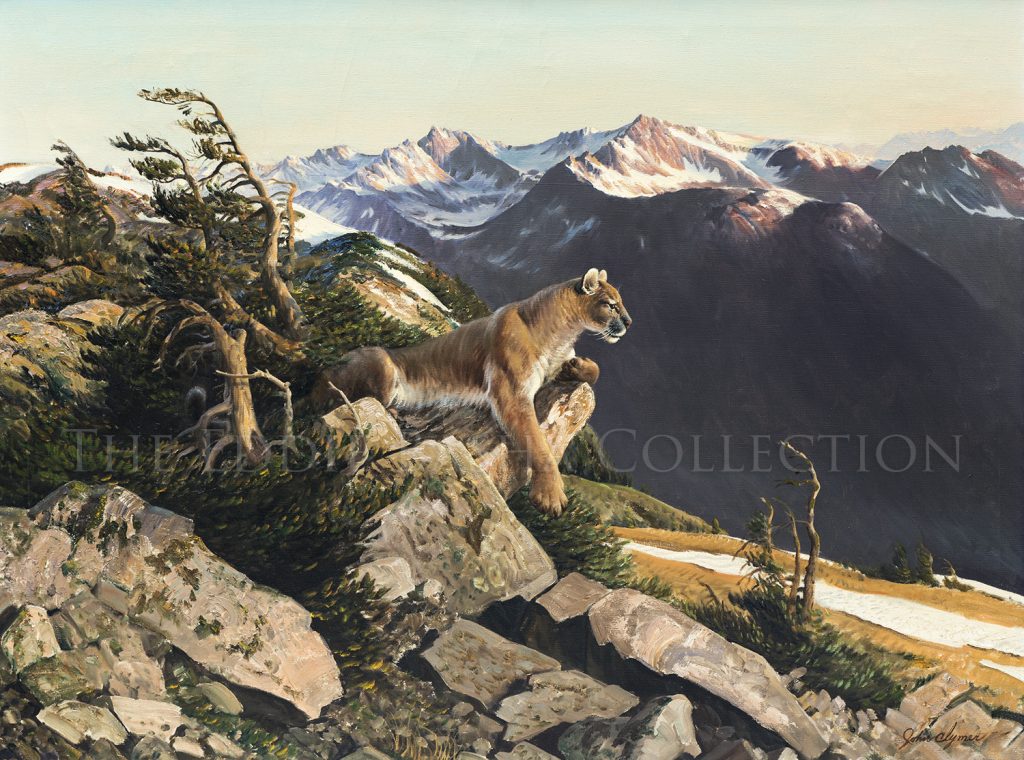

Cougar

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil | Image Size: 30”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 40”h x 50”w

In this large wildlife and landscape painting, Clymer focuses his attention on two of his favorite subjects, the splendor of the Rocky Mountains and the beauty of one of its most revered creatures, the cougar.

Clymer had a deep respect and admiration for both the land and its inhabitant which are presented here with equal weight. The cougar, which is granted the painting’s center stage, is shown as an integral part of the natural environment. Lolling atop a sunny rock, he surveys the entire valley below him. By following his gaze, we are accorded the same viewpoint that he has and through him, we are introduced to a landscape that is grand in scope; it is a scene that calls for a second and third look. The cougar is both the subject of the painting and our guide to linger awhile and appreciate the wonder of nature.

