David Halbach, CA

(1931-2022)

In 1985, David Halbach was inducted into the Cowboy Artists of America, the same year his painting Chippawa Hunter won the Purchase Award at the Buffalo Bill Historical Museum in Cody, Wyoming. The year 1986 marked his first place award for Region 11 in the Arts for the Parks competition. David was honored in 1990 with the Western Heritage Award given by the Favell Museum of Klamath Falls, Oregon, for excellence in portraying the West, past and present, in watercolors. His painting Heading Out appears in The West, A Treasure of Art and Literature by Watkins & Watkins.

A graduate of Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles, David worked on Lady and the Tramp feature Disney film, taught art in the Los Angeles Unified School District and joined other artists in many invitational art shows and galleries. On his first invitation to the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, he won the prestigious Silver Medal for his watercolor, Story Teller.

In 1995 David was contacted by National Geographic to help complete a film project for children. His paintings were used to depict the life of mountain men. In the summer of 2004, the U.S. Embassy asked to show one of David’s paintings in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, with the Arts in the Embassies Program, and his painting Forewarned was purchased by the Museum of Western Art in Kerrville, Texas. In 2006, David was selected as one of the top 100 artists in the 2006 Arts for the Parks Show in Jackson, Wyoming.

During the past 18 years, David has won numerous CAA Gold and Silver medals. In 2010 he won the Gold Medal for Water Solubles for his painting Awaitin’ The Cow Boss.

Source: Cowboy Artists of America

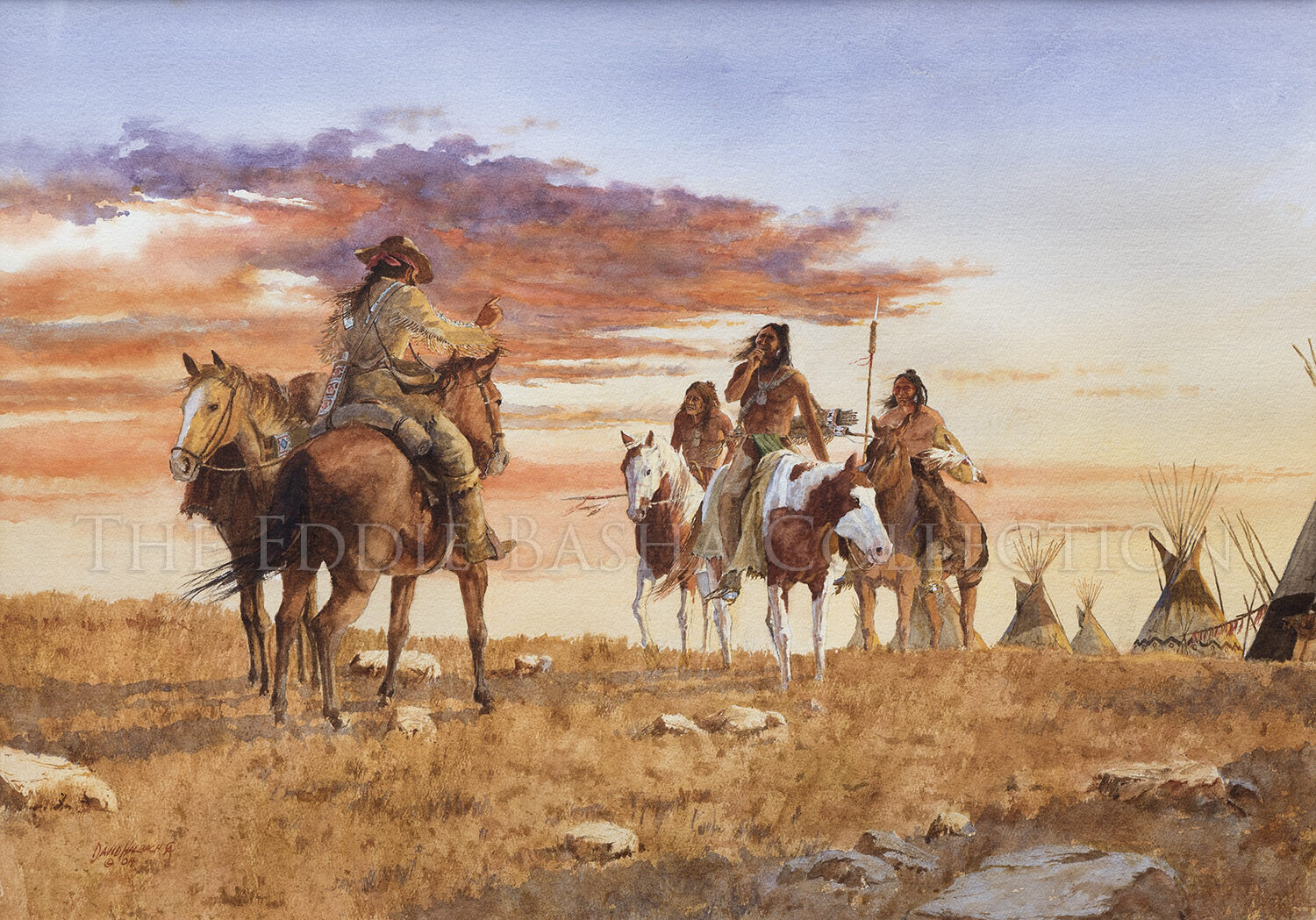

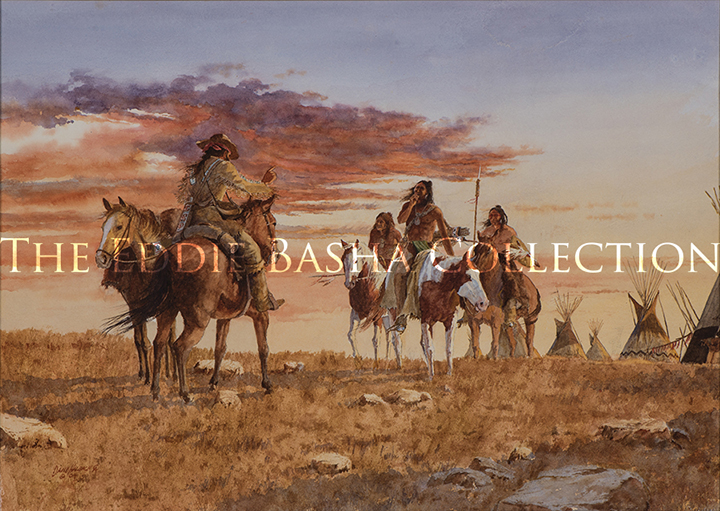

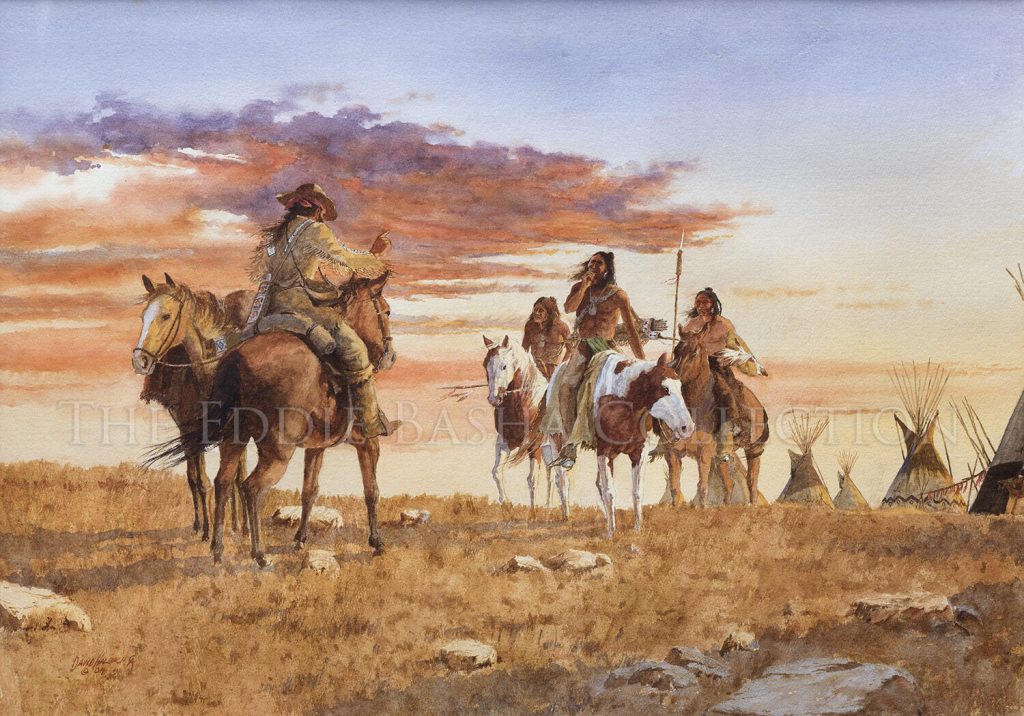

When Talk Fails

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Description: Watercolor (2004) | Image Size: 21 ½”h x 29 ½”w; Framed Size: 36 ¼”h x 44 7/8”wpainting

Set beneath the rapidly diminishing colors of a fading sunset, this scene from the frontier presents a lone trapper and group of Indians attempting to communicate. Failing to understand one another through spoken words, the group uses expressions and hand signals to get their points across. The figures are framed on one side by a group of teepees and on the other by the sunset lit clouds. The action of the painting is fixed between those two anchors prompting the viewer to speculate on just what messages are being communicated. While the focus of the painting is clearly the group of figures, the background of a rocky landscape and the multicolored clouds add another layer of drama to the scene.

Cowboy Artist of America Member, David Halbach, was masterful in his selection of portraying unique perspectives of the old west an equally masterful working in his favorite medium, watercolor. “When Talk Fails” made its debut at the 39th Annual Cowboy Artists of America Exhibition & Sale, Phoenix Art Museum, October 2004.

Snake Priests (Hopi)

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Description: Watercolor (1987) | Image Size: 16”h x 14”w; Framed Size: 26 ½”h x 23 7/16wpainting

This David Halbach watercolor gives the viewer a dramatic insight into the heart of one of the Hopi People’s most important ceremonies, the Snake Dance. Here, several priests are seen in a kiva about to ascend by ladder into the village. Sunlight pours in from the kiva opening above them and reveals the many accouterments and preparatory elements of the ceremony. The painting's striking vertical composition accentuates the action unfolding. Of all Halbach’s many depictions of the Snake Dance, this is one of his most theatrical.

Hudson Bay Trappers

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Description: Watercolor (1995) | Image Size: 14”h x 22”w; Framed Size: 23”h x 31 3/4”wpainting

David Halbach is a versatile watercolorist who is adept at painting many different subjects from the American West, both historical subjects and contemporary scenes. Here, he focuses his attention on a scene from the fur trade era—a trapper and his Indian guide are setting out by canoe on a fog shrouded waterway. In the far distance, barely visible in the fog is the faint outline of another canoe. The two figures in the canoe are depicted in detail with the trapper clad in a white shirt that focuses the viewer’s attention on the center of the painting and guides his eye toward the front of the canoe and beyond into the haze. Halbach places his viewers into the scene and at the beginning of a journey whose outcome has not been determined. The scene is just the beginning of a story from this particular era. The overall effect is an atmosphere of anticipation.

“Hudson Bay Trappers” was depicted in the book entitled “Cowboy Artists of America” authored by Michael Duty and published by the Greenwich Workshop Inc. in 2002. It was also featured at the Phippen Museum (Prescott, AZ) exhibition, “Cool, Cool Water” in 2018.

