Tom Lovell, CA

(1909-1997)

A Native American finds a Raggedy Ann doll on a lonely Western road. A settler is teaching his gingham dressed wife how to shoot a rifle. Three Indians warm their hands over the chimney of a snow buried cabin. These are just three of the dramatic stories that Tom Lovell told through his artwork. Lovell’s attention to detail is unmatched, and he was seldom able to complete more than a dozen paintings a year. His peers consider him one of the deans of Western art.

Lovell was born in New York City in 1909. He was the Valedictorian of his high school class; and at the graduation ceremony spoke on the “ill treatment of the American Indian by the U. S. Government.” He received a bachelor of fine arts from Syracuse University in 1931. For thirty-nine years, Lovell worked as a freelance illustrator for magazines such as Colliers, McCalls, National Geographic, Life, and the Saturday Evening Post. He was as famous for his Western art as for his stirring images of Civil War battles, which were considered so definitive that they were telecast as part of an acclaimed public television documentary and published in the accompanying best-selling book.

Lovell considered himself a “storyteller with a brush, a custodian of the past.” “I try to place myself back in time and imagine situations that would make interesting and appealing pictures. I am intent on producing paintings that relate to the human experience and our Western heritage.”

In 1974, Lovell was elected to the Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame and was later named a Hall of Fame Laureate. In 1975, he and his family moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, and he was elected to the Cowboy Artists of America the same year. In 1992, both the National Academy of Western Art and the National Cowboy Hall of Fame honored Lovell with a Lifetime Achievement Award and a prestigious one man retrospective show. He was the first artist to ever win the Prix de West – the National Academy of Western Art’s highest honor – twice.

Source: Cowboy Artists of America

Throat Spray M1 (Study)

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Description: Pencil Study | Image Size: 28 3/8”h x 24 3/8”w; Framed Size: 38 3/8”h x 34 3/8”wdrawing

Two men who became among the country’s most acclaimed magazine illustrators of their time and went on to equally illustrious careers as western artists, Tom Lovell and John Clymer, went through boot camp together and served their country during World War II. The idea for this drawing came from their shared boot camp experience at Parris Island where, with 80 men in a barracks, if anyone caught a cold, everyone shared it. John obligingly posed for it and Tom made it the subject of a Leatherneck cover.

Lovell gifted the original study to Eddie Basha in 1982. It was subsequently loaned to Western Spirit Scottsdale’s Museum of the West for the exhibition entitled “A Salute to Cowboy Artists of America and a Patron, the late Eddie Basha: 50 Years of Amazing Contributions to the American West” (Nov 2015 – May 2016) and an image of the original oil appeared in the book entitled “The Art of Tom Lovell: An Invitation to History” authored by Don Hedgpeth and Walt Reed and published by Greenwich Workshop in 1993

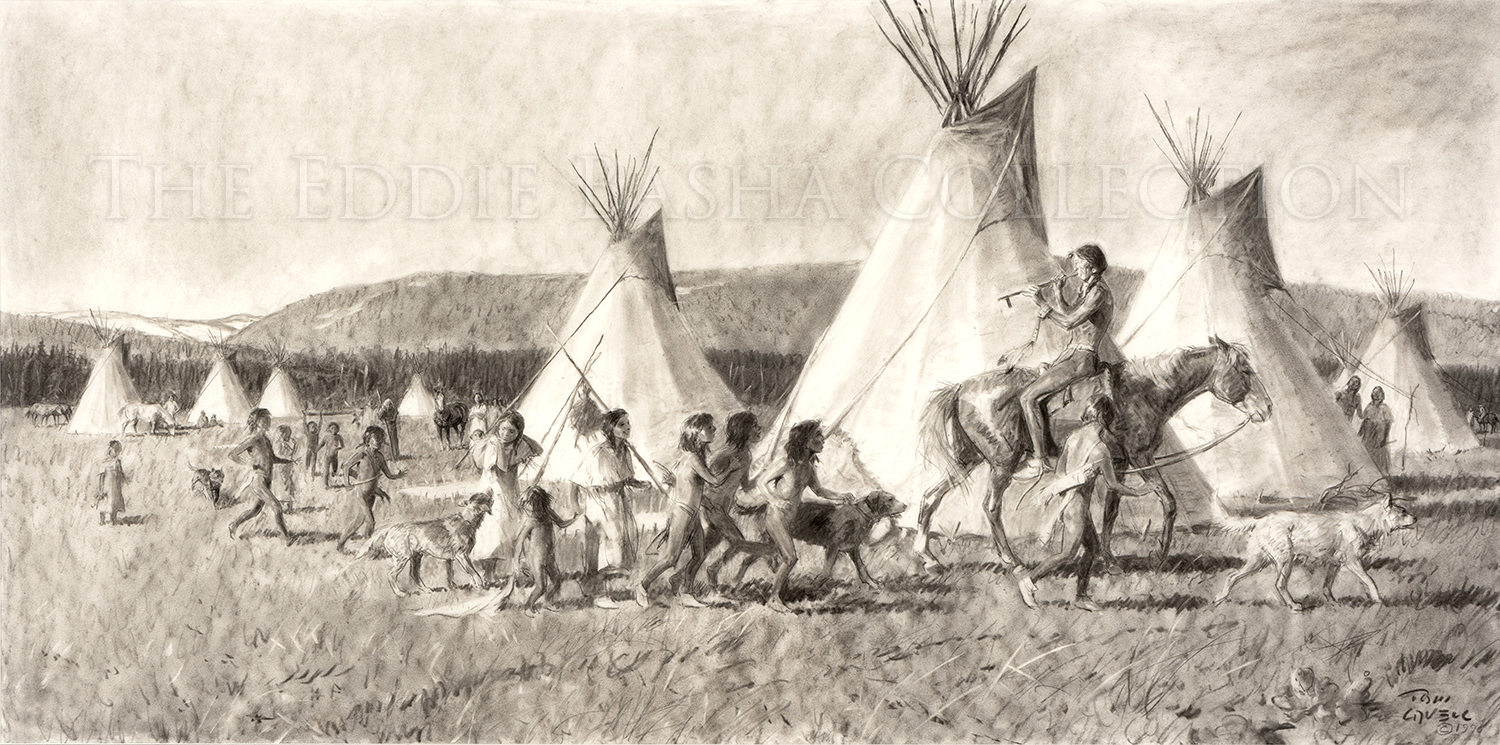

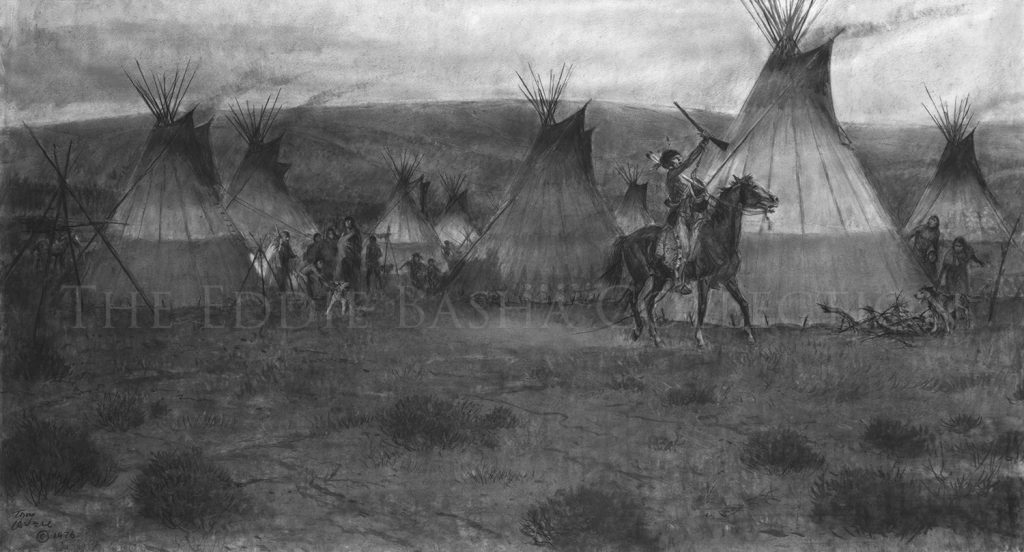

Contrary One

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Description: Charcoal/Pencil (1990) | Image Size: 20”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 27“h x 47“wdrawing

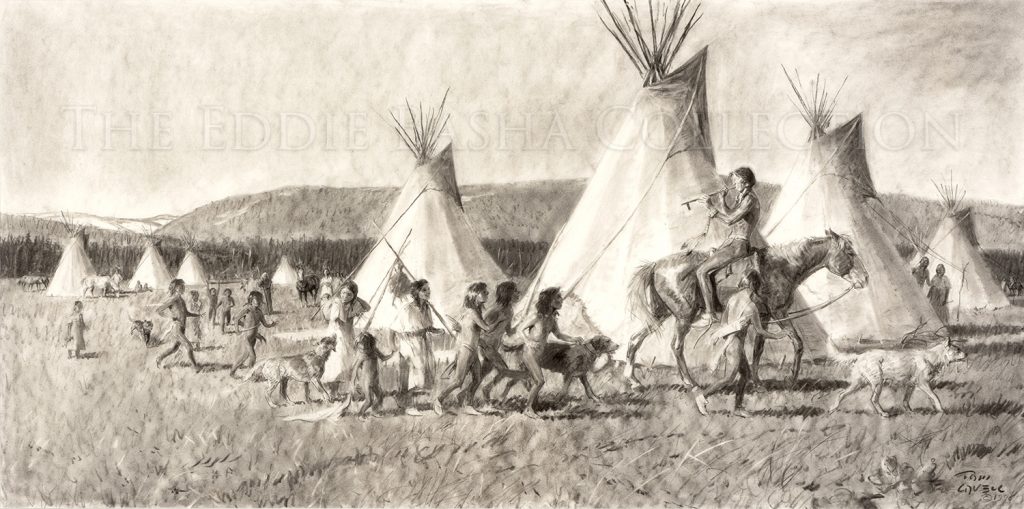

Although he often painted stories of important historic events, Tom Lovell also offered visual tales of everyday life of particular historic periods. He was a great student of American Indian history and created interesting and sometimes humorous scenes based on his research. In this study for an oil painting, he shows a young Indian leading a group of children through a small teepee village. The children seem captivated by the fact that their leader is sitting on his horse backwards. The viewer of the painting focuses on the progression of the rider as he passes the tipis riding from the left to the right edge of the canvas. Children, women, and dogs are shown trailing this unusual rider.