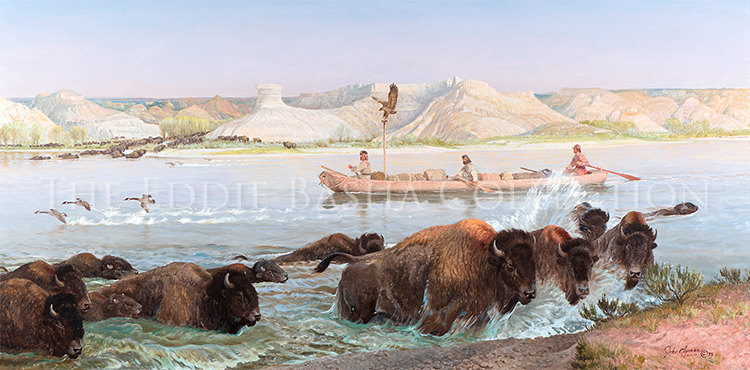

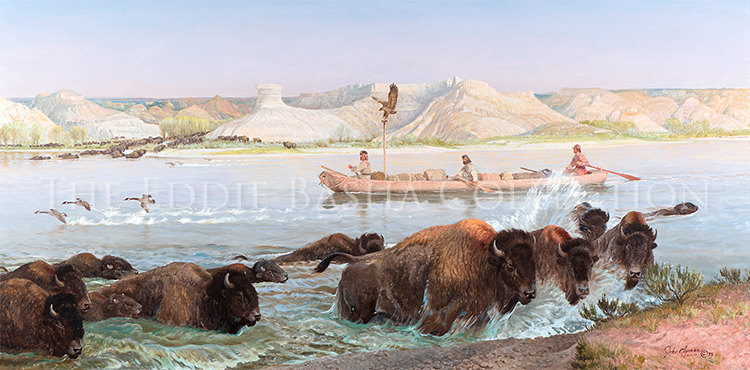

George Catlin - Return Journey 1832

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1975) | Image Size: 30”h x 60”w; Framed Size: 40”h x 69”wpainting

In the spring of 1832 when the steamboat “Yellowstone” made its first trip up the Missouri River carrying supplies from St. Louis to Ft. Union, a 2000 mile journey, the artist, George Catlin, was aboard. The purpose of Catlin’s voyage was to paint the Indian Tribes of this remote area. After a month stay at Ft. Union during which time he painted numerous portraits of Indians from various tribes of the region as well as portraying scenes and customs of Native life, there Catlin with two trappers he had met embarked in a rude canoe for the return journey to St. Louis.

The boat was well loaded with food, ammunition, all Catlin’s sketches, art materials and Indian artifacts which he had acquired on his journey. His two companions rode in the middle and in the bow of the boat while Catlin sat in the stern, manning the steering oar. Another companion was the “war eagle” which Kenneth McKenzie, the bourgeois at Ft. Union, had given him. Catlin erected a perch for it on the boat. It was so tame it was satisfied to stay with them either sitting on its perch or flying overhead.

Travelling on his own in this manner, Catlin was free to stop at the Indian villages along the river and to wander, paint and make notes wherever he chose. As they travelled along the river, they saw great herds of buffalo along the banks as well as other game, also a variety of ducks, geese and other birds. Fresh game was always plentiful.

In the picture, George Catlin and his companions, Bogard and Baptiste, are drifting down the Missouri River accompanied by the mascot, the eagle.

This piece was also included in “The West of John Clymer” exhibition in 1991 at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, the National Museum of Wildlife Art, and The Autry Museum of the American West, and a photographed image of the piece appears in several books as well. The original oil painting remains a permanent part of The Eddie Basha Collection.

Narrative Source: The Artist

Beaver Catch

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1974) | Image Size: 24”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 34”h x 50”wpainting

East of the Mississippi, America was becoming settled and civilized as the eighteenth century drew to a close. People were getting used to living close to each other as towns grew into cities and farming communities sprung up to feed the growing population. But as in an earlier day, there were men who craved the challenge of more distant places and the freedom and excitement of a life lived on the raw edge. Out West where the sun went down in the shadow of the great Rocky Mountains, these men sought adventure and wealth.

Fashionable gentlemen of the day on the East Coast and in Western Europe were wearing stylish top hats made from beaver pelts. Demand for the pelts far exceeded the supply and the prospect of profit lured men to the remote wilderness where the beaver could be found. These were the free trappers and mountain men; those who would form the vanguard of America’s move westward.

Danger was ever present, and the lonely isolation broke the spirit of more than a few. In this scene, two men are working their trap line. This was done either in the early morning or near sundown when there was less chance of being discovered by hostiles. The trappers were, after all, trespassers in someone else’s country. A flintlock rifle is close at hand.

These were the men who brought back stories of the wonderful land that lay beyond the frontier. Their exploits make up one of the most colorful and dramatic chapters in the history of the American West.

Clymer’s quiet painting of two trappers reviewing their catch along a placid stream under a setting sun shows his skill in creating a mood and sense of place. He presents a vision of the West that is far different from his action scenes. The two trappers are bathed in the pinks and golds of the setting sun fostering serenity. Clymer also shows admiration for the bounty of the West at a time when only a few traders and trappers roamed its mountains.

The Providers

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1983) | Image Size: 30”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 41”h x 51 ½”wpainting

Winter came early and stayed long on the northern Great Plains along the edge of the mountains. Survival during the season of cold winds and deep snow depended on the people’s ability to select a good location for their camp and store up sufficient provisions.

Summers were devoted to the buffalo hunt. Entire villages followed the great herds across the prairies. Men did the killing and women prepared and packed the meat and hides. After the months of hunting, a winter camp was established, usually among low hills which would provide protection from howling blizzards. Proximity to a river or permanent stream was also a major consideration in the selection of a camp site.