Antelope Priests

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Description: Watercolor (1986) | Image Size: 10”h x 16”w ; Framed Size: 20 ½”h x 25 ¼”wpainting

Returning to one of his favorite subjects,

Cowboy Artists of America Member David Halbach depicts in “Antelope Priests”

the beginning of an important Hopi ceremony, the Snake Dance. He has presented the ceremony in many paintings with each painting showing a different facet of the cultural custom. Here the priests emerge through an adobe portico as they proceed to the beginning

of the ceremony. Halbach uses one of his most effective motifs to spotlight the movement of the priests, the transition from darkness to light. Here he uses sunlight to focus attention on the priests while much of their surroundings are shown in deep shadow.

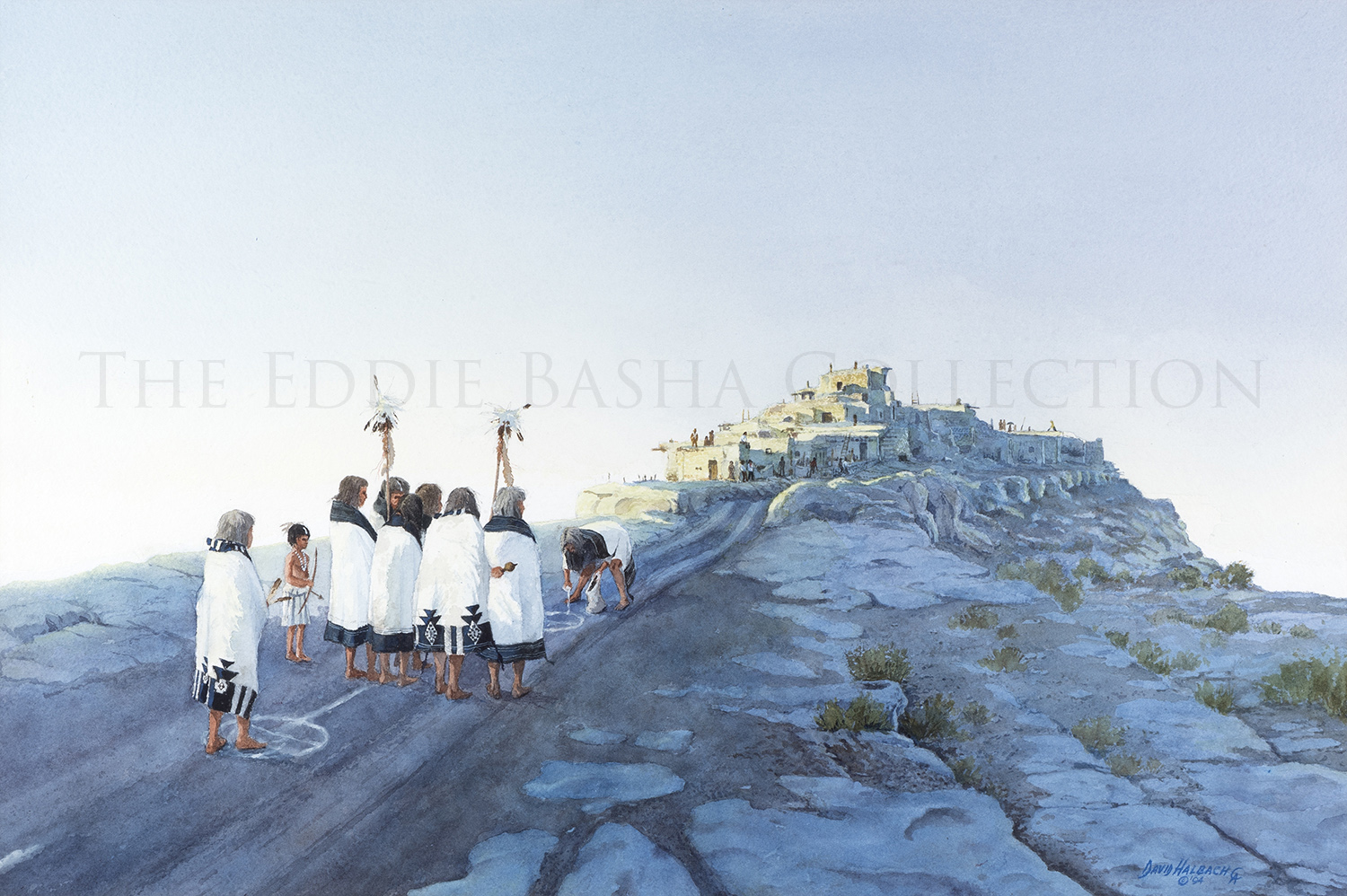

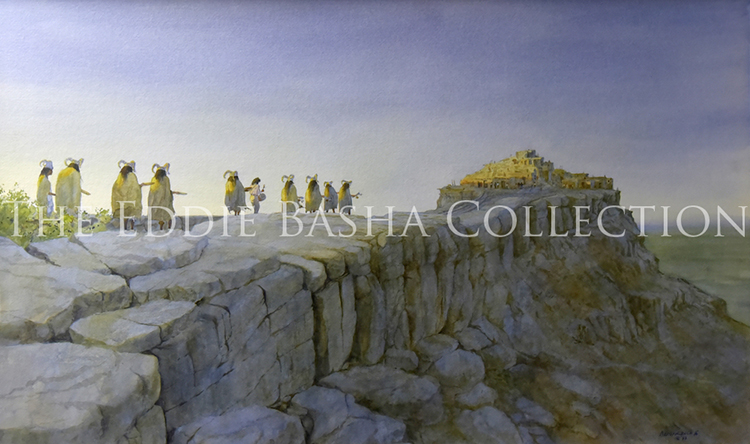

Powamu Ceremony

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Description: Watercolor (1998) | Image Size: 20”h x 30”w; Framed Size: 31”h x 41 ½”wpainting

One of the most important Hopi ceremonies is the Powamu Ceremony, or Bean Ceremony, which typically occurs during February. The Powamu is much anticipated as it is designed to promote fertility and germination for the upcoming growing season. Hopi males already initiated are expected to begin the germination process by planting seeds in the kivas and these seedlings along with ceremonial bundles are interpreted as offerings as well as omens for a successful growing season during the ceremony. The Muyˊingwa or two-horned katsina, the deity of germination, presides over the ceremony. The Powamu Ceremony is not always singular in nature, but rather can be entwined with other ceremonials such as the initiation of tribal youth into the Powamu and Katsina Societies that typical occur every three to four years.

Cowboy Artist of America member, David Halbach, had great respect for and a keen interest in the religious ceremonies of the indigenous people of the Southwest. His depictions of Hopi ceremonials, such as this one, offer an insight into customs that few outsiders are privileged to see. Here ceremonial participants are shown in authentic, detailed katsina garb in front of a Hopi pueblo structure. Villagers are shown viewing the ceremony from various vantage points atop the dwellings and on the ground. Daybreak provides the primary light source and bathes the dancers in a cool white light that offers a contrast to the dark blue of the morning sky and the beige of the adobe. The main watercolor focus is on the ceremonial participants in the middle foreground.

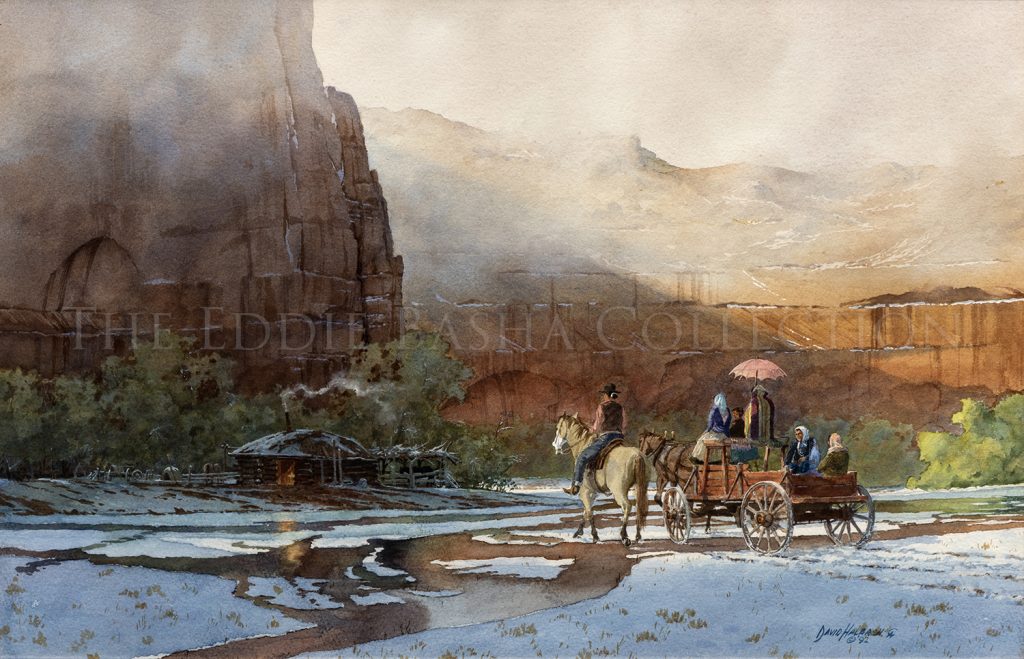

Pink Parasol

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Description: Watercolor (1992) | Image Size: 16”h x 24 ½”w; Framed Size: 26 3/8”h X 35”wpainting

The pink parasol provides a surprising focal point drawing the viewer’s eye into the journey and toward the group of Navajo travelers making its way on a lightly snow-covered landscape toward a hogan situated at the base of a steep canyon wall. Above the parasol the misty white cloud will soon burn away in the developing sunlight. David Halbach leaves the exact details of his story to the imagination of the viewer. Are the travelers visitors or are they returning home? Either way, a warming fire awaits their arrival. In this watercolor Halbach reveals a keen eye for the beauty and nuances of the atmospheric landscape and the narrative flair of an accomplished storyteller.

“Pink Parasol” won the water soluble silver medal at the 27th Annual Cowboy Artists of America Exhibition & Sale held at the Phoenix Art Museum in 1992. It was subsequently loaned to Western Spirit Scottsdale’s Museum of the West for its “A Salute to Cowboy Artists of America and a Patron, the late Eddie Basha: 50 Years of Amazing Contributions to the American West” Exhibition (November 2015-May 2016).

Jail Break

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Description: Watercolor | Image Size: 9”h x 17”w; Framed Size: 15 ½”h x 24”wpainting

In this scene of modern day ranch life, David Halbach covers most of his canvas with a snow-covered landscape surrounding the weathered barn and the washed out sky of a winter’s day. Such a stark backdrop allows him to rivet our attention on the cowboy roping the fleeing calf. The cowboy and calf run toward the viewer and are caught mid-action. Behind them, the gray boards of the barn depict a structure that has seen many winters. By depicting the sky and landscape with a minimum of detail, Halbach is able to convey a sense of the isolation of the scene and to highlight the narrative that is unfolding.