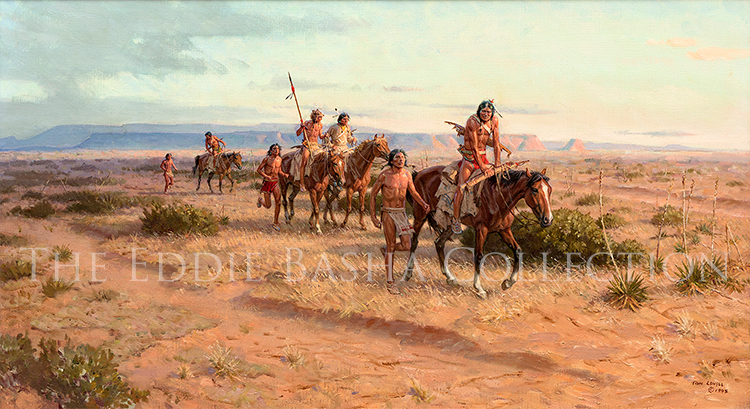

The Mud Owl’s Warning

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Description: Oil (1975) | Image Size: 23”h x 41”w; Framed Size: 32”h x 50”wpainting

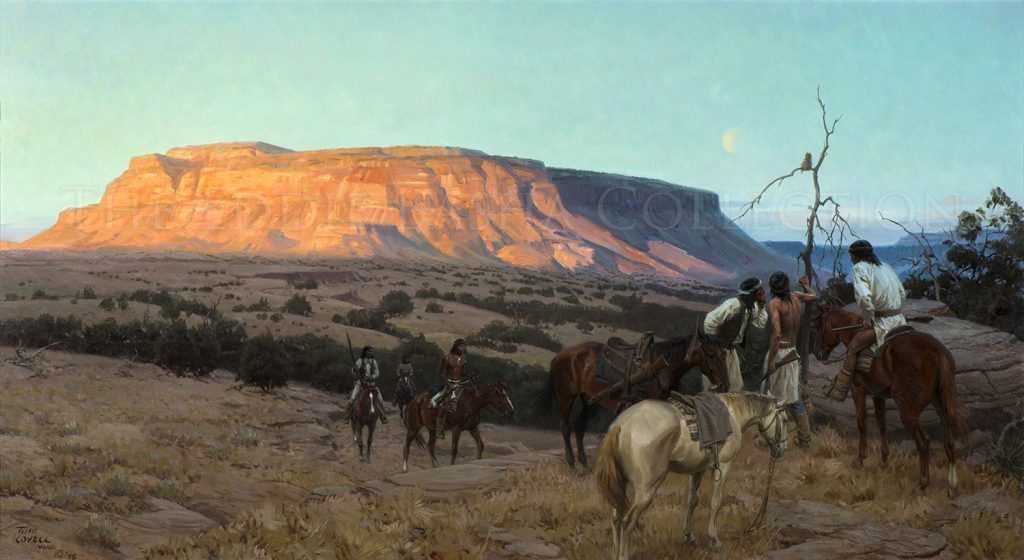

In the book The Art of Tom Lovell: An Invitation to History authored by Don Hedgpeth and Walt Reed, an image of this painting appears. The narrative provided reads “Death was a major preoccupation for the Apache. The dead were buried quickly and their possessions burned. Mourners moved their camp away from the place of death. Spirits and ghosts dwelled everywhere in the Apache's world. The owl was thought to be a messenger of death, a harbinger of disaster. When an Apache camp was struck by pestilence, mud effigies of the owl were placed along trails leading to the camp as a warning. Here a group of warriors returning after days on the trail, spot a mud owl and stop to ponder its meaning as the sun's last rays strike the distant mesa.”

Comanche Moon

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Description: Oil | Image Size: 20 ½”h x 33”w; Framed Size: 30”h x 43”wpainting

Early accounts tell us every fall that in the month of September, Comanche war parties would regularly make the long journey to raid the scattered ranches below the Rio Grande. This was the best time of year to travel because the waterholes and streams were more likely to be filled and thus parties’ tracks would be indiscernible. Comanche war parties always departed at night, and followed streams whenever practical. September became known in West Texas as the Comanche Moon.

This evocative painting of a Comanche war party traveling down a shallow stream bed under a bright moon displays Tom Lovell’s full talent as an artist and storyteller. Every element of the painting is expertly crafted from the ripples in the stream to the moonlit sandy ground beneath the horses’ feet. Lovell has masterfully depicted the moonlight that is so bright and clear that the surrounding landscape is revealed in detail. The riders progress toward the viewer in single file. Two warriors ride at the head of the column while the last rider is placed in the far background enhancing the sense of distance covered by the party. Painting water realistically is a difficult task even for the most accomplished artists and Lovell’s skill in doing so is amply evident in his stream depiction with its undulating ripples. As befitting a scene of nighttime travel, the painting evokes a sense of quiet peacefulness. In terms of the story being told of Comanche warriors en route to a raid on settlers or another Indian tribe, this quiet scene stands in sharp contrast to what will occur once these riders have passed from our viewpoint. Lovell has taken a common frontier narrative, one of conflict, drama, and action, and has chosen to present a different aspect of that account. His scene is quiet and nuanced, subsequent scenes in this tale will be quite different.

Wrong Side Up Study

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Description: Charcoal/Pencil | Image Size: 18”h x 30”w; Framed Size: 25”h x 37”wdrawing

In the book “The Art of Tom Lovell: An Invitation To History” published by Greenwich Workshop in 1993, authored by Don Hedgpeth and Walt Reed, the following was written about “Wrong Side Up”.

“What manner of men were these white people who would do such a thing to the buffalo range? The plow proved to be a deadly weapon which set in motion a sequence of destruction. Crops were planted where the buffalo had grazed; soon the great herds would be gone. Without the buffalo, the Indian was doomed. And in the end, the white farmers would abandon these places to drought and erosion, the genesis of the dust bowl days. Buffalo, Indians, homesteaders... all blown away in the rising dust clouds because the land had been turned wrong side up.

The scars are still upon the land, and deepest yet in the hearts of the descendants of Plains Indians who had understood the delicate balance of nature on the range of the buffalo.”

In this simple drawing, simple in terms of composition but complex in terms of meaning, Lovell’s prowess as a storyteller who could paint scenes from many different points of view is highlighted.