Through the fall, the camp was hard at work in preparation for the approaching winter. Women dried buffalo meat in the sun and tanned hides for clothing and warm robes. Children gathered edible roots and berries for storage. The men hunted close by for elk, deer, antelope, and other small game. Wood was gathered and stacked near the lodges. The horses were closely herded until they got used to grazing comfortably near the camp.

The bitter wind swept down off the mountain slopes finally, bringing the ice and snow. The people were warm and secure in their lodges which were covered and floored with buffalo hides. Smoke of the small cooking fires escaped from opened flaps at the peak of the lodges. After the long months of hunting and preparing for the winter, now families drew closer together. Children learned tribal traditions from stories told by the elders. Young girls helped their mother with the work, and boys dreamed of a coming spring when they might be allowed to join their fathers riding out to hunt.

Angry River; Overland Astorians 1811

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1978) | Image Size: 24”h x 48”w; Framed Size: 34 ½”h X 58 ¼” wpainting

One of John Clymer’s great talents as an artist was that he was also an excellent storyteller. He could take actual events in history and turn them into compelling visual stories, a testament to his many years spent as an illustrator for many leading magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post, Field and Stream, and Leatherneck. Here he creates an episode from a journey undertaken by a rugged and hard group of men who set out from St. Louis in 1811. These Overland Astorians were bound for the Oregon Coast to establish a fur trading post for the John Jacob Astor Company at the Columbia River mouth.

On their way up the Missouri River by boat, they met John Hoback, Jacob Reznor and Edward Robinson returning to St. Louis after a season of trapping in the Rocky Mountain region. They advised the party to abandon the proposed plan of following the Lewis and Clark route because of the hostiles they would surely encounter and agreed to act as guides over a more Southern route.

The party left the Missouri at the Arikara Villages and travelled overland through present day South Dakota and Wyoming. Crossing the Continental Divide at Union Pass, they proceeded across Teton Pass to the Snake River in Idaho. Here they left their horses, built dugout canoes and started down river.

“Angry River” shows the party on October 26, 1811, again travelling by boat much to the joy of the French-Canadian boatmen who were part of the group. The happiness was short lived, however, and the fate of these men is anticipated through the painting. Clymer illustrates the lead canoe just as it is about to plunge into rough, white water. The canoe’s prow is slightly raised giving a sense of movement to the scene, and a large boulder just to the left of the canoe further heightens the sense of danger and drama.

Once more afoot as winter approached without food, supplies and hundreds of miles from their intended destination, they faced a desperate situation.

Lewis & Clark in the Bitterroots

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1967) | Image Size: 30”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 41 ¼”h x 51 ¼”wpainting

In the Spring of 1804, Meriwether Lewis (b. Aug 18 1774) and William Clark (b. Aug 1 1770) embarked upon one of the grandest adventures in American History. For two years, four months and ten days they survived in the vast, unknown territory of the great West. They were co-leaders of the Corps of Discovery dispatched by President Thomas Jefferson to explore the unknown regions of the Louisiana Purchase; 800,000 square miles of land purchased from France for fifteen million dollars.

Lewis and Clark carefully chose thirty men to accompany them. The journey covered 7689 miles of the unknown wilderness. They were the trail blazers for the opening and settlement of the trans-Mississippi West. The self-reliance and perseverance of these men and that of Sacajawea, the lone woman who joined them in November of 1804, in the face of constant challenge, hardship and danger warrants a special place of honor in America’s History.

This painting gives us a sense of the desperate atmosphere that was frequently evident during the long journey. The scene is on September 16, 1805, as the party struggles across the Bitterroot Mountains in present day Idaho. The journals of the expedition relate their desperation. It had snowed all day. The Indian trail they had been following was covered, and it was increasingly difficult to find their way. Their journal recorded that “in many places we had nothing to guide us except the branches of the trees which, being low, have been rubbed by the burdens of the Indian horses”. Food supplies were about gone, game was scarce. They were cold, wet, hungry and dispirited.

And yet, these were individuals who were equal to the adversity they confronted. In a few weeks they would reach their ultimate goal of the Pacific. Even then, there was little time for relaxation. The return journey was still to be made.

The Fur Press

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1977) | Image Size: 30”h x 60”w; Framed Size: 41”h x 70”wpainting

The fur trading era was but a brief episode in the history of the early West. But it was the period when white men first ventured in any significant numbers beyond the pale of civilization to the wild country of the western mountains. Men who prized freedom and independence in its purest forms embraced the chance of a life away from the artificial restrains of the structured social order of the East.