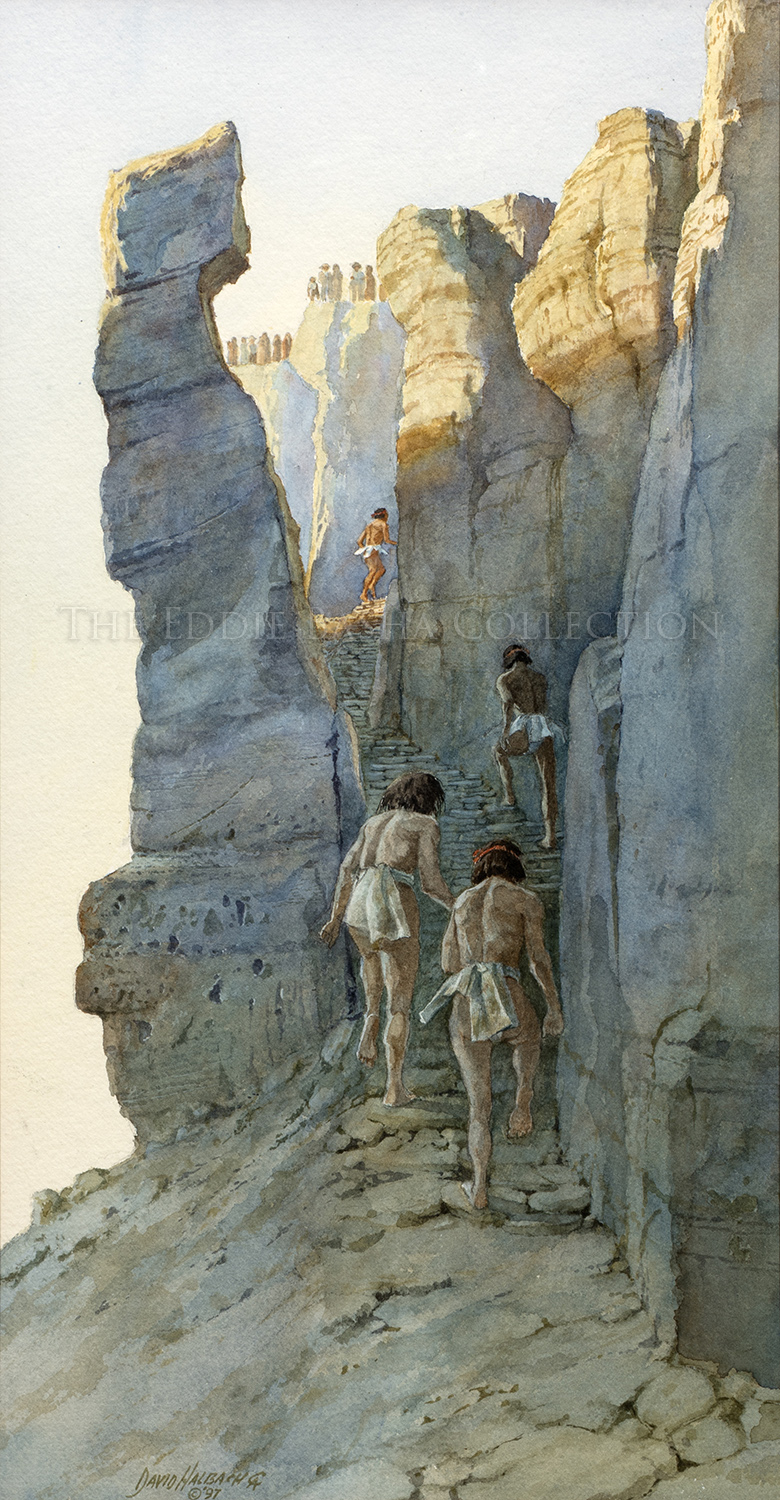

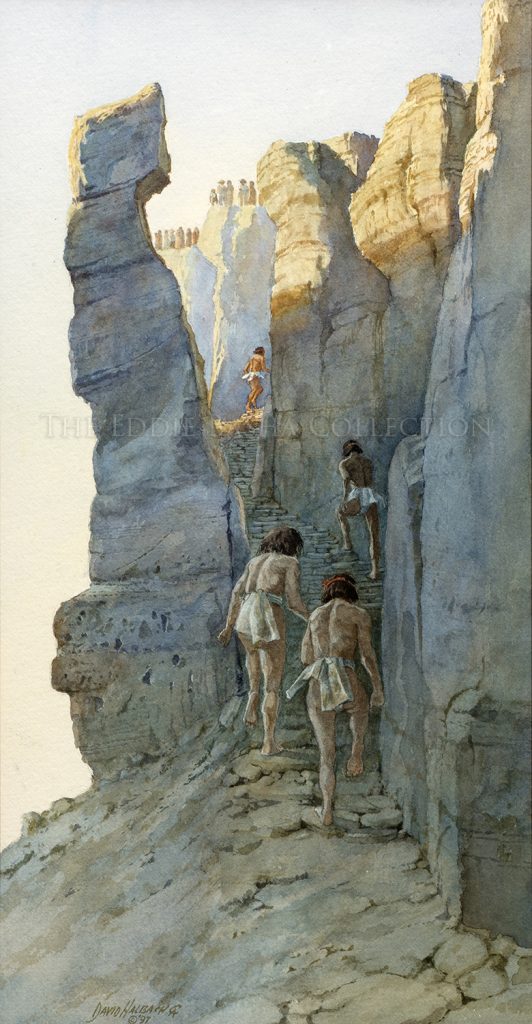

The Antelope Ceremony Begins

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Description: Watercolor (1997) | Image Size: 21”h x 11”w; Framed Size: 1 9/16”h x 21 ½”wpainting

In this watercolor, David Halbach effectively uses a vertical format to depict the steep canyon walls where a narrow set of stairs has been carved from the stone surroundings. American Indian figures are shown making their way up the stairs in the foreground, the middle distance, and the back ground. Several more figures are seen at the distant top of the canyon walls. By placing his figures in groups, Halbach gives the viewer the illusion of continuing movement as the participants of the ceremony make their way up the passageway. His subjects move from deep shadows at the canyon floor to bright sunlight at the very top. The contrast between the darkness and cool colors of the shadows and the bright sunlight and warmer tones of the upper canyon walls is quite dramatic.

“The Antelope Ceremony Begins” made its debut at the 1997 Cowboy Artists of America exhibition held at the Phoenix Art Museum.

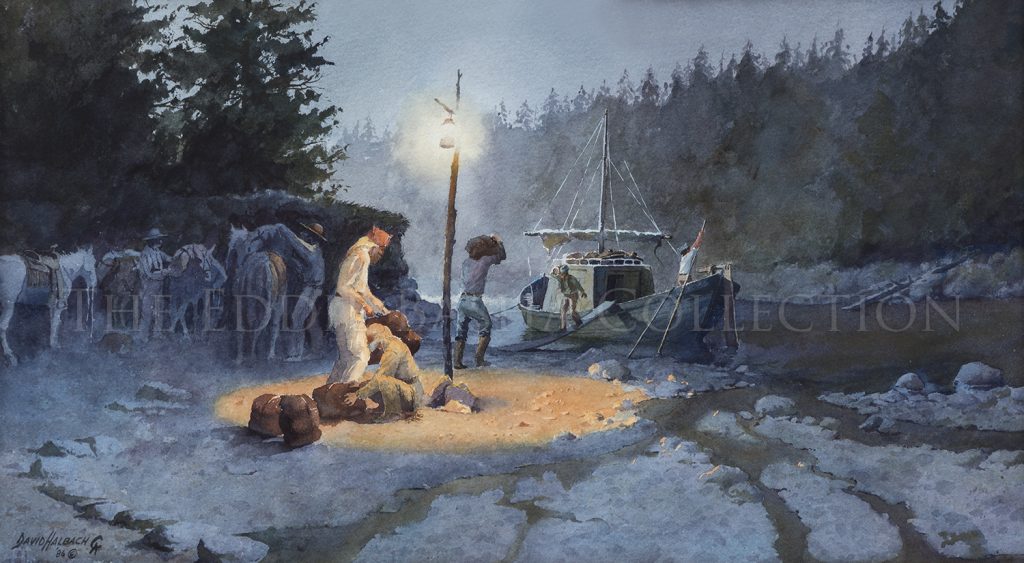

Pelts for Provisions

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Description: Watercolor (1986) | Image Size: 12”h x 21”w; Framed Size: 22 ¾”h x 31 ¾”wpainting

David Halbach uses a circular motif to tell this story from the fur trade era of the American West. A lantern on a pole placed in the center of the painting radiates a bright circle of light where two trappers are sorting pelts. Beyond them in the darkness, Halbach, still maintaining a circular composition, arranges other trappers and their horses on the top left arc of the circle and a trade boat being loaded on the top right arc. The contrast between the bright light of the lantern and the darkness of the surrounding landscape is quite effective in telling the story of “Pelts for Provisions” that adds a dramatic touch to the scene.

Territorial Omen

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Description: Watercolor | Image Size: 16”h x 28”w; Framed Size: 26 ½”h x 38”wpainting

As the subjects head through the shaded bend of the canyon wall, one of the riders alerts his companions by pointing towards the “omen” that presents just beyond on the other side of the shoreline ... a coup stick delineating “territorial” rights of another tribe. The sunlight in that area seems to be more absorbed than reflected by the stream projecting an aura of drama to the scene unfolding.

One of the more difficult tasks faced by a painter, particularly a watercolorist, is to effectively juxtapose very different textures such as the hard and craggy surface of a canyon wall and the reflective nature of standing water. In “Territorial Omen,” Halbach is able to achieve that juxtaposition in a highly authentic way. His water has a realistic shimmer and his canyon wall has a depth that makes one want to touch it. He also masterfully contrasts dark and light spaces to assist in casting the potential for an element of danger.

First appearing at the 31st Annual Cowboy Artists of America Exhibition & Sale in 1996 at the Phoenix Art Museum, Halbach’s “Territorial Omen” was more recently loaned to the Phippen Museum in Prescott, Arizona, for the “Cool, Cool Water” exhibition in 2018. It remains a permanent part of the EBC.

Flute Ceremony

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Description: Watercolor (1994) | Image Size: 15 ½”h x 24 ¾”w; Framed Size: 25 3/8”h x 33 3/8”wpainting

The Flute Ceremony traditionally held in August and on opposite years of the Snake Dance is a nine-day celebration encouraging rain and a successful corn crop and for the continuity of life after death. During the days leading up to the ceremony, an altar is constructed with carvings and paintings to represent the clouds that will bring rain to the villages.

The Flute Ceremony begins with a procession through the village. The clan chief leads a group that includes the flute boy, flute girls, men carrying cornstalks and warriors with bullroarers. Prayers for rain are said and a priest scatters corn meal on the ground before the flute altar. Water is poured into a bowl from all directions to symbolize the rain clouds and a bullroarer is used to represent the sound of thunder.

The unwrapping of the tiponi occurs on the sixth day of celebration. The tiponi is made of wood, shaped like a cup and decorated with rain cloud and corn symbols. Inside the cup rests a single ear of corn or corn grains. This corn represents the seed that was carried by the early tribes throughout their migrations. Wrapped in cotton string and feathers, the tiponi is unwrapped by a flute priest so the corn within can be planted. A new ear of corn is then placed within it and re-wrapped until the following year.