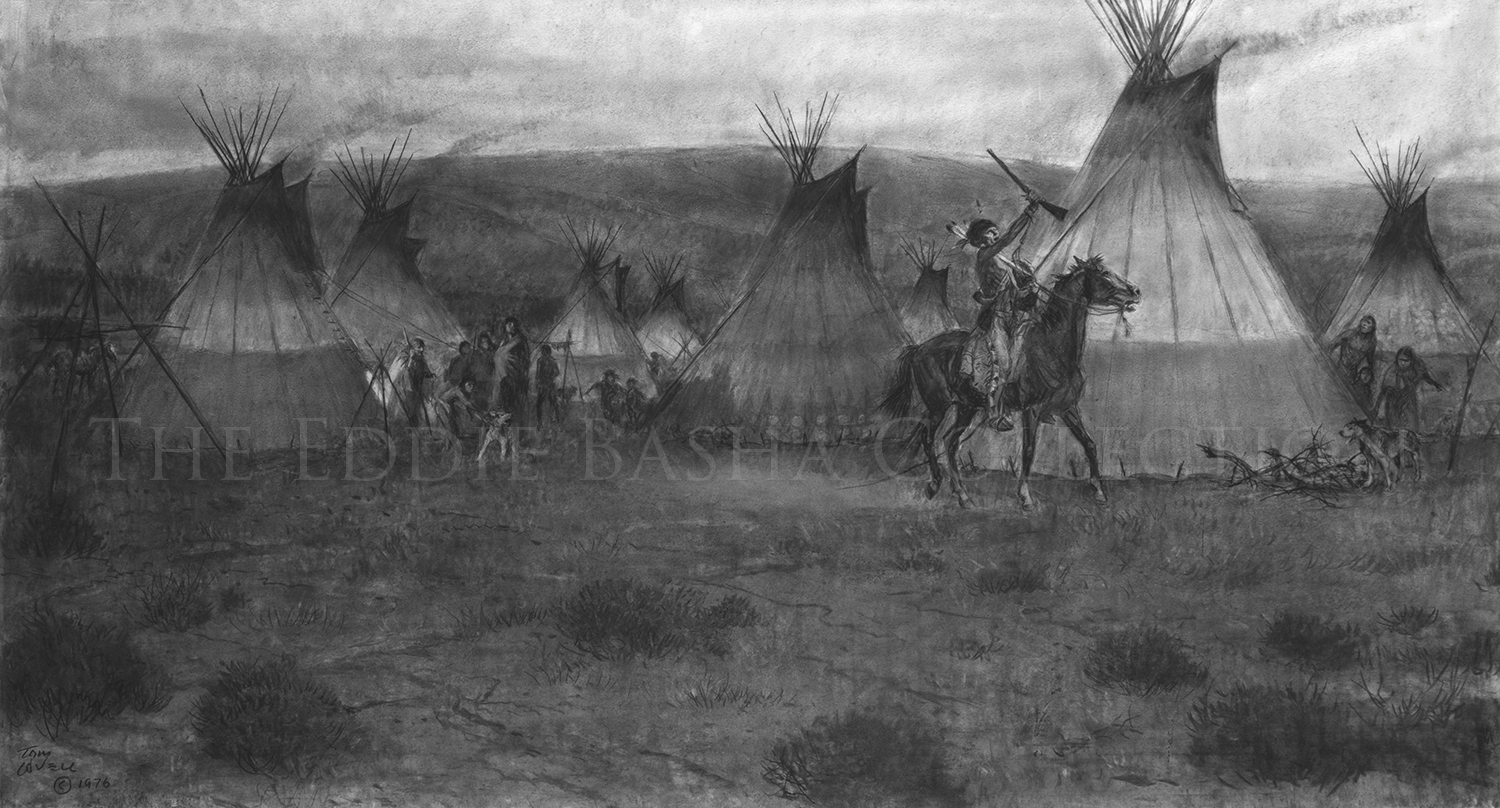

The Recruiter (Drawing)

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Description: Charcoal & Pencil (1976) | Image Size: 22”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 29”h x 47”wdrawing

The Recruiter

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Description: Oil (1974) | Image Size: 22”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 32”h x 49”wpainting

The Piegan were a northern tribe, a branch of the Blackfeet. Pioneer photographer and historian, Edward Curtis, related when speaking of their customs that “when a successful warrior wanted to lead a war party he caught his best horse, held his gun high above his head and rode around the camp singing a war song. It was a signal for all who wanted to follow him to start repairing their weapons and moccasins. On the following morning the leader saddled, rode away and assembled the men on a nearby hill."

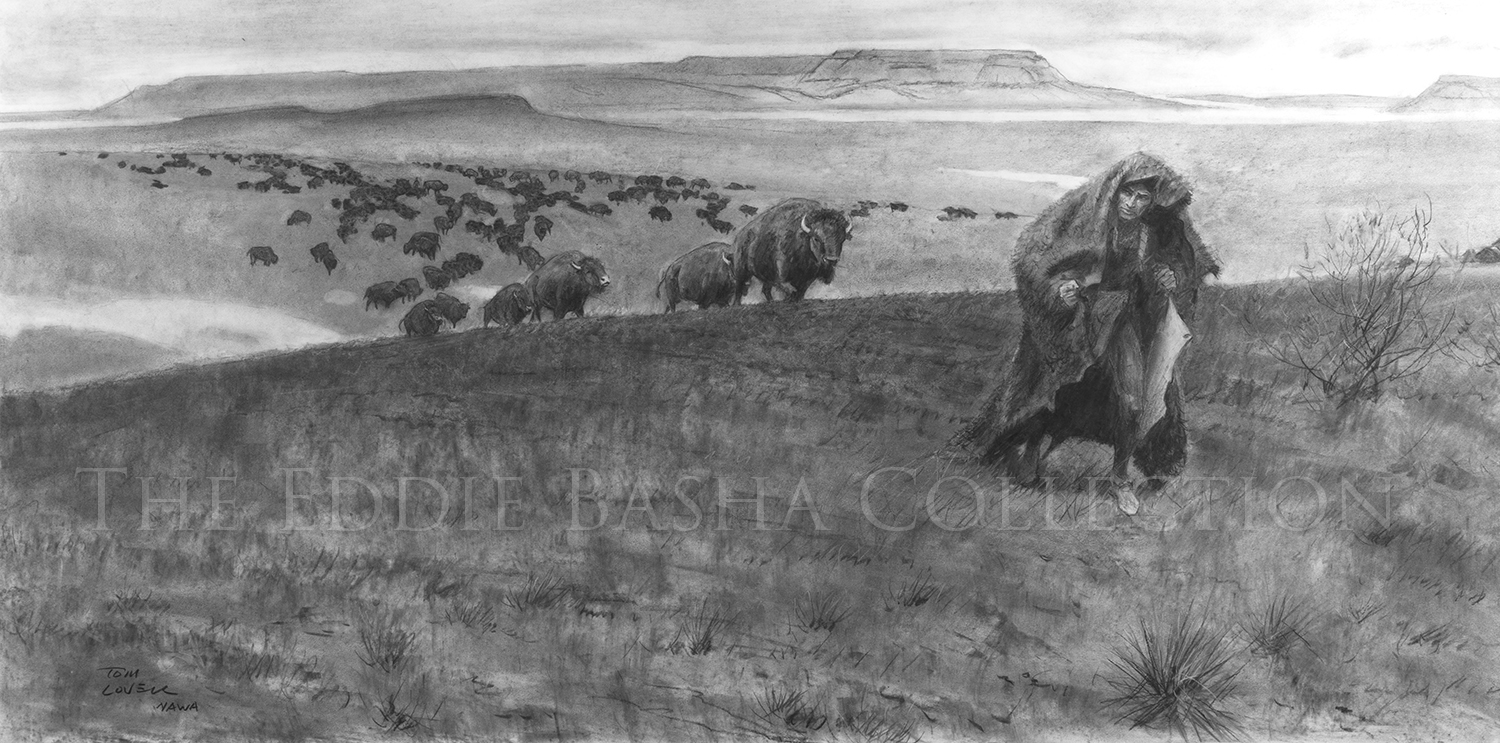

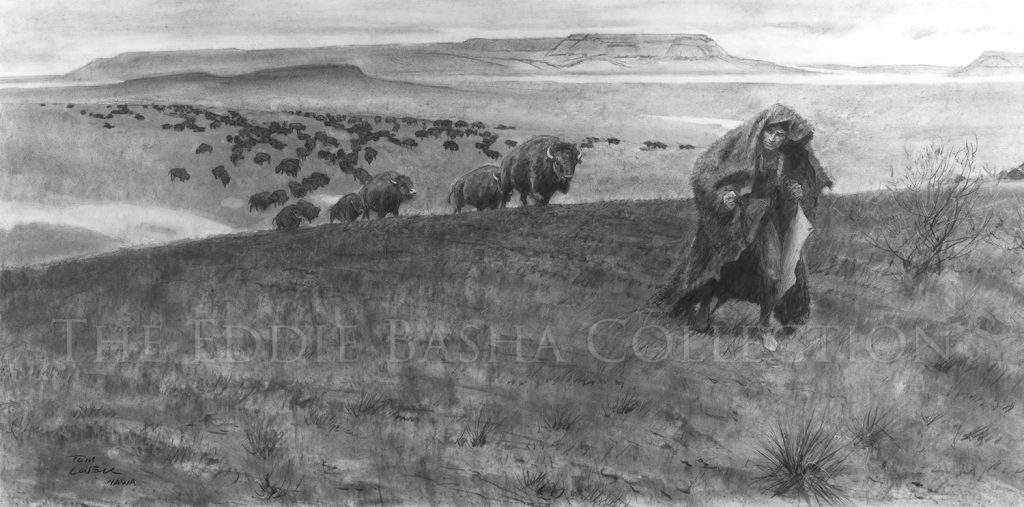

The Buffalo Caller

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Description: Charcoal/Pencil Study | Image Size: 20”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 27 ½” h x 47 ½” wdrawing

Of this piece Tom Lovell wrote, “In the old days before the advent of the white man and the horse, specially trained members of many plains tribes practiced buffalo ‘calling’. The caller, moving on foot under his mantle of buffalo hide, would work his way close to the herd and simulate the sounds of a calf in distress. If successful, several cows would begin to follow and eventually the whole herd would be set in motion and lured into the trap. The trap, a funnel-shaped line of rock and brush piles, led to the brink of a cliff. Once within the jaws of the trap, the caller would make his exit to one side and the villagers who had been lying in wait would spring up with yells and robe waving, stampeding the herd over the brink. Even after the acquisition of the horse, some callers continued to work on foot as shown.”

This is a fine example of Lovell’s practice of making a large preparatory drawing that he would later match with a finished colored oil of the same size. For this particular piece, he produced smaller studies of the primary figure in charcoal as well. Although the drawing was done as a model for the oil, it contains all of the elements that will be found in the final painting. Many artists use thumbnail sketches, smaller drawings, or drawings that merely outline what will appear in the final painting. Lovell, however, preferred to do a one to one match of drawing and oil in terms of detail and size.

Into the Eye of the Sun

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Description: Oil (1996) | Image Size: 22” x 34”; Framed Size: 33“h x 45“wpainting

As someone with a keen interest in the history of the Native People of the Great Plains, Tom Lovell read numerous accounts of the daily lives, customs, and practices of many tribes. As an artist and visual storyteller, he was able to apply that research to create paintings that bring those historical accounts to life. Here, his depiction of two Sioux scouts peering into the morning sun to gauge the numbers and movement of a distant buffalo herd allows the viewer an opportunity to immerse himself in another time and place. Paintings such as this one, with their authentic details of clothing and weaponry, the realistic depiction of the landscape—seen here as a vast expanse of prairie and distant mountains, and the great attention to detail, make historical research inviting. In this painting, Lovell demonstrates the thoroughness of an historian, the skill of an artist—note the long shadows stretching behind the Indians denoting an early morning timeframe, and the nuances of a gifted storyteller exemplified by one of the scouts utilizing his shield as a screen against the bright rays of the sun.