Self-reliant men of rugged constitution wandered into the far West with long rifles, sharp knives and a set of steel animal traps. With little else, they made a life for themselves where every day became an adventure. Winters were spent in search of beaver. By day, traps were set and checked, the fresh catches were skinned and the pelts stretched to dry on willow hoop frames. At night, the men hovered around small fires in thrown-together shelters and dreamed of sunshine and springtime.

With the coming of spring, the trappers shed their heavy clothes and raised their faces to the warm sun. Here they have constructed a crude mechanical press to prepare the winter’s accumulation of beaver pelts for transportation. The dried pelts are removed from the willow frames folded and pressed into bundles. The bundles were then wrapped in the hides of deer or elk and tied with wet rawhide thongs. The rawhide would shrink as it dried, further compressing the bundles which could weight up to one hundred pounds.

Once the work was finished, the men would load the bundles on pack horses or primitive boats for the trip to the trading posts further down stream. If the winter’s catch had been a good one, the men were happy at the prospect of a celebration at the trading post. Already they contemplated where to set their traps during the next winter.

The Trade Boat

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1983) | Image Size: 30”h x 48”w; Frame Size: 40 ½”h x 58 ½”wpainting

By the mid-1830s, steamboats were navigating the Missouri River between St. Louis and Ft. Union more than 2000 miles to the west. This was the avenue of commerce for the fur trade. From Ft. Union, the trappers and traders outfitted and moved on up the Missouri and the Yellowstone in sturdy, flat-bottomed keelboats. Their destination was beaver country and the Indian villages closer to the headwaters of the western rivers.

This scene is of an American Fur Company trade boat out of Ft. Union that was bound for the more remote Ft. McKenzie. The boat was anchored mid-stream to trade with Indians for beaver pelts, furs, buffalo robes and fresh dried meat. The traders would not bring their boat to shore in case tensions arose.

The chiefs come aboard first to talk and receive presents from the traders. Then men and women eager to trade begin to swim out pulling their own trade materials in bullboats made from buffalo hides stretched over willow frames.

The white traders become concerned as more and more Indians approach and attempt to board the already crowded vessel. Heavily out-numbered, the crew hoists a crude sail and begins to move on upriver, forcing the Indians to disembark. They are told by the traders to go to Ft. McKenzie for further trade.

Clymer did a tremendous job in this oil painting conveying a sense of frenetic action as the group of traders find themselves overwhelmed by the number of Indians who wish to do business with them. In reality, such a situation would surely be chaotic and Clymer’s use of many different figures arriving from different angles at the boat shown in the center of the canvas underscores the nature of the Traders’ dilemma.

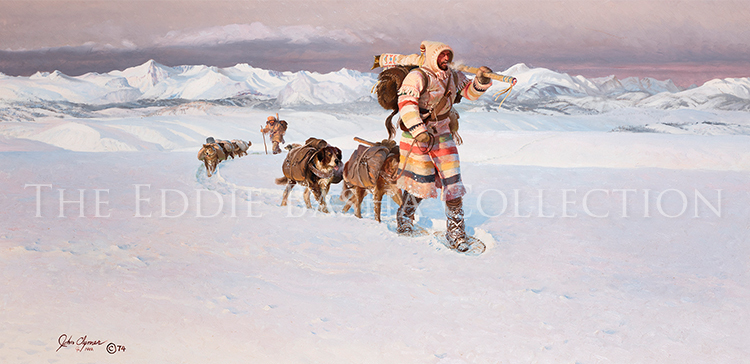

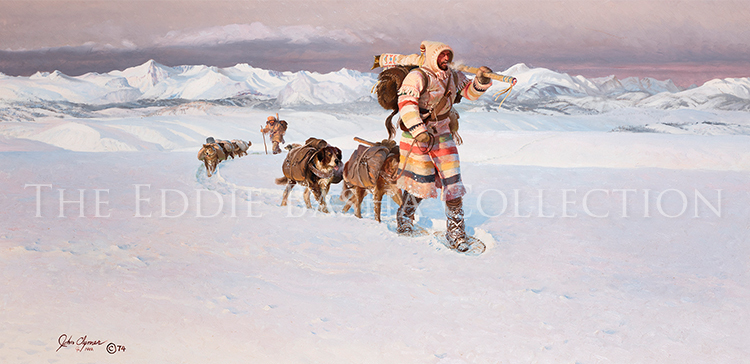

Winter Journey

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil | Image Size: 24”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 30”h x 50”wpainting

Life and death hung in the balance as the long season of cold winds and deep snow descended upon the far West. Trappers selected camp sites and began to set their traps along the high country streams and rivers. For these men it would be a long time until spring. The smaller outlying trading posts were abandoned as frontier merchants withdrew to the more substantial establishments further down river to the east.