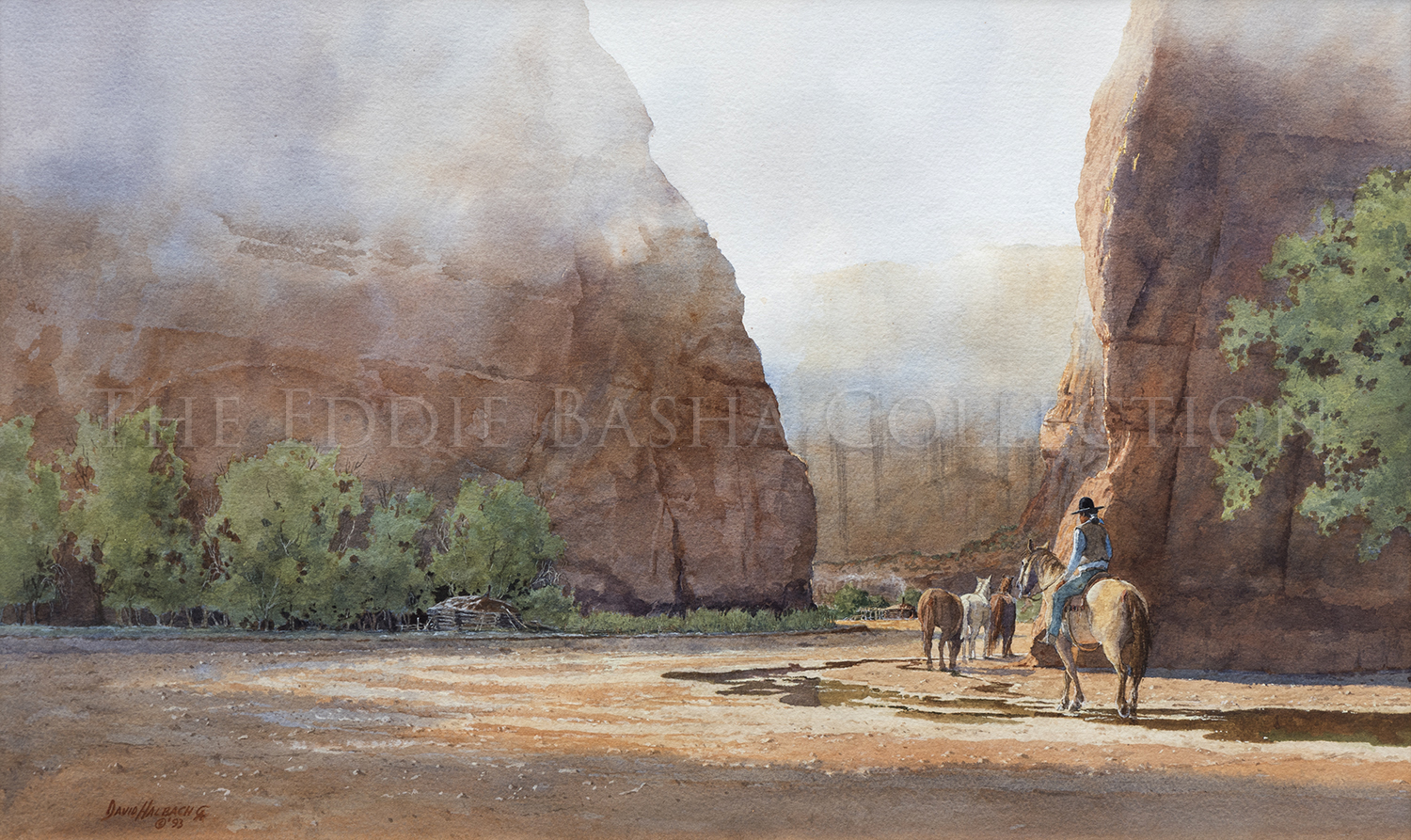

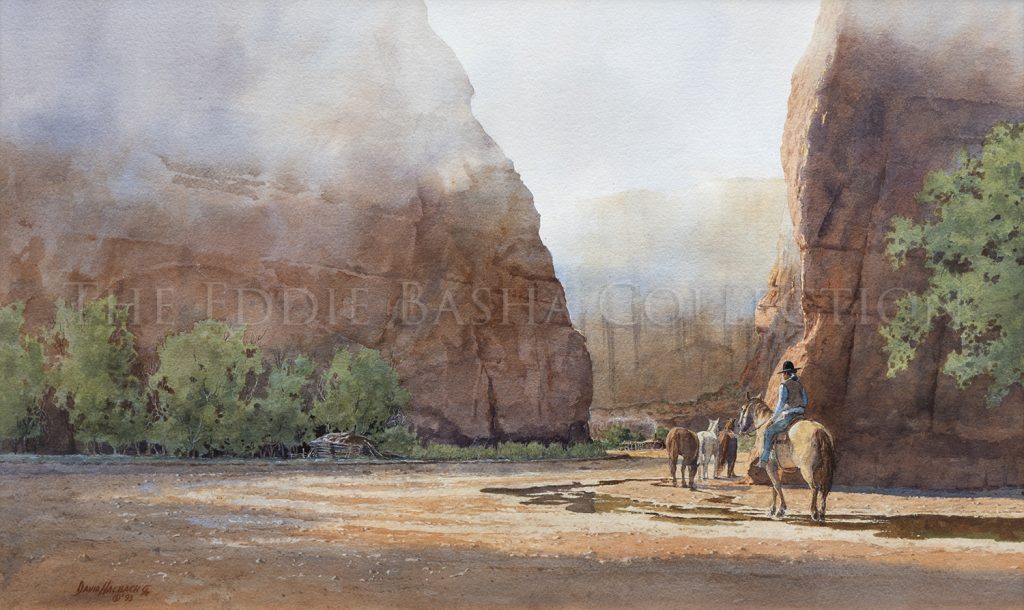

Canyon de Chelly Gold

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Description: Watercolor (1993) | Image Size: 15”h x 24 3/4”w; Frame Size: 27 1/6”h x 36 ¾”wpainting

David Halbach has a well-deserved reputation as a visual historian of the western frontier, an excellent storyteller, and a devoted student of American Indian customs and culture. With such a wealth of talents, his prowess as a landscape painter is sometimes overlooked. “Canyon de Chelly Gold” is primarily a landscape painting. It does include figures, a rider trailing three horses toward the mouth of a canyon, but the subject of the painting is the land with its sheer reddish canyon walls that are somewhat shrouded by white mists. The viewer’s eye is led into the heart of the picture by the figures which proceed from the right foreground between the two canyon walls. The green leaves of two groves of trees add a contrasting note of color to the rock faces of the canyon, and nestled beneath one of the groves is a traditional Navajo hogan. The path between the two prominent canyon walls leads into the distance toward another wall which gives the painting a sense of depth and grandeur.

The National Park Service website says the following about Canyon de Chelly National Monument: “It is a vast park in northeastern Arizona on Navajo tribal lands. Its prominent features include Spider Rock spire, about 800-feet tall, and towering sandstone cliffs surrounding a verdant canyon. Inhabited by several Native American peoples for millennia, the area is dotted with prehistoric rock art. The White House Ruins and Mummy Cave are remains of ancient Pueblo villages.”

Warnings and Portents

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Description: Watercolor on Paper (1998) | Image Size: 22”h x 18”w; Framed Size: 31 ½”h x 27”wpainting

“Warnings and Portents” is an excellent example of David Halbach’s skill as an artist and storyteller. A fur trapper is crouching near a stream to fill his canteen. Halbach portrays him just at the moment that he looks up, perhaps because of an echoing canyon noise, to see a shadow cast of an approaching warrior on the rock face. We are caught in a moment filled with alarm and anticipation—just as the trapper is.

Halbach’s use of light and shadow to set the stage for the unfolding drama is a key element of the painting. He has neatly bisected the painting; the top half in bright sunlight shows the steep and rough canyon walls with the shadow of the approaching warrior. The deeply shadowed bottom half almost obscures the figure of the trapper. As a result, the viewer must concentrate to take in all the aspects of the scene from the exquisite landscape to the details of the trapper’s clothing and his accoutrements, a rifle in one hand and a canteen in the other, and the trapper poised to take whatever action will be necessary. And it is those rich features that Halbach has left not only the outcome of the story to the imagination of the viewer, but for the viewer wanting more.

This piece won the silver medal in the water soluble category at the 33rd Annual Cowboy Artists of America Show & Sale in 1998 at the Phoenix Art Museum.

Fire that Talks

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Description: Watercolor | Image Size: 16”h x 24”w; Framed Size: 25”h x 32 7/8”wpainting

In “Fire that Talks,” Halbach isolates Indians on a vast plain who are using smoke from a small fire to send a message to distant comrades. The Indians are shown in the center of the canvas in full light, but shadows indicate that daylight will soon be waning, making signals such as this one impossible. The white puff of smoke emanating from the fire in the very center of the painting captures the viewer’s attention and immerses him in the unfolding story.

“Fire that Talks” made its debut at the Cowboy Artists of America Silver Anniversary Exhibit at The Museum of Western Art in Kerrville, Texas (April-September 1990) and later that same year at the 25th Silver Anniversary Exhibition & Sale held at the Phoenix Art Museum (October-November 1990).

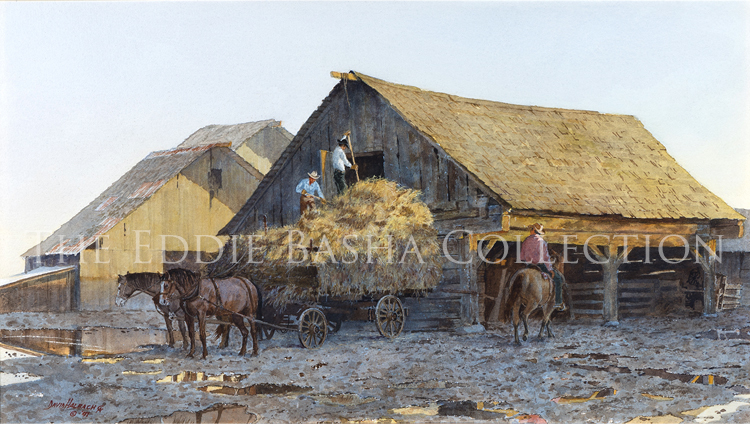

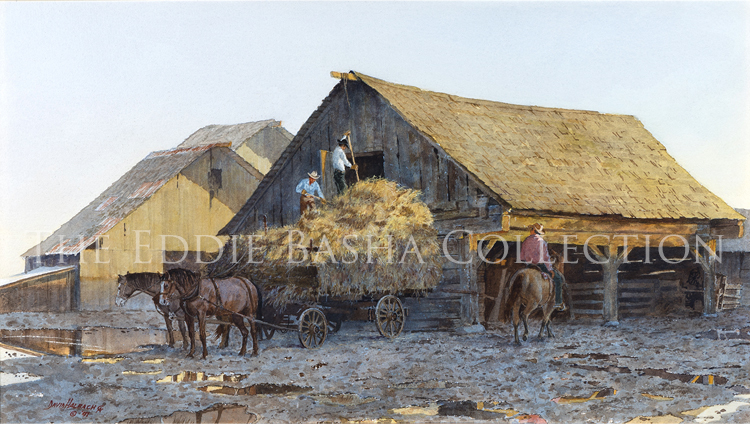

Just Makin’ It

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Description: Watercolor (1997) | Image Size: 13”h x 23 ½”w; Framed Size: 22”h x 32”wpainting

“Just Makin’ It” took home the Silver Medal in water solubles at the 32nd Annual CAA Exhibition & Sale at the Phoenix Art Museum in 1997. Dave Halbach masterfully captured the reflective quality of water and easily combined other textures such as the weathered wood of the barn and wagon, the horses’ coats, and that of the hay. The painting though executed in muted colors, has quite distinct scene details. Halbach effectively presented a narrative that is representative of just one of the many arduous and necessary tasks of ranching.