Long Time Till New Grass

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Description: Charcoal and Pencil | Image Size: 20”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 27”h x 46 ½”wpainting

Pastel | Image Size: 9”h x 16”w; Framed Size: 17”h x 24 ½”w

Oil (1982) | Image Size: 20”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 31”h x 51”w

It is rare for a single collection to contain the finished oil painting, a same-size charcoal and pencil study, as well as a pastel study of the same scene. Studying all three affords a great opportunity to get an insight into the creative process that Tom Lovell used. Preparatory drawings such as these are often used by artists to work out composition details and to fine tune the unfolding narrative that the scene reveals; they are the blueprint for the oil that is to follow. Once the artist is satisfied with his scene, he can adapt it to oil paints utilizing a full range of colors and incorporating texture.

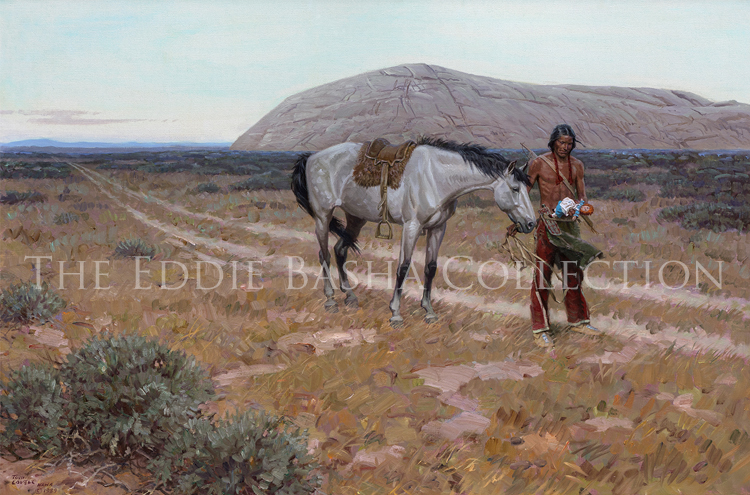

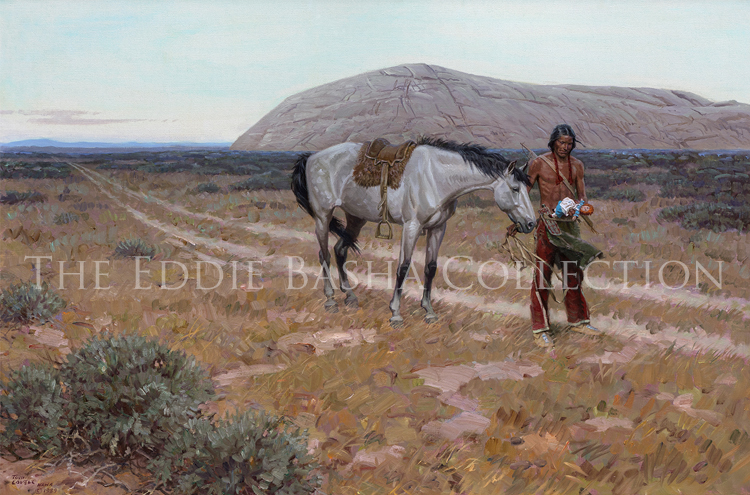

The Lost Rag Doll

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Description: Oil (1989) | Image Size: 24”h x 36”w; Framed Size: 36“h x 48“wpainting

Wagon tracks had become a permanent feature of the prairie landscape in the 1840’s as increasing numbers of immigrants traveled the Oregon Trail. From the shelter of the hills, Indians observed the exodus and wondered where the people came from and where they were headed. In the lodges of the chiefs, men sat around council fires and talked of the trespassers who were disturbing the buffalo.

Near Independence Rock, a Cheyenne brave rode down to investigate a bright spot of color beside the dusty track. He found a child's doll, a plaything not so different from one made of buckskin that belonged to his own daughter. He thought that maybe the prairie travelers were not truly terrible people as some said; cold hearts would not make redheaded dolls for little girls to play with. Perhaps the warnings of the shaman had been wrong, and the wagons would continue to pass in peace.

Sometimes a painting can tell an entire story just with the inclusion of a single, small detail. In this case, the detail is a rag doll that is both an artistic and literary device designed to engage the imagination of the viewer. The wagon tracks stretch behind the warrior beyond the far horizon and continue in front of him outside of the painting’s right edge. Cowboy Artists of America member, Tom Lovell, used a palette of dull browns, tans, and greens, providing a realistic feel to the barren landscape. The flat landscape is interrupted by a butte that rises in the background behind the warrior.

An image of “The Lost Rag Doll” appears in the book entitled “The Art of Tom Lovell: An Invitation to History” authored by Don Hedgpeth and Walt Reed; published by Greenwich Workshop in 1993.

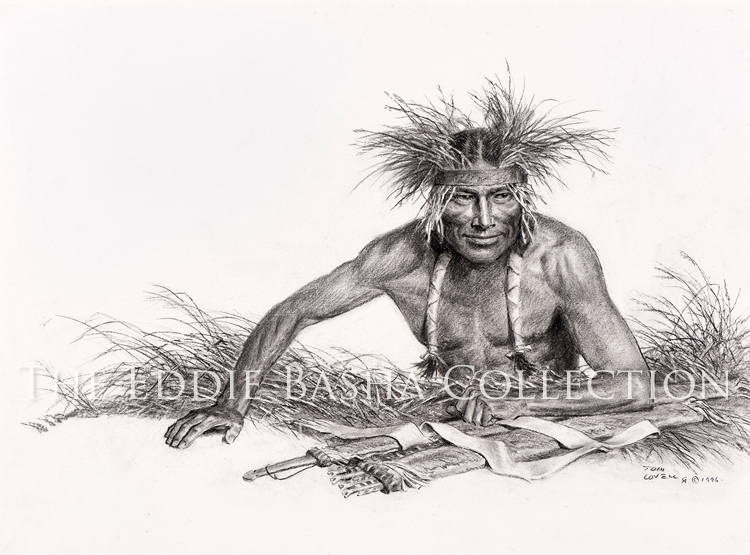

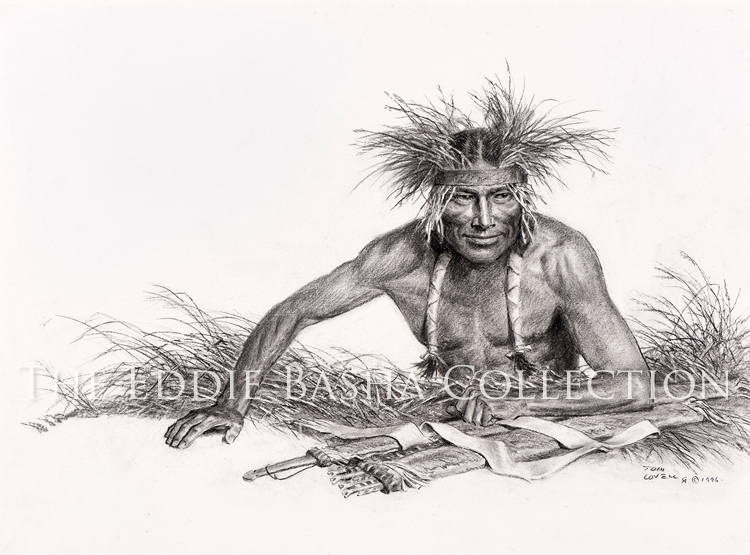

Lakota, Tuft of Grass

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Description: Charcoal (1996) | Image Size: 18”h x 24”w; Framed Size: 24 ¾”h x 30 7/8”wdrawing

A scout’s task was to observe, gather information and withdraw unseen. His black hair was a problem, and in grassy country the obvious solution was to tie bunches of grass around his head and become one with the landscape.

The bow and quiver of arrows placed in front of the figure are also historically accurate to the period, substantiating Tom Lovell’s knowledge of Native American history and customs.