In the autumn of 1829, the partners of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company had shipped the last of the year’s furs back down the river to St. Louis. Looking for diversion before the cold came down, Jedediah Smith, David Jackson and several other employees including Moses Harris set out on a fall hunt. Down in the Big Horn Basin country of northwest Wyoming, they met Milton Sublette and his party of trappers who were settling in close by the sulfurous river that the Indians called Stinking Water.

Winter was closing in and prospects for a good trapping season seemed excellent. The partners decided to send for supplies and trade goods in order to be ready when the trappers and Indians came together the next summer for the annual trading rendezvous across the mountains in the valley of the Green River.

On a bleak Christmas Day in 1829, William Sublette and Moses Harris set out on the long, cold overland trek to St. Louis. They travelled on snowshoes with a string of dogs to pack their provisions. Neither man ever recorded the hardships encountered on that epic winter journey. But they did reach St. Louis in time to see that the company’s trade goods were on the first boats up the Missouri as the ice began to thaw in the spring of 1830.

Night Guard

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1972) | Image Size: 20”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 31”h x 51”wpainting

The buffalo had been plentiful and the number of kills was high; so many that the skinning and butchering of the carcasses wasn’t completed by sundown. Night had come, but the moon did not rise. Drawn to the smell of blood and death, wolves approached boldly and coyotes howled from the low hilltops in the darkness.

As the weary hunters and their winded horses rested in camp, protecting the bounty fell to the women and children. Defiantly they stood, grouped around small fires through the long hours on both sides of midnight, snarling back at the predators that would attempt to steal what was not theirs. These were the brave women of the Crow people.

The hunting ground was in the upper Wind River Valley where the surrounding mountains blocked out the cold winter winds and attracted an abundance of game. It was a narrow valley, lined with natural passages between eroded rock formations where buffalo could be driven toward hunters waiting in the uneven breaks. The Crow hunted this special place for generations, ever grateful for the bountiful blessings. It was said that everything the people needed for a good life was provided by the buffalo, with the exception of water for drinking and lodge poles for the tepee.

History tends to record most often the daring exploits of the hunter and the warrior. Little is said of the valiant woman alone or with her children who stood watch on a long dark night when wild wolves roamed the Wind River Valley.