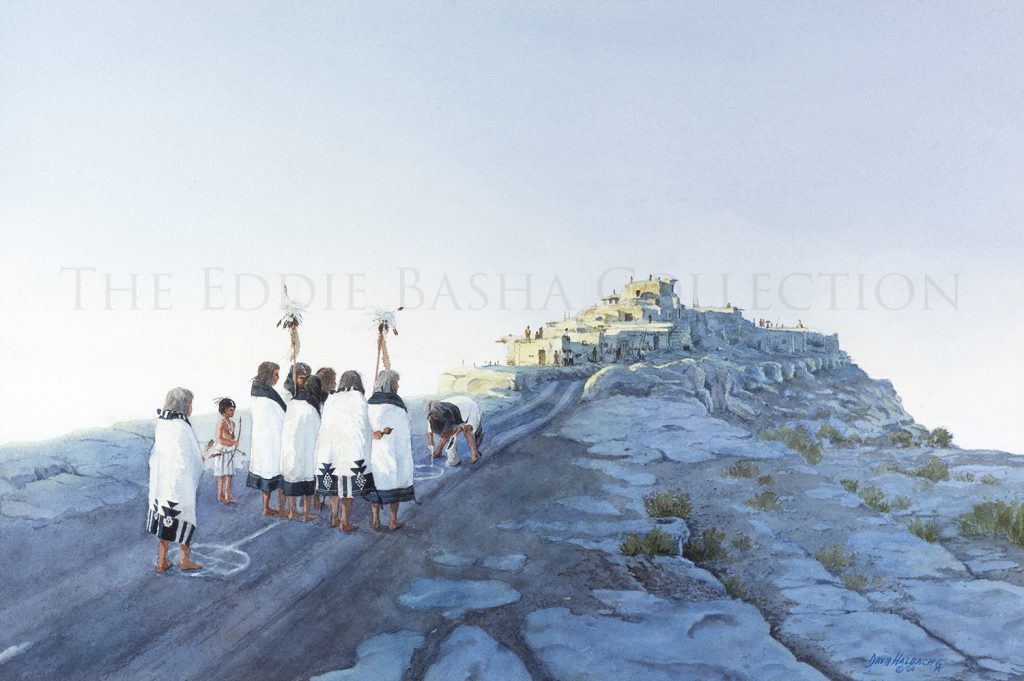

Evoking Clouds - The Snake-Antelope Ceremony - Mishongnovi

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Description: Watercolor | Image Size: 12”h x 16”w; Framed Size: 18 ¾”h X 22 ¾”wpainting

The Hopi Snake Antelope Ceremony is the grand finale of ceremonies to pray for rain. The ceremonies, conducted by the Snake and Antelope fraternities, last 16 days. On the 11th day, preparations start for the Snake Dance. For four days, snake priests go out from their village to gather snakes. On the 15th day, a race is run, signifying rain gods brining water to the village. Then the Antelope build a kisi, a shallow pit covered with a board to represent the entrance to the underworld. At sunset on the 15th day, the Snake and Antelope dancers dance around the plaza, stamping on the kisi board and shaking rattles to simulate the sounds of thunder and rain. The Antelope priest dances with green vines around his neck and his mouth, just as the Snake priests will later do with snakes.

The last day starts with a footrace to honor the snakes. The snakes are washed and deposited in the kisi. The Snake priests dance around the kisi. Each is accompanied by two other priests: one holding a snake whip and one whose function will be to catch the snake when it is dropped. Then each priest takes a snake and carries it first in his hands and then in his mouth. The whipper dances behind him with his left arm around the dancer’s neck and calms the snake by stroking it with a feathered wand. After four dances around the plaza, the priests throw the snakes to the catchers. A priest draws a circle on the ground, the catchers throw the snakes in the circle, the Snake priests grab handfuls of them and run with them to turn them loose in the desert.

Snake

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Description: Watercolor (1987) | Image Size: 13”h x 22”w; Framed Size: 23 3/8”h x 31 7/8”wpainting

One of several depictions by David Halbach of this important Hopi ceremony, “Snake” combines the artist’s ability to authentically capture the customs of the Hopi and to expertly render the surrounding landscape and village. Halbach shows that he is both a student of these important customs and a keen observer of the natural and man-made environment. He gives equal weight to the ceremony participants and the unique elements and formations of their surroundings presenting a complete picture of the people and the landscape.

When Up is Down

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Description: Watercolor (1986) | Image Size: 12”h x 19”w; Framed Size: 21”h x 28”wpainting

Halbach’s knack as a storyteller and visual historian of the West is fully evident in this picture of a frontier photographer setting up a portrait of a Plains Tribal Chief and his family. While the photographer tends to his subjects, curious onlookers surround the camera equipment. Note that the chief’s image appears upside down as it would during that time. Halbach has cleverly titled the #watercolor “When Up is Down”, a subtle nod to period authenticity.

As always, Halbach is careful to add these authentic details of the era, the location and the culture depicted. The carefully chosen colors range from vibrant to neutral and have been used advantageously to artfully depict the glancing sunlight and full shadows. Each element is handled well with the result being a fully realized vignette from the historical West.

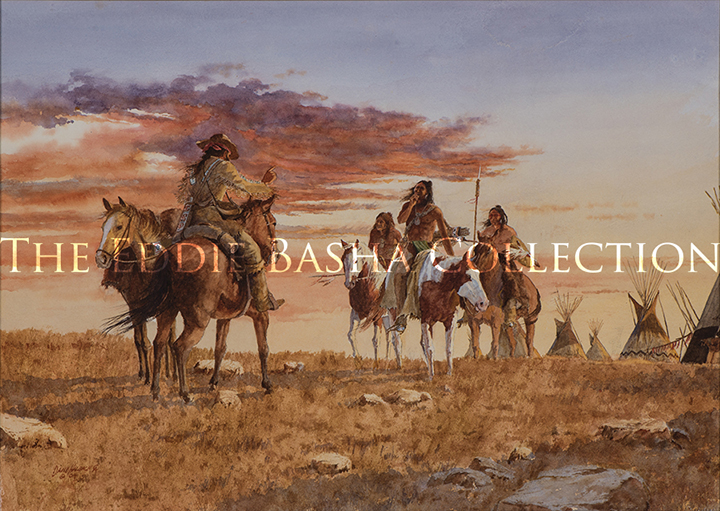

Prairie Council

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Description: Watercolor (1997) | Image Size: 16”h x 24”w; Framed Size: 27”h x 35”wpainting

When Talk Fails

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Description: Watercolor (2004) | Image Size: 21.5”h x 29.5”w; Framed Size: 36.5h”h x 45.5”wpainting

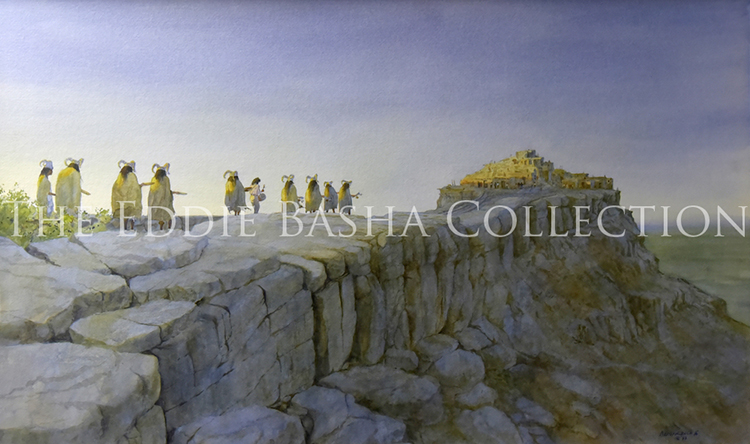

Wuwuchim Society

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Description: Watercolor (1999) | Image Size: 22.5”h x 39.5”w; Framed Size: 37”h x 53”wpainting

The Wuwuchim ceremony is part of the traditions of the Hopi Indians of North America. The history of this and other Native American cultures dates back thousands of years into prehistoric times. According to many scholars, the people who became the Native Americans migrated from Asia across a land bridge that may have once connected the territories presently occupied by Alaska and Russia. The migrations, believed to have begun between 60,000 and 30,000 B . C . E ., continued until approximately 4,000 B . C . E . This speculation, however, conflicts with traditional stories asserting that the indigenous Americans have always lived in North America or that tribes moved up from the south.

The historical development of religious belief systems among Native Americans is not well known. Most of the information available was gathered by Europeans who arrived on the continent beginning in the sixteenth century C . E . The data they recorded was fragmentary and oftentimes of questionable accuracy because the Europeans did not understand the native cultures they were trying to describe and the Native Americans were reluctant to divulge details about themselves.

The Hopi Indian ceremony known as Wuwuchim takes place in November and marks the beginning of a new ceremonial year in the Hopi calendar. The name is believed to have derived from the Hopi word wuwutani, which means "to grow up," and the initiation of young men into the sacred societies that oversee this and other Hopi ceremonies is an important part of the celebration. The tribal elders close off all roads leading to the pueblo, all fires are extinguished, and the women and children stay indoors. The initiation rituals take place in the underground chamber known as the Kiva , where the adolescent boys are gathered and where they participate in secret ceremonies that introduce them to Hopi religious customs and beliefs. Although visitors and even other tribe members are not allowed to witness these rites, they are overseen by a tribal chief who impersonates Masau ' U , the Hopi god of death and the ruler of the underworld. After they have undergone their initiation, the young men are treated as adults and allowed to dance as kachinas in other Hopi ceremonies throughout the year. Wuwuchim is therefore essential to the continuing cycle of Hopi ceremonial life.

The kindling of the new fire is the first ritual to take place during Wuwuchim. Other tribes observe this ritual around the time of the Winter Solstice , but the fact that it is part of Wuwuchim underscores the latter's importance as the start of the Hopi New Year. As the ceremony draws to a close, there are prayers, songs, and dances designed to ensure the safety and success of the Hopi people in the coming year.

Watercolor (2004) | Image Size: 21 ½”h x 29 ½”w; Framed Size: 36 ¼”h x 44 7/8”w

Watercolor (2004) | Image Size: 21 ½”h x 29 ½”w; Framed Size: 36 ¼”h x 44 7/8”w Set beneath the rapidly diminishing colors of a fading sunset, this scene from the frontier presents a lone trapper and group of Indians attempting to communicate. Failing to understand one another through spoken words, the group uses expressions and hand signals to get their points across. The figures are framed on one side by a group of teepees and on the other by the sunset lit clouds. The action of the painting is fixed between those two anchors prompting the viewer to speculate on just what messages are being communicated. While the focus of the painting is clearly the group of figures, the background of a rocky landscape and the multicolored clouds add another layer of drama to the scene.

Cowboy Artist of America Member, David Halbach, was masterful in his selection of portraying unique perspectives of the old west an equally masterful working in his favorite medium, watercolor. “When Talk Fails” made its debut at the 39th Annual Cowboy Artists of America Exhibition & Sale, Phoenix Art Museum, October 2004.

When Talk Fails

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Set beneath the rapidly diminishing colors of a fading sunset, this scene from the frontier presents a lone trapper and group of Indians attempting to communicate. Failing to understand one another through spoken words, the group uses expressions and hand signals to get their points across. The figures are framed on one side by a group of teepees and on the other by the sunset lit clouds. The action of the painting is fixed between those two anchors prompting the viewer to speculate on just what messages are being communicated. While the focus of the painting is clearly the group of figures, the background of a rocky landscape and the multicolored clouds add another layer of drama to the scene.

Cowboy Artist of America Member, David Halbach, was masterful in his selection of portraying unique perspectives of the old west an equally masterful working in his favorite medium, watercolor. “When Talk Fails” made its debut at the 39th Annual Cowboy Artists of America Exhibition & Sale, Phoenix Art Museum, October 2004.

Watercolor (1987) | Image Size: 16”h x 14”w; Framed Size: 26 ½”h x 23 7/16w

Watercolor (1987) | Image Size: 16”h x 14”w; Framed Size: 26 ½”h x 23 7/16wThis David Halbach watercolor gives the viewer a dramatic insight into the heart of one of the Hopi People’s most important ceremonies, the Snake Dance. Here, several priests are seen in a kiva about to ascend by ladder into the village. Sunlight pours in from the kiva opening above them and reveals the many accouterments and preparatory elements of the ceremony. The painting's striking vertical composition accentuates the action unfolding. Of all Halbach’s many depictions of the Snake Dance, this is one of his most theatrical.

Snake Priests (Hopi)

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

This David Halbach watercolor gives the viewer a dramatic insight into the heart of one of the Hopi People’s most important ceremonies, the Snake Dance. Here, several priests are seen in a kiva about to ascend by ladder into the village. Sunlight pours in from the kiva opening above them and reveals the many accouterments and preparatory elements of the ceremony. The painting's striking vertical composition accentuates the action unfolding. Of all Halbach’s many depictions of the Snake Dance, this is one of his most theatrical.