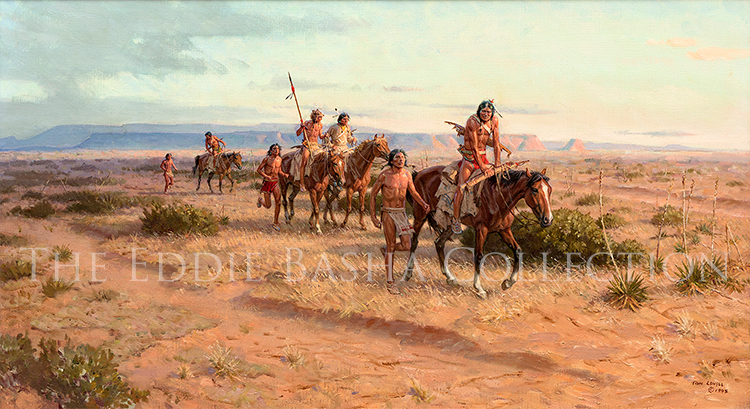

First Horses for the Brulé Sioux

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Description: Oil (1995) | Image Size: 20”h x 36”w; Framed Size: 30"h x 46"wpainting

During the 1770’s, a small party of young Sioux made a trading journey to the Southland and saw horses for the first time. They exchanged all their trade goods for several of the wonderful creatures and took turns riding and running alongside on their way home. Upon their return, tribal elders and family members mocked their sunburned thighs, earning them the name Brulé Cuisse, French for sunburned thighs. The name stuck and the introduction of the horse to the Sioux changed lives forever. Cowboy Artists of America Member, Tom Lovell, unveiled this piece at the 1995 Prix de West Exhibition held at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

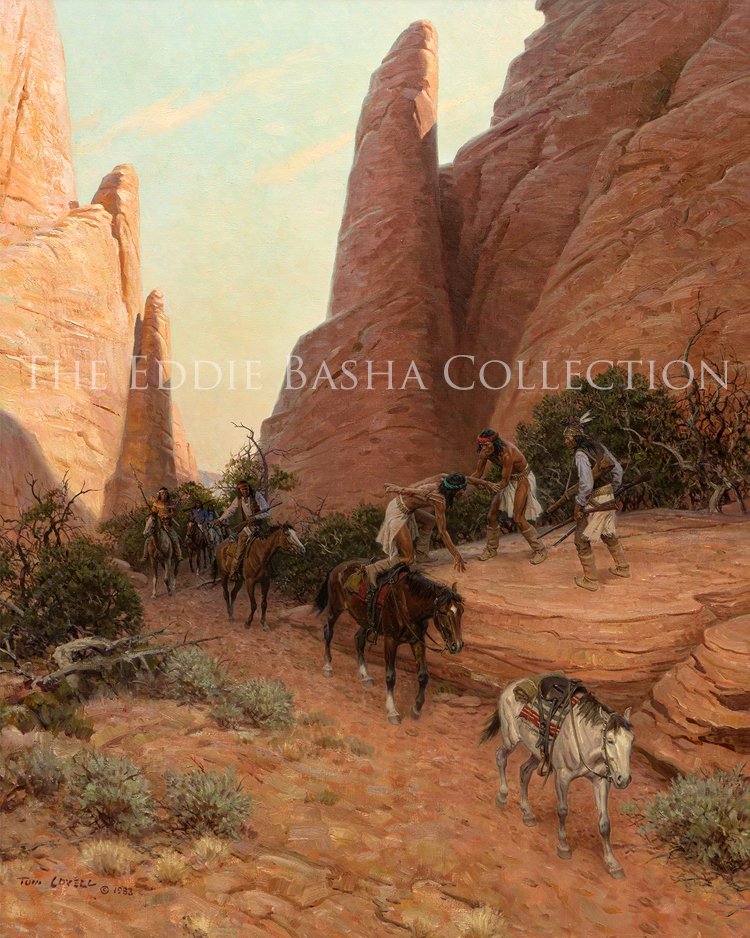

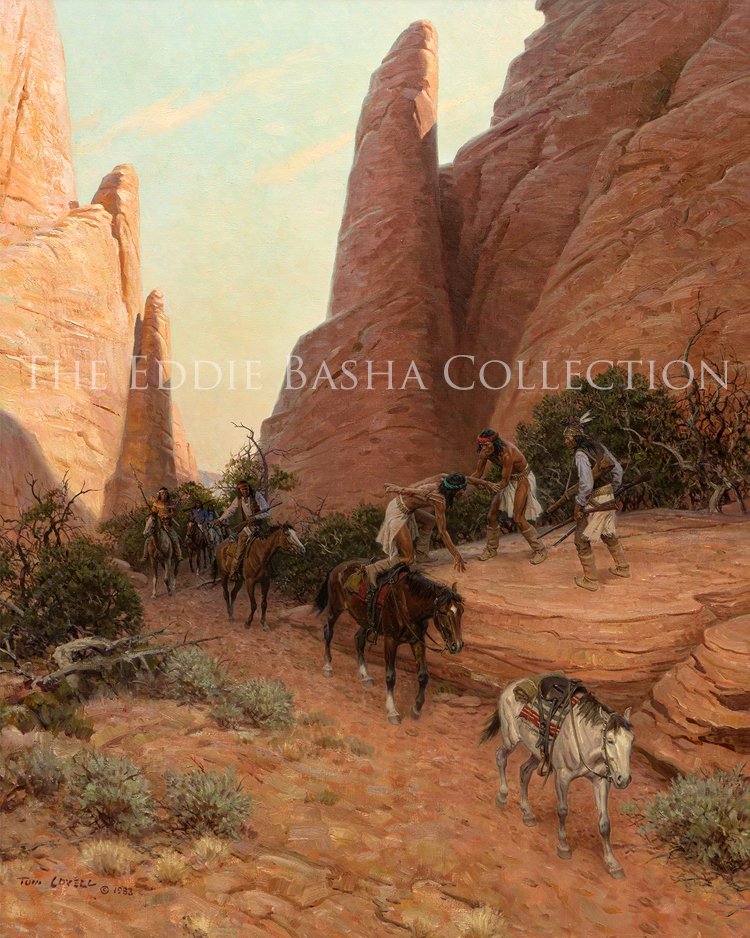

Pony Tracks & Empty Saddles

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Description: Oil (1983) | Image Size: 40”h x 32”w; Framed Size: 51”h x 43”wpainting

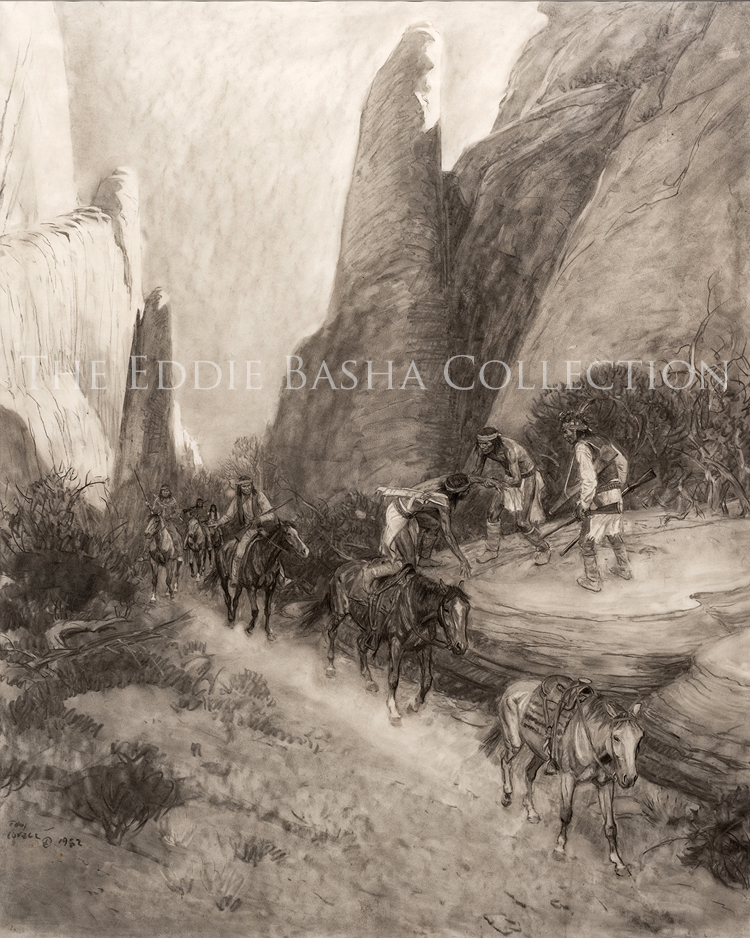

In the book entitled “The Art of Tom Lovell: An Invitation To History,” published by Greenwich Workshop in 1993, authored by Don Hedgpeth and Walt Reed, an image of this painting appears as does the following narrative: “The element of surprise was a major weapon in the arsenal of the Apache. They struck their enemies in lightning-swift raids and withdrew as suddenly. If pursued, they prepared ambushes in narrow, rocky canyons to deal a second deadly blow. In this scene, the rear guard has reported such a pursuing force. Some warriors drop off at strategic points along the canyon, while others continue on with the horses, leaving tracks which will make it appear that the raiders are still in retreat. The enemy of the Apache would learn to fear places like this where steep rock walls blocked out the sun and death waited in the shadows. One such place came to be known as Apache Pass, a narrow six-mile-long canyon between the Dragoon and Chiricahua Mountains in southeastern Arizona. Spaniards, Mexicans and Americans learned about guerrilla warfare, the hard way, on the dim trail that led through Apache Pass.”