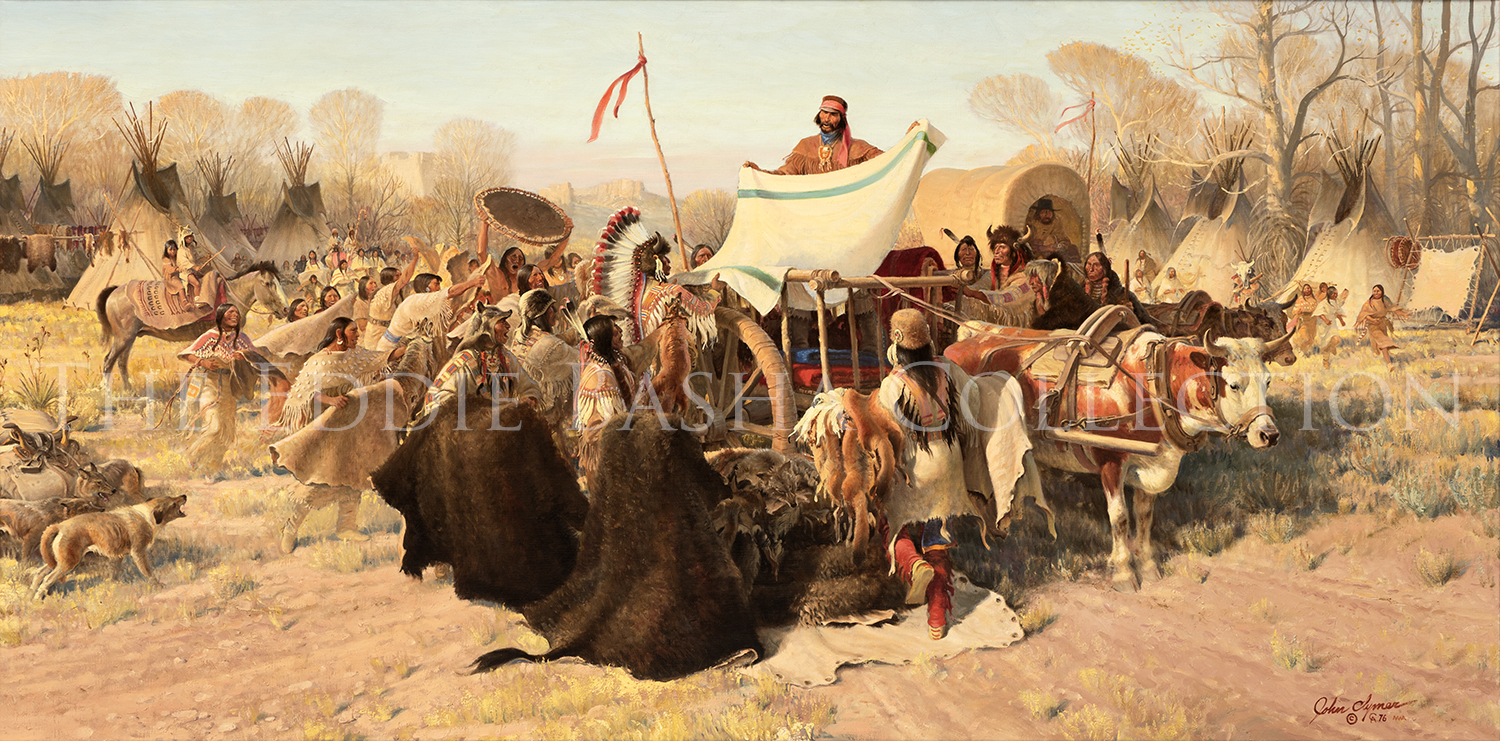

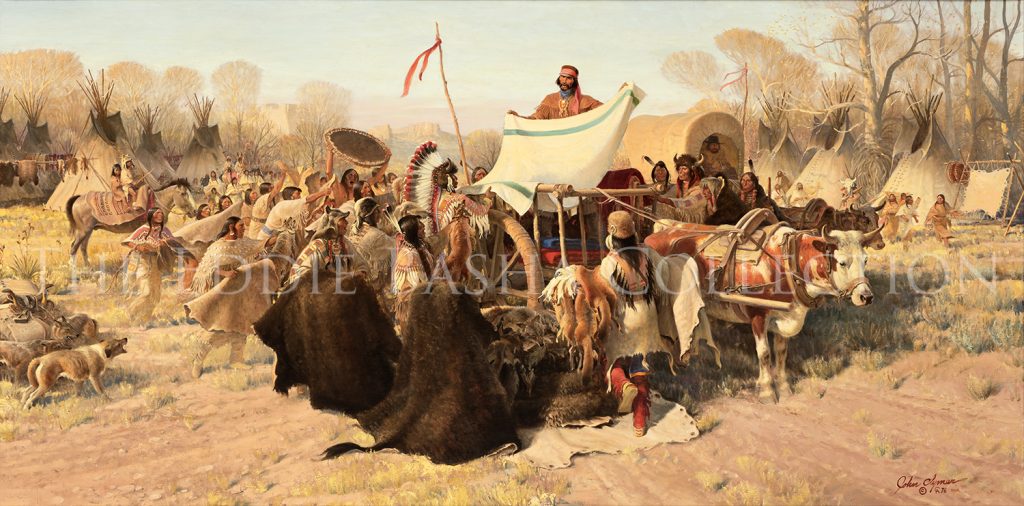

James Bordeaux: Trading with the Sioux, 1856

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1976) | Image Size: 30”h x 60”w; Framed Size: 41”h x 71”wpainting

Antagonism between the Indian and the White Man is a common thread throughout the history of the American West; even a casual purview of the relations of these two peoples reveal an abundance of conflict, confrontation and tragedy. Yet, there are notable exceptions to this shadow over the Old West.

There were men who came as friends and were able to live at peace with the Indian. One of these men was the independent trader, James Bordeaux. In 1856, when many bands of the Sioux left Fort Laramie and Major Twist, the Indian agent, moved the agency away from the Fort, James Bordeaux went among the Brule Sioux on the White River with his Red River carts to trade.

Bordeaux was married to the daughter of the Chief of the Brule. His interest in the Sioux people went much deeper than the considerations of commerce. He found the Sioux way of life to be in harmony with creation; a quality already lacking among the whites as they sought to subdue nature and turn it to their own purpose. This unusual man considered the Sioux as his friends. He conducted himself as a guest in their camps and dealt with them fairly in his business at their camps and at his trading posts.