Watercolor (1995) | Image Size: 14”h x 22”w; Framed Size: 23”h x 31 3/4”w

Watercolor (1995) | Image Size: 14”h x 22”w; Framed Size: 23”h x 31 3/4”w David Halbach is a versatile watercolorist who is adept at painting many different subjects from the American West, both historical subjects and contemporary scenes. Here, he focuses his attention on a scene from the fur trade era—a trapper and his Indian guide are setting out by canoe on a fog shrouded waterway. In the far distance, barely visible in the fog is the faint outline of another canoe. The two figures in the canoe are depicted in detail with the trapper clad in a white shirt that focuses the viewer’s attention on the center of the painting and guides his eye toward the front of the canoe and beyond into the haze. Halbach places his viewers into the scene and at the beginning of a journey whose outcome has not been determined. The scene is just the beginning of a story from this particular era. The overall effect is an atmosphere of anticipation.

“Hudson Bay Trappers” was depicted in the book entitled “Cowboy Artists of America” authored by Michael Duty and published by the Greenwich Workshop Inc. in 2002. It was also featured at the Phippen Museum (Prescott, AZ) exhibition, “Cool, Cool Water” in 2018.

Hudson Bay Trappers

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

David Halbach is a versatile watercolorist who is adept at painting many different subjects from the American West, both historical subjects and contemporary scenes. Here, he focuses his attention on a scene from the fur trade era—a trapper and his Indian guide are setting out by canoe on a fog shrouded waterway. In the far distance, barely visible in the fog is the faint outline of another canoe. The two figures in the canoe are depicted in detail with the trapper clad in a white shirt that focuses the viewer’s attention on the center of the painting and guides his eye toward the front of the canoe and beyond into the haze. Halbach places his viewers into the scene and at the beginning of a journey whose outcome has not been determined. The scene is just the beginning of a story from this particular era. The overall effect is an atmosphere of anticipation.

“Hudson Bay Trappers” was depicted in the book entitled “Cowboy Artists of America” authored by Michael Duty and published by the Greenwich Workshop Inc. in 2002. It was also featured at the Phippen Museum (Prescott, AZ) exhibition, “Cool, Cool Water” in 2018.

Watercolor (1986) | Image Size: 10”h x 16”w ; Framed Size: 20 ½”h x 25 ¼”w

Watercolor (1986) | Image Size: 10”h x 16”w ; Framed Size: 20 ½”h x 25 ¼”w Returning to one of his favorite subjects,

Cowboy Artists of America Member David Halbach depicts in “Antelope Priests”

the beginning of an important Hopi ceremony, the Snake Dance. He has presented the ceremony in many paintings with each painting showing a different facet of the cultural custom. Here the priests emerge through an adobe portico as they proceed to the beginning

of the ceremony. Halbach uses one of his most effective motifs to spotlight the movement of the priests, the transition from darkness to light. Here he uses sunlight to focus attention on the priests while much of their surroundings are shown in deep shadow.

Antelope Priests

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Returning to one of his favorite subjects,

Cowboy Artists of America Member David Halbach depicts in “Antelope Priests”

the beginning of an important Hopi ceremony, the Snake Dance. He has presented the ceremony in many paintings with each painting showing a different facet of the cultural custom. Here the priests emerge through an adobe portico as they proceed to the beginning

of the ceremony. Halbach uses one of his most effective motifs to spotlight the movement of the priests, the transition from darkness to light. Here he uses sunlight to focus attention on the priests while much of their surroundings are shown in deep shadow.

Watercolor (1998) | Image Size: 20”h x 30”w; Framed Size: 31”h x 41 ½”w

Watercolor (1998) | Image Size: 20”h x 30”w; Framed Size: 31”h x 41 ½”wOne of the most important Hopi ceremonies is the Powamu Ceremony, or Bean Ceremony, which typically occurs during February. The Powamu is much anticipated as it is designed to promote fertility and germination for the upcoming growing season. Hopi males already initiated are expected to begin the germination process by planting seeds in the kivas and these seedlings along with ceremonial bundles are interpreted as offerings as well as omens for a successful growing season during the ceremony. The Muyˊingwa or two-horned katsina, the deity of germination, presides over the ceremony. The Powamu Ceremony is not always singular in nature, but rather can be entwined with other ceremonials such as the initiation of tribal youth into the Powamu and Katsina Societies that typical occur every three to four years.

Cowboy Artist of America member, David Halbach, had great respect for and a keen interest in the religious ceremonies of the indigenous people of the Southwest. His depictions of Hopi ceremonials, such as this one, offer an insight into customs that few outsiders are privileged to see. Here ceremonial participants are shown in authentic, detailed katsina garb in front of a Hopi pueblo structure. Villagers are shown viewing the ceremony from various vantage points atop the dwellings and on the ground. Daybreak provides the primary light source and bathes the dancers in a cool white light that offers a contrast to the dark blue of the morning sky and the beige of the adobe. The main watercolor focus is on the ceremonial participants in the middle foreground.

Powamu Ceremony

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

One of the most important Hopi ceremonies is the Powamu Ceremony, or Bean Ceremony, which typically occurs during February. The Powamu is much anticipated as it is designed to promote fertility and germination for the upcoming growing season. Hopi males already initiated are expected to begin the germination process by planting seeds in the kivas and these seedlings along with ceremonial bundles are interpreted as offerings as well as omens for a successful growing season during the ceremony. The Muyˊingwa or two-horned katsina, the deity of germination, presides over the ceremony. The Powamu Ceremony is not always singular in nature, but rather can be entwined with other ceremonials such as the initiation of tribal youth into the Powamu and Katsina Societies that typical occur every three to four years.

Cowboy Artist of America member, David Halbach, had great respect for and a keen interest in the religious ceremonies of the indigenous people of the Southwest. His depictions of Hopi ceremonials, such as this one, offer an insight into customs that few outsiders are privileged to see. Here ceremonial participants are shown in authentic, detailed katsina garb in front of a Hopi pueblo structure. Villagers are shown viewing the ceremony from various vantage points atop the dwellings and on the ground. Daybreak provides the primary light source and bathes the dancers in a cool white light that offers a contrast to the dark blue of the morning sky and the beige of the adobe. The main watercolor focus is on the ceremonial participants in the middle foreground.

Watercolor (1992) | Image Size: 16”h x 24 ½”w; Framed Size: 26 3/8”h X 35”w

Watercolor (1992) | Image Size: 16”h x 24 ½”w; Framed Size: 26 3/8”h X 35”wThe pink parasol provides a surprising focal point drawing the viewer’s eye into the journey and toward the group of Navajo travelers making its way on a lightly snow-covered landscape toward a hogan situated at the base of a steep canyon wall. Above the parasol the misty white cloud will soon burn away in the developing sunlight. David Halbach leaves the exact details of his story to the imagination of the viewer. Are the travelers visitors or are they returning home? Either way, a warming fire awaits their arrival. In this watercolor Halbach reveals a keen eye for the beauty and nuances of the atmospheric landscape and the narrative flair of an accomplished storyteller.

“Pink Parasol” won the water soluble silver medal at the 27th Annual Cowboy Artists of America Exhibition & Sale held at the Phoenix Art Museum in 1992. It was subsequently loaned to Western Spirit Scottsdale’s Museum of the West for its “A Salute to Cowboy Artists of America and a Patron, the late Eddie Basha: 50 Years of Amazing Contributions to the American West” Exhibition (November 2015-May 2016).

Pink Parasol

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

The pink parasol provides a surprising focal point drawing the viewer’s eye into the journey and toward the group of Navajo travelers making its way on a lightly snow-covered landscape toward a hogan situated at the base of a steep canyon wall. Above the parasol the misty white cloud will soon burn away in the developing sunlight. David Halbach leaves the exact details of his story to the imagination of the viewer. Are the travelers visitors or are they returning home? Either way, a warming fire awaits their arrival. In this watercolor Halbach reveals a keen eye for the beauty and nuances of the atmospheric landscape and the narrative flair of an accomplished storyteller.

“Pink Parasol” won the water soluble silver medal at the 27th Annual Cowboy Artists of America Exhibition & Sale held at the Phoenix Art Museum in 1992. It was subsequently loaned to Western Spirit Scottsdale’s Museum of the West for its “A Salute to Cowboy Artists of America and a Patron, the late Eddie Basha: 50 Years of Amazing Contributions to the American West” Exhibition (November 2015-May 2016).

Watercolor | Image Size: 9”h x 17”w; Framed Size: 15 ½”h x 24”w

Watercolor | Image Size: 9”h x 17”w; Framed Size: 15 ½”h x 24”wIn this scene of modern day ranch life, David Halbach covers most of his canvas with a snow-covered landscape surrounding the weathered barn and the washed out sky of a winter’s day. Such a stark backdrop allows him to rivet our attention on the cowboy roping the fleeing calf. The cowboy and calf run toward the viewer and are caught mid-action. Behind them, the gray boards of the barn depict a structure that has seen many winters. By depicting the sky and landscape with a minimum of detail, Halbach is able to convey a sense of the isolation of the scene and to highlight the narrative that is unfolding.

Jail Break

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

In this scene of modern day ranch life, David Halbach covers most of his canvas with a snow-covered landscape surrounding the weathered barn and the washed out sky of a winter’s day. Such a stark backdrop allows him to rivet our attention on the cowboy roping the fleeing calf. The cowboy and calf run toward the viewer and are caught mid-action. Behind them, the gray boards of the barn depict a structure that has seen many winters. By depicting the sky and landscape with a minimum of detail, Halbach is able to convey a sense of the isolation of the scene and to highlight the narrative that is unfolding.

Watercolor (1997) | Image Size: 21”h x 11”w; Framed Size: 1 9/16”h x 21 ½”w

Watercolor (1997) | Image Size: 21”h x 11”w; Framed Size: 1 9/16”h x 21 ½”wIn this watercolor, David Halbach effectively uses a vertical format to depict the steep canyon walls where a narrow set of stairs has been carved from the stone surroundings. American Indian figures are shown making their way up the stairs in the foreground, the middle distance, and the back ground. Several more figures are seen at the distant top of the canyon walls. By placing his figures in groups, Halbach gives the viewer the illusion of continuing movement as the participants of the ceremony make their way up the passageway. His subjects move from deep shadows at the canyon floor to bright sunlight at the very top. The contrast between the darkness and cool colors of the shadows and the bright sunlight and warmer tones of the upper canyon walls is quite dramatic.

“The Antelope Ceremony Begins” made its debut at the 1997 Cowboy Artists of America exhibition held at the Phoenix Art Museum.

The Antelope Ceremony Begins

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

In this watercolor, David Halbach effectively uses a vertical format to depict the steep canyon walls where a narrow set of stairs has been carved from the stone surroundings. American Indian figures are shown making their way up the stairs in the foreground, the middle distance, and the back ground. Several more figures are seen at the distant top of the canyon walls. By placing his figures in groups, Halbach gives the viewer the illusion of continuing movement as the participants of the ceremony make their way up the passageway. His subjects move from deep shadows at the canyon floor to bright sunlight at the very top. The contrast between the darkness and cool colors of the shadows and the bright sunlight and warmer tones of the upper canyon walls is quite dramatic.

“The Antelope Ceremony Begins” made its debut at the 1997 Cowboy Artists of America exhibition held at the Phoenix Art Museum.

Watercolor (1986) | Image Size: 12”h x 21”w; Framed Size: 22 ¾”h x 31 ¾”w

Watercolor (1986) | Image Size: 12”h x 21”w; Framed Size: 22 ¾”h x 31 ¾”wDavid Halbach uses a circular motif to tell this story from the fur trade era of the American West. A lantern on a pole placed in the center of the painting radiates a bright circle of light where two trappers are sorting pelts. Beyond them in the darkness, Halbach, still maintaining a circular composition, arranges other trappers and their horses on the top left arc of the circle and a trade boat being loaded on the top right arc. The contrast between the bright light of the lantern and the darkness of the surrounding landscape is quite effective in telling the story of “Pelts for Provisions” that adds a dramatic touch to the scene.