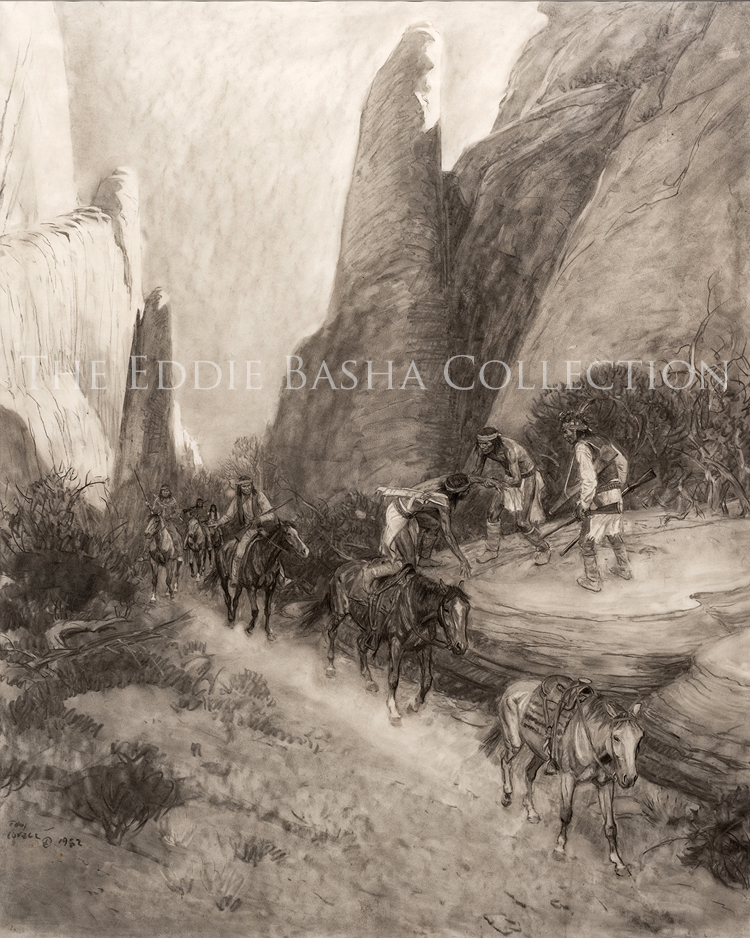

Pony Tracks & Empty Saddles

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Description: Pencil Study (1982) | Image Size: 40”h x 31”w; Framed Size: 48”h x 39”wdrawing

In the book entitled “The Art of Tom Lovell: An Invitation To History,” published by Greenwich Workshop in 1993, authored by Don Hedgpeth and Walt Reed, an image of this painting appears as does the following narrative: “The element of surprise was a major weapon in the arsenal of the Apache. They struck their enemies in lightning-swift raids and withdrew as suddenly. If pursued, they prepared ambushes in narrow, rocky canyons to deal a second deadly blow. In this scene, the rear guard has reported such a pursuing force. Some warriors drop off at strategic points along the canyon, while others continue on with the horses, leaving tracks which will make it appear that the raiders are still in retreat. The enemy of the Apache would learn to fear places like this where steep rock walls blocked out the sun and death waited in the shadows. One such place came to be known as Apache Pass, a narrow six-mile-long canyon between the Dragoon and Chiricahua Mountains in southeastern Arizona. Spaniards, Mexicans and Americans learned about guerrilla warfare, the hard way, on the dim trail that led through Apache Pass.”

The Deceiver

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Description: Oil (1976) | Image Size: 20”h x 36”w; Framed Size: 29”h x 45”wpainting

Traditional military training and strategy were no match for the unconventional guerrilla tactics of the wild Apache. Battle-scarred veterans of the Apache wars, from the merciless Jose Carrasco of Sonora to the American Generals George Crook and Nelson A. Miles came to admit reluctantly their respect for the devils of the desert. They realized that there was an intuitive quality to the Apache concept of war. Like the wolf, an Apache knew instinctively when to fight and when to flee, where to hide, and how to travel fast and far across terrain unknown to the enemy.

In this scene, Apache raiders are attempting to lure a cavalry patrol into an ambush with the help of a souvenir from an earlier victory. Swift and certain death awaits the soldiers who respond to the deceptive clarion call. Shadows deepen as the sun drops below the surrounding mesas. Life and death hang in the balance as darkness descends. Narrative extrapolated from The Art of Tom Lovell: An Invitation To History, authored by Don Hedgpeth and Walt Reed, and published by Greenwich Workshop in 1993.

“The Deceiver” won the Gold Medal in Oil at the 11th Annual Cowboy Artists of America Show & Sale in 1976 at the Phoenix Art Museum. It should be noted that 1976 was the first year Tom Lovell participated as an artist in a CAA Show & Sale; not bad for a rookie member at the time! Subsequently, this masterwork has been exhibited at the “Clymer, Lovell & Teague” exhibition at the Thomas Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, OK; the “Grand Opening Exhibition” of the CAA Museum in Kerrville, TX; the “West-Southwest Exhibit” at the Albuquerque Museum of Art, History & Science; and at “A Salute to CAA and a Patron, the late Eddie Basha: 50 Years of Amazing Contributions to the American West” in 2016 at Western Spirit Scottsdale’s Museum of the West.

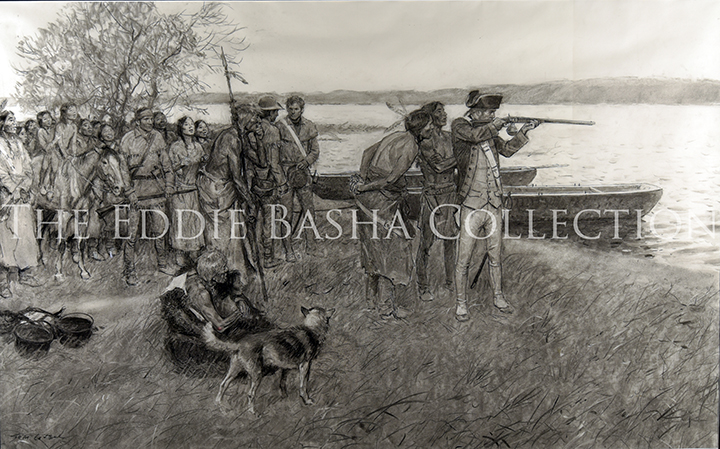

Captain Clark’s Air Gun (Study)

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Description: 24”h x 38”wpainting

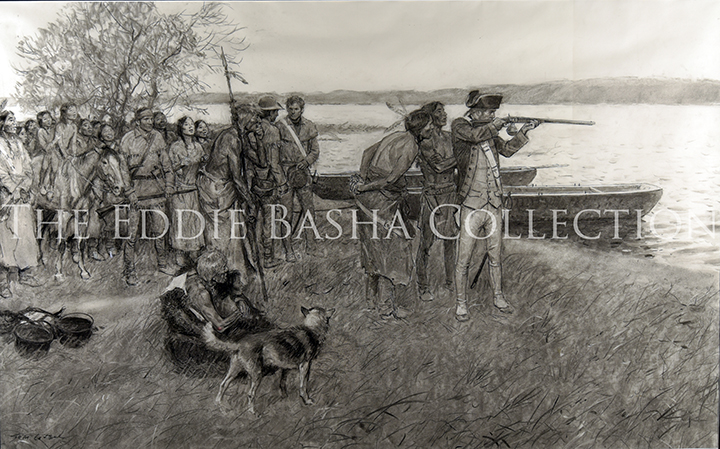

Most Indians living along the twisting course of the upper Missouri River had not seen white men prior to the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804-1806. A few scruffy French voyagers had come down from Canada to trade with villages on the northeastern edge of the Plains, but the arrival of the Lewis and Clark party was the first time a significant number of Indians came in contact with this tribe of men who appeared so different from themselves. Great excitement was created by the arrival of these strange visitors from the East. The manner of dress of the expedition commanders was most unusual, and they brought with them things which inspired awe.

Part of the mission of the Corps of Discovery was to make friends of the native people encountered on the long journey to the Pacific. Here, Captain Clark, in full dress uniform, entertains a band of Indians with a demonstration of a rifle which fires multiple times from the power of a compressed air flask attached beneath the breech.

Pencil Study | Image Size: 28 3/8”h x 24 3/8”w; Framed Size: 38 3/8”h x 34 3/8”w

Pencil Study | Image Size: 28 3/8”h x 24 3/8”w; Framed Size: 38 3/8”h x 34 3/8”wTwo men who became among the country’s most acclaimed magazine illustrators of their time and went on to equally illustrious careers as western artists, Tom Lovell and John Clymer, went through boot camp together and served their country during World War II. The idea for this drawing came from their shared boot camp experience at Parris Island where, with 80 men in a barracks, if anyone caught a cold, everyone shared it. John obligingly posed for it and Tom made it the subject of a Leatherneck cover.

Lovell gifted the original study to Eddie Basha in 1982. It was subsequently loaned to Western Spirit Scottsdale’s Museum of the West for the exhibition entitled “A Salute to Cowboy Artists of America and a Patron, the late Eddie Basha: 50 Years of Amazing Contributions to the American West” (Nov 2015 – May 2016) and an image of the original oil appeared in the book entitled “The Art of Tom Lovell: An Invitation to History” authored by Don Hedgpeth and Walt Reed and published by Greenwich Workshop in 1993

Throat Spray M1 (Study)

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Two men who became among the country’s most acclaimed magazine illustrators of their time and went on to equally illustrious careers as western artists, Tom Lovell and John Clymer, went through boot camp together and served their country during World War II. The idea for this drawing came from their shared boot camp experience at Parris Island where, with 80 men in a barracks, if anyone caught a cold, everyone shared it. John obligingly posed for it and Tom made it the subject of a Leatherneck cover.

Lovell gifted the original study to Eddie Basha in 1982. It was subsequently loaned to Western Spirit Scottsdale’s Museum of the West for the exhibition entitled “A Salute to Cowboy Artists of America and a Patron, the late Eddie Basha: 50 Years of Amazing Contributions to the American West” (Nov 2015 – May 2016) and an image of the original oil appeared in the book entitled “The Art of Tom Lovell: An Invitation to History” authored by Don Hedgpeth and Walt Reed and published by Greenwich Workshop in 1993

Charcoal/Pencil (1990) | Image Size: 20”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 27“h x 47“w

Charcoal/Pencil (1990) | Image Size: 20”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 27“h x 47“wAlthough he often painted stories of important historic events, Tom Lovell also offered visual tales of everyday life of particular historic periods. He was a great student of American Indian history and created interesting and sometimes humorous scenes based on his research. In this study for an oil painting, he shows a young Indian leading a group of children through a small teepee village. The children seem captivated by the fact that their leader is sitting on his horse backwards. The viewer of the painting focuses on the progression of the rider as he passes the tipis riding from the left to the right edge of the canvas. Children, women, and dogs are shown trailing this unusual rider.