The name of James Bordeaux is not as familiar as are those of the white men who made their reputations as Indian fighters. We can only speculate about the course of history had there been more men like James Bordeaux in the vanguard as white civilization pushed into the land of the Indian in the early West.

Narcissa Whitman Meets the Horribles – July 1836

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1971) | Image Size: 24”h x 48”w; Framed Size: 34”h x 58”wpainting

Two women stand out prominently in the early history of the American Northwest. The first is the Indian women, Sacajawea, who accompanied the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The second was Narcissa Whitman.

In 1836, Narcissa Whitman joined her doctor-missionary husband, Marcus, and another missionary family for the grueling overland trek from St. Louis to Fort Walla Walla, Washington. At the Loup Fork of the Platte, the party joined a fur caravan under the command of the rough frontiersman, Broken Hand Fitzpatrick. The fur caravan and the missionaries headed west for the trappers’ rendezvous on the Green River. Word had reached the rendezvous that white women were in the approaching caravan. This painting depicts the welcoming committee which was dispatched to escort Narcissa and the party to the rendezvous site. Half a dozen Indian tribes were represented that year on Green River, along with four hundred white trappers. It was a time for getting drunk and trading furs for the coming winter. The Whitman party was at the rendezvous for twelve days. During this time, they passed out “all the Bibles that could be carried on two stout mules.” The wild, free trappers were awkward, but respectful to both Narcissa and the other lady with the party, Eliza Spalding. Narcissa was delighted with their attendance to morning and evening devotions. “This is a case worth living for,” Narcissa wrote in her diary.

From Green River, the trip turned into one of extreme hardship. Food became scarce and the mountain country made the travel by wagon almost impossible. Finally, on September 1, 1836, after six and a half months travel, the party reached Fort Walla Walla.

This was the first time wagons had been used on the upper reaches of the Oregon Trail. Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding were the first white women to cross the Continental Divide. It set the stage for the hundreds of families and wagons that were to follow soon along the traces of the Oregon Trail. The way had been shown and the settling of the far West could begin in earnest.

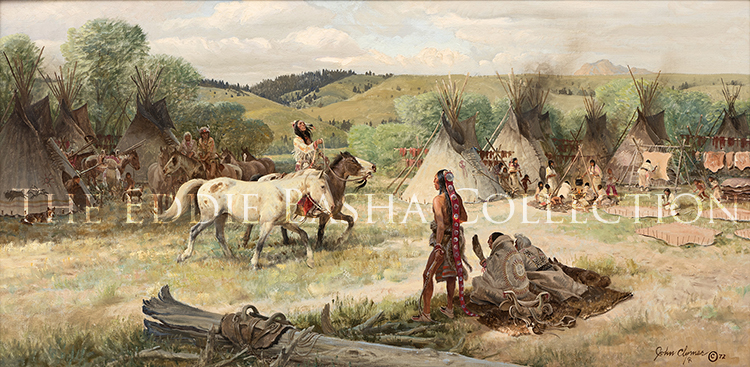

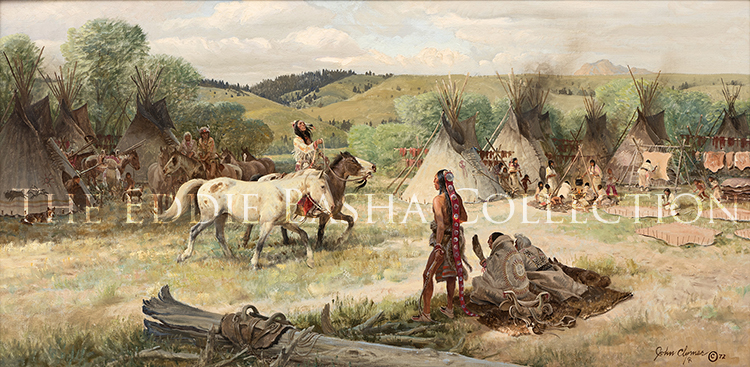

Breaking Wild Horses

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil | Image Size: 24”h x 36”w; Framed Size: 35”h x 46”wpainting

Horses were essential to the survival of the American Indian tribes that wandered across the high plains of the West. They were used in hunting, warfare and simply moving camps from place to place. It was essential that animals were well trained and that they quickly became accustomed to the presence of a rider on their back. John Clymer’s “Breaking Wild Horses” is a dramatic scene pulled directly out of the history of the Plains Indians. It is an accurate and exciting recreation of one of the methods used to break wild horses.