Pelts for Provisions

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

David Halbach uses a circular motif to tell this story from the fur trade era of the American West. A lantern on a pole placed in the center of the painting radiates a bright circle of light where two trappers are sorting pelts. Beyond them in the darkness, Halbach, still maintaining a circular composition, arranges other trappers and their horses on the top left arc of the circle and a trade boat being loaded on the top right arc. The contrast between the bright light of the lantern and the darkness of the surrounding landscape is quite effective in telling the story of “Pelts for Provisions” that adds a dramatic touch to the scene.

Watercolor | Image Size: 16”h x 28”w; Framed Size: 26 ½”h x 38”w

Watercolor | Image Size: 16”h x 28”w; Framed Size: 26 ½”h x 38”wAs the subjects head through the shaded bend of the canyon wall, one of the riders alerts his companions by pointing towards the “omen” that presents just beyond on the other side of the shoreline ... a coup stick delineating “territorial” rights of another tribe. The sunlight in that area seems to be more absorbed than reflected by the stream projecting an aura of drama to the scene unfolding.

One of the more difficult tasks faced by a painter, particularly a watercolorist, is to effectively juxtapose very different textures such as the hard and craggy surface of a canyon wall and the reflective nature of standing water. In “Territorial Omen,” Halbach is able to achieve that juxtaposition in a highly authentic way. His water has a realistic shimmer and his canyon wall has a depth that makes one want to touch it. He also masterfully contrasts dark and light spaces to assist in casting the potential for an element of danger.

First appearing at the 31st Annual Cowboy Artists of America Exhibition & Sale in 1996 at the Phoenix Art Museum, Halbach’s “Territorial Omen” was more recently loaned to the Phippen Museum in Prescott, Arizona, for the “Cool, Cool Water” exhibition in 2018. It remains a permanent part of the EBC.

Territorial Omen

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

As the subjects head through the shaded bend of the canyon wall, one of the riders alerts his companions by pointing towards the “omen” that presents just beyond on the other side of the shoreline ... a coup stick delineating “territorial” rights of another tribe. The sunlight in that area seems to be more absorbed than reflected by the stream projecting an aura of drama to the scene unfolding.

One of the more difficult tasks faced by a painter, particularly a watercolorist, is to effectively juxtapose very different textures such as the hard and craggy surface of a canyon wall and the reflective nature of standing water. In “Territorial Omen,” Halbach is able to achieve that juxtaposition in a highly authentic way. His water has a realistic shimmer and his canyon wall has a depth that makes one want to touch it. He also masterfully contrasts dark and light spaces to assist in casting the potential for an element of danger.

First appearing at the 31st Annual Cowboy Artists of America Exhibition & Sale in 1996 at the Phoenix Art Museum, Halbach’s “Territorial Omen” was more recently loaned to the Phippen Museum in Prescott, Arizona, for the “Cool, Cool Water” exhibition in 2018. It remains a permanent part of the EBC.

Watercolor (1994) | Image Size: 15 ½”h x 24 ¾”w; Framed Size: 25 3/8”h x 33 3/8”w

Watercolor (1994) | Image Size: 15 ½”h x 24 ¾”w; Framed Size: 25 3/8”h x 33 3/8”wThe Flute Ceremony traditionally held in August and on opposite years of the Snake Dance is a nine-day celebration encouraging rain and a successful corn crop and for the continuity of life after death. During the days leading up to the ceremony, an altar is constructed with carvings and paintings to represent the clouds that will bring rain to the villages.

The Flute Ceremony begins with a procession through the village. The clan chief leads a group that includes the flute boy, flute girls, men carrying cornstalks and warriors with bullroarers. Prayers for rain are said and a priest scatters corn meal on the ground before the flute altar. Water is poured into a bowl from all directions to symbolize the rain clouds and a bullroarer is used to represent the sound of thunder.

The unwrapping of the tiponi occurs on the sixth day of celebration. The tiponi is made of wood, shaped like a cup and decorated with rain cloud and corn symbols. Inside the cup rests a single ear of corn or corn grains. This corn represents the seed that was carried by the early tribes throughout their migrations. Wrapped in cotton string and feathers, the tiponi is unwrapped by a flute priest so the corn within can be planted. A new ear of corn is then placed within it and re-wrapped until the following year.

Flute Ceremony

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

The Flute Ceremony traditionally held in August and on opposite years of the Snake Dance is a nine-day celebration encouraging rain and a successful corn crop and for the continuity of life after death. During the days leading up to the ceremony, an altar is constructed with carvings and paintings to represent the clouds that will bring rain to the villages.

The Flute Ceremony begins with a procession through the village. The clan chief leads a group that includes the flute boy, flute girls, men carrying cornstalks and warriors with bullroarers. Prayers for rain are said and a priest scatters corn meal on the ground before the flute altar. Water is poured into a bowl from all directions to symbolize the rain clouds and a bullroarer is used to represent the sound of thunder.

The unwrapping of the tiponi occurs on the sixth day of celebration. The tiponi is made of wood, shaped like a cup and decorated with rain cloud and corn symbols. Inside the cup rests a single ear of corn or corn grains. This corn represents the seed that was carried by the early tribes throughout their migrations. Wrapped in cotton string and feathers, the tiponi is unwrapped by a flute priest so the corn within can be planted. A new ear of corn is then placed within it and re-wrapped until the following year.

Watercolor (1993) | Image Size: 15”h x 24 3/4”w; Frame Size: 27 1/6”h x 36 ¾”w

Watercolor (1993) | Image Size: 15”h x 24 3/4”w; Frame Size: 27 1/6”h x 36 ¾”wDavid Halbach has a well-deserved reputation as a visual historian of the western frontier, an excellent storyteller, and a devoted student of American Indian customs and culture. With such a wealth of talents, his prowess as a landscape painter is sometimes overlooked. “Canyon de Chelly Gold” is primarily a landscape painting. It does include figures, a rider trailing three horses toward the mouth of a canyon, but the subject of the painting is the land with its sheer reddish canyon walls that are somewhat shrouded by white mists. The viewer’s eye is led into the heart of the picture by the figures which proceed from the right foreground between the two canyon walls. The green leaves of two groves of trees add a contrasting note of color to the rock faces of the canyon, and nestled beneath one of the groves is a traditional Navajo hogan. The path between the two prominent canyon walls leads into the distance toward another wall which gives the painting a sense of depth and grandeur.

The National Park Service website says the following about Canyon de Chelly National Monument: “It is a vast park in northeastern Arizona on Navajo tribal lands. Its prominent features include Spider Rock spire, about 800-feet tall, and towering sandstone cliffs surrounding a verdant canyon. Inhabited by several Native American peoples for millennia, the area is dotted with prehistoric rock art. The White House Ruins and Mummy Cave are remains of ancient Pueblo villages.”

Canyon de Chelly Gold

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

David Halbach has a well-deserved reputation as a visual historian of the western frontier, an excellent storyteller, and a devoted student of American Indian customs and culture. With such a wealth of talents, his prowess as a landscape painter is sometimes overlooked. “Canyon de Chelly Gold” is primarily a landscape painting. It does include figures, a rider trailing three horses toward the mouth of a canyon, but the subject of the painting is the land with its sheer reddish canyon walls that are somewhat shrouded by white mists. The viewer’s eye is led into the heart of the picture by the figures which proceed from the right foreground between the two canyon walls. The green leaves of two groves of trees add a contrasting note of color to the rock faces of the canyon, and nestled beneath one of the groves is a traditional Navajo hogan. The path between the two prominent canyon walls leads into the distance toward another wall which gives the painting a sense of depth and grandeur.

The National Park Service website says the following about Canyon de Chelly National Monument: “It is a vast park in northeastern Arizona on Navajo tribal lands. Its prominent features include Spider Rock spire, about 800-feet tall, and towering sandstone cliffs surrounding a verdant canyon. Inhabited by several Native American peoples for millennia, the area is dotted with prehistoric rock art. The White House Ruins and Mummy Cave are remains of ancient Pueblo villages.”

Watercolor on Paper (1998) | Image Size: 22”h x 18”w; Framed Size: 31 ½”h x 27”w

Watercolor on Paper (1998) | Image Size: 22”h x 18”w; Framed Size: 31 ½”h x 27”w“Warnings and Portents” is an excellent example of David Halbach’s skill as an artist and storyteller. A fur trapper is crouching near a stream to fill his canteen. Halbach portrays him just at the moment that he looks up, perhaps because of an echoing canyon noise, to see a shadow cast of an approaching warrior on the rock face. We are caught in a moment filled with alarm and anticipation—just as the trapper is.

Halbach’s use of light and shadow to set the stage for the unfolding drama is a key element of the painting. He has neatly bisected the painting; the top half in bright sunlight shows the steep and rough canyon walls with the shadow of the approaching warrior. The deeply shadowed bottom half almost obscures the figure of the trapper. As a result, the viewer must concentrate to take in all the aspects of the scene from the exquisite landscape to the details of the trapper’s clothing and his accoutrements, a rifle in one hand and a canteen in the other, and the trapper poised to take whatever action will be necessary. And it is those rich features that Halbach has left not only the outcome of the story to the imagination of the viewer, but for the viewer wanting more.

This piece won the silver medal in the water soluble category at the 33rd Annual Cowboy Artists of America Show & Sale in 1998 at the Phoenix Art Museum.

Warnings and Portents

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

“Warnings and Portents” is an excellent example of David Halbach’s skill as an artist and storyteller. A fur trapper is crouching near a stream to fill his canteen. Halbach portrays him just at the moment that he looks up, perhaps because of an echoing canyon noise, to see a shadow cast of an approaching warrior on the rock face. We are caught in a moment filled with alarm and anticipation—just as the trapper is.

Halbach’s use of light and shadow to set the stage for the unfolding drama is a key element of the painting. He has neatly bisected the painting; the top half in bright sunlight shows the steep and rough canyon walls with the shadow of the approaching warrior. The deeply shadowed bottom half almost obscures the figure of the trapper. As a result, the viewer must concentrate to take in all the aspects of the scene from the exquisite landscape to the details of the trapper’s clothing and his accoutrements, a rifle in one hand and a canteen in the other, and the trapper poised to take whatever action will be necessary. And it is those rich features that Halbach has left not only the outcome of the story to the imagination of the viewer, but for the viewer wanting more.

This piece won the silver medal in the water soluble category at the 33rd Annual Cowboy Artists of America Show & Sale in 1998 at the Phoenix Art Museum.

Watercolor | Image Size: 16”h x 24”w; Framed Size: 25”h x 32 7/8”w

Watercolor | Image Size: 16”h x 24”w; Framed Size: 25”h x 32 7/8”wIn “Fire that Talks,” Halbach isolates Indians on a vast plain who are using smoke from a small fire to send a message to distant comrades. The Indians are shown in the center of the canvas in full light, but shadows indicate that daylight will soon be waning, making signals such as this one impossible. The white puff of smoke emanating from the fire in the very center of the painting captures the viewer’s attention and immerses him in the unfolding story.

“Fire that Talks” made its debut at the Cowboy Artists of America Silver Anniversary Exhibit at The Museum of Western Art in Kerrville, Texas (April-September 1990) and later that same year at the 25th Silver Anniversary Exhibition & Sale held at the Phoenix Art Museum (October-November 1990).

Fire that Talks

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

In “Fire that Talks,” Halbach isolates Indians on a vast plain who are using smoke from a small fire to send a message to distant comrades. The Indians are shown in the center of the canvas in full light, but shadows indicate that daylight will soon be waning, making signals such as this one impossible. The white puff of smoke emanating from the fire in the very center of the painting captures the viewer’s attention and immerses him in the unfolding story.