Contrary One

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Although he often painted stories of important historic events, Tom Lovell also offered visual tales of everyday life of particular historic periods. He was a great student of American Indian history and created interesting and sometimes humorous scenes based on his research. In this study for an oil painting, he shows a young Indian leading a group of children through a small teepee village. The children seem captivated by the fact that their leader is sitting on his horse backwards. The viewer of the painting focuses on the progression of the rider as he passes the tipis riding from the left to the right edge of the canvas. Children, women, and dogs are shown trailing this unusual rider.

Oil (1975) | Image Size: 23”h x 41”w; Framed Size: 32”h x 50”w

Oil (1975) | Image Size: 23”h x 41”w; Framed Size: 32”h x 50”wIn the book The Art of Tom Lovell: An Invitation to History authored by Don Hedgpeth and Walt Reed, an image of this painting appears. The narrative provided reads “Death was a major preoccupation for the Apache. The dead were buried quickly and their possessions burned. Mourners moved their camp away from the place of death. Spirits and ghosts dwelled everywhere in the Apache's world. The owl was thought to be a messenger of death, a harbinger of disaster. When an Apache camp was struck by pestilence, mud effigies of the owl were placed along trails leading to the camp as a warning. Here a group of warriors returning after days on the trail, spot a mud owl and stop to ponder its meaning as the sun's last rays strike the distant mesa.”

The Mud Owl’s Warning

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

In the book The Art of Tom Lovell: An Invitation to History authored by Don Hedgpeth and Walt Reed, an image of this painting appears. The narrative provided reads “Death was a major preoccupation for the Apache. The dead were buried quickly and their possessions burned. Mourners moved their camp away from the place of death. Spirits and ghosts dwelled everywhere in the Apache's world. The owl was thought to be a messenger of death, a harbinger of disaster. When an Apache camp was struck by pestilence, mud effigies of the owl were placed along trails leading to the camp as a warning. Here a group of warriors returning after days on the trail, spot a mud owl and stop to ponder its meaning as the sun's last rays strike the distant mesa.”

Oil | Image Size: 20 ½”h x 33”w; Framed Size: 30”h x 43”w

Oil | Image Size: 20 ½”h x 33”w; Framed Size: 30”h x 43”wEarly accounts tell us every fall that in the month of September, Comanche war parties would regularly make the long journey to raid the scattered ranches below the Rio Grande. This was the best time of year to travel because the waterholes and streams were more likely to be filled and thus parties’ tracks would be indiscernible. Comanche war parties always departed at night, and followed streams whenever practical. September became known in West Texas as the Comanche Moon.

This evocative painting of a Comanche war party traveling down a shallow stream bed under a bright moon displays Tom Lovell’s full talent as an artist and storyteller. Every element of the painting is expertly crafted from the ripples in the stream to the moonlit sandy ground beneath the horses’ feet. Lovell has masterfully depicted the moonlight that is so bright and clear that the surrounding landscape is revealed in detail. The riders progress toward the viewer in single file. Two warriors ride at the head of the column while the last rider is placed in the far background enhancing the sense of distance covered by the party. Painting water realistically is a difficult task even for the most accomplished artists and Lovell’s skill in doing so is amply evident in his stream depiction with its undulating ripples. As befitting a scene of nighttime travel, the painting evokes a sense of quiet peacefulness. In terms of the story being told of Comanche warriors en route to a raid on settlers or another Indian tribe, this quiet scene stands in sharp contrast to what will occur once these riders have passed from our viewpoint. Lovell has taken a common frontier narrative, one of conflict, drama, and action, and has chosen to present a different aspect of that account. His scene is quiet and nuanced, subsequent scenes in this tale will be quite different.

Comanche Moon

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Early accounts tell us every fall that in the month of September, Comanche war parties would regularly make the long journey to raid the scattered ranches below the Rio Grande. This was the best time of year to travel because the waterholes and streams were more likely to be filled and thus parties’ tracks would be indiscernible. Comanche war parties always departed at night, and followed streams whenever practical. September became known in West Texas as the Comanche Moon.

This evocative painting of a Comanche war party traveling down a shallow stream bed under a bright moon displays Tom Lovell’s full talent as an artist and storyteller. Every element of the painting is expertly crafted from the ripples in the stream to the moonlit sandy ground beneath the horses’ feet. Lovell has masterfully depicted the moonlight that is so bright and clear that the surrounding landscape is revealed in detail. The riders progress toward the viewer in single file. Two warriors ride at the head of the column while the last rider is placed in the far background enhancing the sense of distance covered by the party. Painting water realistically is a difficult task even for the most accomplished artists and Lovell’s skill in doing so is amply evident in his stream depiction with its undulating ripples. As befitting a scene of nighttime travel, the painting evokes a sense of quiet peacefulness. In terms of the story being told of Comanche warriors en route to a raid on settlers or another Indian tribe, this quiet scene stands in sharp contrast to what will occur once these riders have passed from our viewpoint. Lovell has taken a common frontier narrative, one of conflict, drama, and action, and has chosen to present a different aspect of that account. His scene is quiet and nuanced, subsequent scenes in this tale will be quite different.

Charcoal/Pencil | Image Size: 18”h x 30”w; Framed Size: 25”h x 37”w

Charcoal/Pencil | Image Size: 18”h x 30”w; Framed Size: 25”h x 37”wIn the book “The Art of Tom Lovell: An Invitation To History” published by Greenwich Workshop in 1993, authored by Don Hedgpeth and Walt Reed, the following was written about “Wrong Side Up”.

“What manner of men were these white people who would do such a thing to the buffalo range? The plow proved to be a deadly weapon which set in motion a sequence of destruction. Crops were planted where the buffalo had grazed; soon the great herds would be gone. Without the buffalo, the Indian was doomed. And in the end, the white farmers would abandon these places to drought and erosion, the genesis of the dust bowl days. Buffalo, Indians, homesteaders... all blown away in the rising dust clouds because the land had been turned wrong side up.

The scars are still upon the land, and deepest yet in the hearts of the descendants of Plains Indians who had understood the delicate balance of nature on the range of the buffalo.”

In this simple drawing, simple in terms of composition but complex in terms of meaning, Lovell’s prowess as a storyteller who could paint scenes from many different points of view is highlighted.

Wrong Side Up Study

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

In the book “The Art of Tom Lovell: An Invitation To History” published by Greenwich Workshop in 1993, authored by Don Hedgpeth and Walt Reed, the following was written about “Wrong Side Up”.

“What manner of men were these white people who would do such a thing to the buffalo range? The plow proved to be a deadly weapon which set in motion a sequence of destruction. Crops were planted where the buffalo had grazed; soon the great herds would be gone. Without the buffalo, the Indian was doomed. And in the end, the white farmers would abandon these places to drought and erosion, the genesis of the dust bowl days. Buffalo, Indians, homesteaders... all blown away in the rising dust clouds because the land had been turned wrong side up.

The scars are still upon the land, and deepest yet in the hearts of the descendants of Plains Indians who had understood the delicate balance of nature on the range of the buffalo.”

In this simple drawing, simple in terms of composition but complex in terms of meaning, Lovell’s prowess as a storyteller who could paint scenes from many different points of view is highlighted.

Charcoal & Pencil (1976) | Image Size: 22”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 29”h x 47”w

Charcoal & Pencil (1976) | Image Size: 22”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 29”h x 47”wThe Recruiter (Drawing)

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Oil (1974) | Image Size: 22”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 32”h x 49”w

Oil (1974) | Image Size: 22”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 32”h x 49”wThe Piegan were a northern tribe, a branch of the Blackfeet. Pioneer photographer and historian, Edward Curtis, related when speaking of their customs that “when a successful warrior wanted to lead a war party he caught his best horse, held his gun high above his head and rode around the camp singing a war song. It was a signal for all who wanted to follow him to start repairing their weapons and moccasins. On the following morning the leader saddled, rode away and assembled the men on a nearby hill."

The Recruiter

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

The Piegan were a northern tribe, a branch of the Blackfeet. Pioneer photographer and historian, Edward Curtis, related when speaking of their customs that “when a successful warrior wanted to lead a war party he caught his best horse, held his gun high above his head and rode around the camp singing a war song. It was a signal for all who wanted to follow him to start repairing their weapons and moccasins. On the following morning the leader saddled, rode away and assembled the men on a nearby hill."

Charcoal/Pencil Study | Image Size: 20”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 27 ½” h x 47 ½” w

Charcoal/Pencil Study | Image Size: 20”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 27 ½” h x 47 ½” wOf this piece Tom Lovell wrote, “In the old days before the advent of the white man and the horse, specially trained members of many plains tribes practiced buffalo ‘calling’. The caller, moving on foot under his mantle of buffalo hide, would work his way close to the herd and simulate the sounds of a calf in distress. If successful, several cows would begin to follow and eventually the whole herd would be set in motion and lured into the trap. The trap, a funnel-shaped line of rock and brush piles, led to the brink of a cliff. Once within the jaws of the trap, the caller would make his exit to one side and the villagers who had been lying in wait would spring up with yells and robe waving, stampeding the herd over the brink. Even after the acquisition of the horse, some callers continued to work on foot as shown.”

This is a fine example of Lovell’s practice of making a large preparatory drawing that he would later match with a finished colored oil of the same size. For this particular piece, he produced smaller studies of the primary figure in charcoal as well. Although the drawing was done as a model for the oil, it contains all of the elements that will be found in the final painting. Many artists use thumbnail sketches, smaller drawings, or drawings that merely outline what will appear in the final painting. Lovell, however, preferred to do a one to one match of drawing and oil in terms of detail and size.