Here, two men riding double on a trained horse led the bronc by rope or halter into the water. When the water reached the horse’s shoulders, the front rider took hold of the lead rope near the bronc’s chin while the other rider quickly jumped on its back. As soon as the second rider was positioned well, the front rider on the trained horse let go of the rope. And as the bronc jumped and bucked, his head got wet and he would begin to quiet down. When sufficiently tired, the second rider could ride the bronc out of the water. If not sufficiently broken, the bronc could be led back into the waters and the process repeated until he was subdued.

Clymer used two compositional devices effectively to focus the viewer’s attention on the primary action. Viewers are not only drawn into the scene and feel the intensity of movement and drama, but they also learn a great deal about how the Plains Indians trained these essential animals.

Fur Flotilla

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1974) | Image Size: 20”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 30 ¼”h x 50 ¼”wpainting

In the past, many people connected the opening of the West with wagon trains, long lines of canvas covered prairie schooners stretched out across the horizon, transporting people and freight into a new and distant land. Little thought was given to the men on small boats who fought their way three thousand miles up the Missouri River, from St. Louis to Ft. Benton, and then back down again.

It was the fur trade which first lured significant numbers of men into the West. The demand was great enough to promise healthy profits if the furs could be delivered to the markets at settlements like St. Louis. But plentiful beaver and the fox could only be found three thousand miles away along the streams that ran down the slopes of the Rocky Mountains. Small parties of trappers could not pack in sufficient supplies or pack out enough furs to make the enterprise profitable when so much time was demanded for travel.

The Missouri River became the avenue of the fur trade in the 1830s. Steamboats could navigate from St. Louis on the Mississippi to the mouth of the Missouri, then up the Missouri to Fort Union and the mouth of the far Yellowstone. Here supplies were unloaded and furs taken on for the return voyage.

Trappers outfitted and sold their furs at Ft. Union and then set out in the smaller Mackinaw boats. The Mackinaws could navigate the shallow waters of the Yellowstone carrying the trappers and their cargoes to and from the headwaters of the Missouri and Yellowstone further to the West. The flat-bottomed Mackinaws were built on the spot by the resourceful trappers; up to seventy foot-long planks hewn from the Montana forests. Rough men with crude boats on wild water carried American commerce into the most remote regions of the early West.

Moccasin Trail

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1982) | Image Size: 30”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 40 ½”h x 50 ½”wpainting

The Nez Perce were fortunate in the early days to live on good land with abundant food sources. Permanent villages located along the rivers and tributary streams were fish plentiful. After the spring floods, the salmon came to spawn and filled the rivers and streams. The annual salmon run furnished fish, properly preserved, for the whole year. Many edible plants also grew in the moist climate and multiple camas meadows furnished another important staple, the camas bulb. (Camas – a lily family genus chiefly of the Western U.S. with edible bulbs). From early June to late fall, wild berries of various kinds furnished tasty additions to their regular diet. The surplus berries were pressed into cakes and dried for winter use. The men did the fishing and hunting. The women prepared the fish for smoking and drying, and gathered the roots and wild berries in tightly woven cedar bark baskets.

There were several trails leading out of the sheltered land. The Old Nez Perce Trail or LoLo Trail was the northernmost which would, for many miles, cross the crest of the ridges of the Bitterroot Mountains to the Bitterroot Valley. It was travelled afoot long before the Indians acquired horses. It was much easier to follow the ridges from one meadow to another than to follow the narrow river gorge or traverse the steep rugged, pine clad mountains. The meadows in the midst of this heavily forested land also provided berries and roots for the travelers on the trail.

In this painting, a party of Nez Perce Indian women and children are traveling the old trail on a berry picking expedition. At this time, they had only dogs to help carry their burdens. Some of the women are wearing basket-woven hats, typical of the women of the northern plateau region.

Alouette

Artist: John Ford Clymer, CA (1907-1989)

Description: Oil (1974) | Image Size: 30”h x 60”w; Framed Size: 41”h x70”wpainting

The trappers who sought fur treasures in the Northwest wilderness were men of abundant vitality and gusto. The lives they led were unbelievably arduous and isolating. The work was demanding and the environmental dangers were plentiful; bad weather, wild animals and hostiles. And though there were few occasions when opportunity for relaxation arose, the trappers fully embraced them.

One such occasion was in the middle of the relentless Northwestern winter when Rocky Mountain weather made trapping impossible. A fur brigade working a particular region assembled a winter camp in a sheltered spot. It was then the men could relax and enjoy the camaraderie. Throughout the day the camp bustled with activity. Hunters came and went, wild game was butchered and prepared, repairs were made to clothing, arms and equipment, and shooting and wrestling matches abounded.