“Fire that Talks” made its debut at the Cowboy Artists of America Silver Anniversary Exhibit at The Museum of Western Art in Kerrville, Texas (April-September 1990) and later that same year at the 25th Silver Anniversary Exhibition & Sale held at the Phoenix Art Museum (October-November 1990).

Watercolor (1997) | Image Size: 13”h x 23 ½”w; Framed Size: 22”h x 32”w

Watercolor (1997) | Image Size: 13”h x 23 ½”w; Framed Size: 22”h x 32”w“Just Makin’ It” took home the Silver Medal in water solubles at the 32nd Annual CAA Exhibition & Sale at the Phoenix Art Museum in 1997. Dave Halbach masterfully captured the reflective quality of water and easily combined other textures such as the weathered wood of the barn and wagon, the horses’ coats, and that of the hay. The painting though executed in muted colors, has quite distinct scene details. Halbach effectively presented a narrative that is representative of just one of the many arduous and necessary tasks of ranching.

Just Makin’ It

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

“Just Makin’ It” took home the Silver Medal in water solubles at the 32nd Annual CAA Exhibition & Sale at the Phoenix Art Museum in 1997. Dave Halbach masterfully captured the reflective quality of water and easily combined other textures such as the weathered wood of the barn and wagon, the horses’ coats, and that of the hay. The painting though executed in muted colors, has quite distinct scene details. Halbach effectively presented a narrative that is representative of just one of the many arduous and necessary tasks of ranching.

Watercolor | Image Size: 12”h x 16”w; Framed Size: 18 ¾”h X 22 ¾”w

Watercolor | Image Size: 12”h x 16”w; Framed Size: 18 ¾”h X 22 ¾”wThe Hopi Snake Antelope Ceremony is the grand finale of ceremonies to pray for rain. The ceremonies, conducted by the Snake and Antelope fraternities, last 16 days. On the 11th day, preparations start for the Snake Dance. For four days, snake priests go out from their village to gather snakes. On the 15th day, a race is run, signifying rain gods brining water to the village. Then the Antelope build a kisi, a shallow pit covered with a board to represent the entrance to the underworld. At sunset on the 15th day, the Snake and Antelope dancers dance around the plaza, stamping on the kisi board and shaking rattles to simulate the sounds of thunder and rain. The Antelope priest dances with green vines around his neck and his mouth, just as the Snake priests will later do with snakes.

The last day starts with a footrace to honor the snakes. The snakes are washed and deposited in the kisi. The Snake priests dance around the kisi. Each is accompanied by two other priests: one holding a snake whip and one whose function will be to catch the snake when it is dropped. Then each priest takes a snake and carries it first in his hands and then in his mouth. The whipper dances behind him with his left arm around the dancer’s neck and calms the snake by stroking it with a feathered wand. After four dances around the plaza, the priests throw the snakes to the catchers. A priest draws a circle on the ground, the catchers throw the snakes in the circle, the Snake priests grab handfuls of them and run with them to turn them loose in the desert.

Evoking Clouds - The Snake-Antelope Ceremony - Mishongnovi

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

The Hopi Snake Antelope Ceremony is the grand finale of ceremonies to pray for rain. The ceremonies, conducted by the Snake and Antelope fraternities, last 16 days. On the 11th day, preparations start for the Snake Dance. For four days, snake priests go out from their village to gather snakes. On the 15th day, a race is run, signifying rain gods brining water to the village. Then the Antelope build a kisi, a shallow pit covered with a board to represent the entrance to the underworld. At sunset on the 15th day, the Snake and Antelope dancers dance around the plaza, stamping on the kisi board and shaking rattles to simulate the sounds of thunder and rain. The Antelope priest dances with green vines around his neck and his mouth, just as the Snake priests will later do with snakes.

The last day starts with a footrace to honor the snakes. The snakes are washed and deposited in the kisi. The Snake priests dance around the kisi. Each is accompanied by two other priests: one holding a snake whip and one whose function will be to catch the snake when it is dropped. Then each priest takes a snake and carries it first in his hands and then in his mouth. The whipper dances behind him with his left arm around the dancer’s neck and calms the snake by stroking it with a feathered wand. After four dances around the plaza, the priests throw the snakes to the catchers. A priest draws a circle on the ground, the catchers throw the snakes in the circle, the Snake priests grab handfuls of them and run with them to turn them loose in the desert.

Watercolor (1987) | Image Size: 13”h x 22”w; Framed Size: 23 3/8”h x 31 7/8”w

Watercolor (1987) | Image Size: 13”h x 22”w; Framed Size: 23 3/8”h x 31 7/8”wOne of several depictions by David Halbach of this important Hopi ceremony, “Snake” combines the artist’s ability to authentically capture the customs of the Hopi and to expertly render the surrounding landscape and village. Halbach shows that he is both a student of these important customs and a keen observer of the natural and man-made environment. He gives equal weight to the ceremony participants and the unique elements and formations of their surroundings presenting a complete picture of the people and the landscape.

Snake

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

One of several depictions by David Halbach of this important Hopi ceremony, “Snake” combines the artist’s ability to authentically capture the customs of the Hopi and to expertly render the surrounding landscape and village. Halbach shows that he is both a student of these important customs and a keen observer of the natural and man-made environment. He gives equal weight to the ceremony participants and the unique elements and formations of their surroundings presenting a complete picture of the people and the landscape.

Watercolor (1986) | Image Size: 12”h x 19”w; Framed Size: 21”h x 28”w

Watercolor (1986) | Image Size: 12”h x 19”w; Framed Size: 21”h x 28”wHalbach’s knack as a storyteller and visual historian of the West is fully evident in this picture of a frontier photographer setting up a portrait of a Plains Tribal Chief and his family. While the photographer tends to his subjects, curious onlookers surround the camera equipment. Note that the chief’s image appears upside down as it would during that time. Halbach has cleverly titled the #watercolor “When Up is Down”, a subtle nod to period authenticity.

As always, Halbach is careful to add these authentic details of the era, the location and the culture depicted. The carefully chosen colors range from vibrant to neutral and have been used advantageously to artfully depict the glancing sunlight and full shadows. Each element is handled well with the result being a fully realized vignette from the historical West.

When Up is Down

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Halbach’s knack as a storyteller and visual historian of the West is fully evident in this picture of a frontier photographer setting up a portrait of a Plains Tribal Chief and his family. While the photographer tends to his subjects, curious onlookers surround the camera equipment. Note that the chief’s image appears upside down as it would during that time. Halbach has cleverly titled the #watercolor “When Up is Down”, a subtle nod to period authenticity.

As always, Halbach is careful to add these authentic details of the era, the location and the culture depicted. The carefully chosen colors range from vibrant to neutral and have been used advantageously to artfully depict the glancing sunlight and full shadows. Each element is handled well with the result being a fully realized vignette from the historical West.

Watercolor (1997) | Image Size: 16”h x 24”w; Framed Size: 27”h x 35”w

Watercolor (1997) | Image Size: 16”h x 24”w; Framed Size: 27”h x 35”wPrairie Council

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Watercolor (2004) | Image Size: 21.5”h x 29.5”w; Framed Size: 36.5h”h x 45.5”w

Watercolor (2004) | Image Size: 21.5”h x 29.5”w; Framed Size: 36.5h”h x 45.5”wWhen Talk Fails

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

Watercolor (1999) | Image Size: 22.5”h x 39.5”w; Framed Size: 37”h x 53”w

Watercolor (1999) | Image Size: 22.5”h x 39.5”w; Framed Size: 37”h x 53”wThe Wuwuchim ceremony is part of the traditions of the Hopi Indians of North America. The history of this and other Native American cultures dates back thousands of years into prehistoric times. According to many scholars, the people who became the Native Americans migrated from Asia across a land bridge that may have once connected the territories presently occupied by Alaska and Russia. The migrations, believed to have begun between 60,000 and 30,000 B . C . E ., continued until approximately 4,000 B . C . E . This speculation, however, conflicts with traditional stories asserting that the indigenous Americans have always lived in North America or that tribes moved up from the south.

The historical development of religious belief systems among Native Americans is not well known. Most of the information available was gathered by Europeans who arrived on the continent beginning in the sixteenth century C . E . The data they recorded was fragmentary and oftentimes of questionable accuracy because the Europeans did not understand the native cultures they were trying to describe and the Native Americans were reluctant to divulge details about themselves.

The Hopi Indian ceremony known as Wuwuchim takes place in November and marks the beginning of a new ceremonial year in the Hopi calendar. The name is believed to have derived from the Hopi word wuwutani, which means "to grow up," and the initiation of young men into the sacred societies that oversee this and other Hopi ceremonies is an important part of the celebration. The tribal elders close off all roads leading to the pueblo, all fires are extinguished, and the women and children stay indoors. The initiation rituals take place in the underground chamber known as the Kiva , where the adolescent boys are gathered and where they participate in secret ceremonies that introduce them to Hopi religious customs and beliefs. Although visitors and even other tribe members are not allowed to witness these rites, they are overseen by a tribal chief who impersonates Masau ' U , the Hopi god of death and the ruler of the underworld. After they have undergone their initiation, the young men are treated as adults and allowed to dance as kachinas in other Hopi ceremonies throughout the year. Wuwuchim is therefore essential to the continuing cycle of Hopi ceremonial life.

The kindling of the new fire is the first ritual to take place during Wuwuchim. Other tribes observe this ritual around the time of the Winter Solstice , but the fact that it is part of Wuwuchim underscores the latter's importance as the start of the Hopi New Year. As the ceremony draws to a close, there are prayers, songs, and dances designed to ensure the safety and success of the Hopi people in the coming year.

Wuwuchim Society

Artist: David Halbach, CA (1931-2022)

The Wuwuchim ceremony is part of the traditions of the Hopi Indians of North America. The history of this and other Native American cultures dates back thousands of years into prehistoric times. According to many scholars, the people who became the Native Americans migrated from Asia across a land bridge that may have once connected the territories presently occupied by Alaska and Russia. The migrations, believed to have begun between 60,000 and 30,000 B . C . E ., continued until approximately 4,000 B . C . E . This speculation, however, conflicts with traditional stories asserting that the indigenous Americans have always lived in North America or that tribes moved up from the south.

The historical development of religious belief systems among Native Americans is not well known. Most of the information available was gathered by Europeans who arrived on the continent beginning in the sixteenth century C . E . The data they recorded was fragmentary and oftentimes of questionable accuracy because the Europeans did not understand the native cultures they were trying to describe and the Native Americans were reluctant to divulge details about themselves.

The Hopi Indian ceremony known as Wuwuchim takes place in November and marks the beginning of a new ceremonial year in the Hopi calendar. The name is believed to have derived from the Hopi word wuwutani, which means "to grow up," and the initiation of young men into the sacred societies that oversee this and other Hopi ceremonies is an important part of the celebration. The tribal elders close off all roads leading to the pueblo, all fires are extinguished, and the women and children stay indoors. The initiation rituals take place in the underground chamber known as the Kiva , where the adolescent boys are gathered and where they participate in secret ceremonies that introduce them to Hopi religious customs and beliefs. Although visitors and even other tribe members are not allowed to witness these rites, they are overseen by a tribal chief who impersonates Masau ' U , the Hopi god of death and the ruler of the underworld. After they have undergone their initiation, the young men are treated as adults and allowed to dance as kachinas in other Hopi ceremonies throughout the year. Wuwuchim is therefore essential to the continuing cycle of Hopi ceremonial life.

The kindling of the new fire is the first ritual to take place during Wuwuchim. Other tribes observe this ritual around the time of the Winter Solstice , but the fact that it is part of Wuwuchim underscores the latter's importance as the start of the Hopi New Year. As the ceremony draws to a close, there are prayers, songs, and dances designed to ensure the safety and success of the Hopi people in the coming year.