The Buffalo Caller

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Of this piece Tom Lovell wrote, “In the old days before the advent of the white man and the horse, specially trained members of many plains tribes practiced buffalo ‘calling’. The caller, moving on foot under his mantle of buffalo hide, would work his way close to the herd and simulate the sounds of a calf in distress. If successful, several cows would begin to follow and eventually the whole herd would be set in motion and lured into the trap. The trap, a funnel-shaped line of rock and brush piles, led to the brink of a cliff. Once within the jaws of the trap, the caller would make his exit to one side and the villagers who had been lying in wait would spring up with yells and robe waving, stampeding the herd over the brink. Even after the acquisition of the horse, some callers continued to work on foot as shown.”

This is a fine example of Lovell’s practice of making a large preparatory drawing that he would later match with a finished colored oil of the same size. For this particular piece, he produced smaller studies of the primary figure in charcoal as well. Although the drawing was done as a model for the oil, it contains all of the elements that will be found in the final painting. Many artists use thumbnail sketches, smaller drawings, or drawings that merely outline what will appear in the final painting. Lovell, however, preferred to do a one to one match of drawing and oil in terms of detail and size.

Oil (1996) | Image Size: 22” x 34”; Framed Size: 33“h x 45“w

Oil (1996) | Image Size: 22” x 34”; Framed Size: 33“h x 45“wAs someone with a keen interest in the history of the Native People of the Great Plains, Tom Lovell read numerous accounts of the daily lives, customs, and practices of many tribes. As an artist and visual storyteller, he was able to apply that research to create paintings that bring those historical accounts to life. Here, his depiction of two Sioux scouts peering into the morning sun to gauge the numbers and movement of a distant buffalo herd allows the viewer an opportunity to immerse himself in another time and place. Paintings such as this one, with their authentic details of clothing and weaponry, the realistic depiction of the landscape—seen here as a vast expanse of prairie and distant mountains, and the great attention to detail, make historical research inviting. In this painting, Lovell demonstrates the thoroughness of an historian, the skill of an artist—note the long shadows stretching behind the Indians denoting an early morning timeframe, and the nuances of a gifted storyteller exemplified by one of the scouts utilizing his shield as a screen against the bright rays of the sun.

Into the Eye of the Sun

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

As someone with a keen interest in the history of the Native People of the Great Plains, Tom Lovell read numerous accounts of the daily lives, customs, and practices of many tribes. As an artist and visual storyteller, he was able to apply that research to create paintings that bring those historical accounts to life. Here, his depiction of two Sioux scouts peering into the morning sun to gauge the numbers and movement of a distant buffalo herd allows the viewer an opportunity to immerse himself in another time and place. Paintings such as this one, with their authentic details of clothing and weaponry, the realistic depiction of the landscape—seen here as a vast expanse of prairie and distant mountains, and the great attention to detail, make historical research inviting. In this painting, Lovell demonstrates the thoroughness of an historian, the skill of an artist—note the long shadows stretching behind the Indians denoting an early morning timeframe, and the nuances of a gifted storyteller exemplified by one of the scouts utilizing his shield as a screen against the bright rays of the sun.

Charcoal and Pencil | Image Size: 20”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 27”h x 46 ½”w

Charcoal and Pencil | Image Size: 20”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 27”h x 46 ½”wPastel | Image Size: 9”h x 16”w; Framed Size: 17”h x 24 ½”w

Oil (1982) | Image Size: 20”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 31”h x 51”w

It is rare for a single collection to contain the finished oil painting, a same-size charcoal and pencil study, as well as a pastel study of the same scene. Studying all three affords a great opportunity to get an insight into the creative process that Tom Lovell used. Preparatory drawings such as these are often used by artists to work out composition details and to fine tune the unfolding narrative that the scene reveals; they are the blueprint for the oil that is to follow. Once the artist is satisfied with his scene, he can adapt it to oil paints utilizing a full range of colors and incorporating texture.

Long Time Till New Grass

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Pastel | Image Size: 9”h x 16”w; Framed Size: 17”h x 24 ½”w

Oil (1982) | Image Size: 20”h x 40”w; Framed Size: 31”h x 51”w

It is rare for a single collection to contain the finished oil painting, a same-size charcoal and pencil study, as well as a pastel study of the same scene. Studying all three affords a great opportunity to get an insight into the creative process that Tom Lovell used. Preparatory drawings such as these are often used by artists to work out composition details and to fine tune the unfolding narrative that the scene reveals; they are the blueprint for the oil that is to follow. Once the artist is satisfied with his scene, he can adapt it to oil paints utilizing a full range of colors and incorporating texture.

Oil (1989) | Image Size: 24”h x 36”w; Framed Size: 36“h x 48“w

Oil (1989) | Image Size: 24”h x 36”w; Framed Size: 36“h x 48“wWagon tracks had become a permanent feature of the prairie landscape in the 1840’s as increasing numbers of immigrants traveled the Oregon Trail. From the shelter of the hills, Indians observed the exodus and wondered where the people came from and where they were headed. In the lodges of the chiefs, men sat around council fires and talked of the trespassers who were disturbing the buffalo.

Near Independence Rock, a Cheyenne brave rode down to investigate a bright spot of color beside the dusty track. He found a child's doll, a plaything not so different from one made of buckskin that belonged to his own daughter. He thought that maybe the prairie travelers were not truly terrible people as some said; cold hearts would not make redheaded dolls for little girls to play with. Perhaps the warnings of the shaman had been wrong, and the wagons would continue to pass in peace.

Sometimes a painting can tell an entire story just with the inclusion of a single, small detail. In this case, the detail is a rag doll that is both an artistic and literary device designed to engage the imagination of the viewer. The wagon tracks stretch behind the warrior beyond the far horizon and continue in front of him outside of the painting’s right edge. Cowboy Artists of America member, Tom Lovell, used a palette of dull browns, tans, and greens, providing a realistic feel to the barren landscape. The flat landscape is interrupted by a butte that rises in the background behind the warrior.

An image of “The Lost Rag Doll” appears in the book entitled “The Art of Tom Lovell: An Invitation to History” authored by Don Hedgpeth and Walt Reed; published by Greenwich Workshop in 1993.

The Lost Rag Doll

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Wagon tracks had become a permanent feature of the prairie landscape in the 1840’s as increasing numbers of immigrants traveled the Oregon Trail. From the shelter of the hills, Indians observed the exodus and wondered where the people came from and where they were headed. In the lodges of the chiefs, men sat around council fires and talked of the trespassers who were disturbing the buffalo.

Near Independence Rock, a Cheyenne brave rode down to investigate a bright spot of color beside the dusty track. He found a child's doll, a plaything not so different from one made of buckskin that belonged to his own daughter. He thought that maybe the prairie travelers were not truly terrible people as some said; cold hearts would not make redheaded dolls for little girls to play with. Perhaps the warnings of the shaman had been wrong, and the wagons would continue to pass in peace.

Sometimes a painting can tell an entire story just with the inclusion of a single, small detail. In this case, the detail is a rag doll that is both an artistic and literary device designed to engage the imagination of the viewer. The wagon tracks stretch behind the warrior beyond the far horizon and continue in front of him outside of the painting’s right edge. Cowboy Artists of America member, Tom Lovell, used a palette of dull browns, tans, and greens, providing a realistic feel to the barren landscape. The flat landscape is interrupted by a butte that rises in the background behind the warrior.

An image of “The Lost Rag Doll” appears in the book entitled “The Art of Tom Lovell: An Invitation to History” authored by Don Hedgpeth and Walt Reed; published by Greenwich Workshop in 1993.

Charcoal (1996) | Image Size: 18”h x 24”w; Framed Size: 24 ¾”h x 30 7/8”w

Charcoal (1996) | Image Size: 18”h x 24”w; Framed Size: 24 ¾”h x 30 7/8”wA scout’s task was to observe, gather information and withdraw unseen. His black hair was a problem, and in grassy country the obvious solution was to tie bunches of grass around his head and become one with the landscape.

The bow and quiver of arrows placed in front of the figure are also historically accurate to the period, substantiating Tom Lovell’s knowledge of Native American history and customs.

Lakota, Tuft of Grass

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

A scout’s task was to observe, gather information and withdraw unseen. His black hair was a problem, and in grassy country the obvious solution was to tie bunches of grass around his head and become one with the landscape.

The bow and quiver of arrows placed in front of the figure are also historically accurate to the period, substantiating Tom Lovell’s knowledge of Native American history and customs.

Oil (1995) | Image Size: 20”h x 36”w; Framed Size: 30"h x 46"w

Oil (1995) | Image Size: 20”h x 36”w; Framed Size: 30"h x 46"wDuring the 1770’s, a small party of young Sioux made a trading journey to the Southland and saw horses for the first time. They exchanged all their trade goods for several of the wonderful creatures and took turns riding and running alongside on their way home. Upon their return, tribal elders and family members mocked their sunburned thighs, earning them the name Brulé Cuisse, French for sunburned thighs. The name stuck and the introduction of the horse to the Sioux changed lives forever. Cowboy Artists of America Member, Tom Lovell, unveiled this piece at the 1995 Prix de West Exhibition held at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

First Horses for the Brulé Sioux

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

During the 1770’s, a small party of young Sioux made a trading journey to the Southland and saw horses for the first time. They exchanged all their trade goods for several of the wonderful creatures and took turns riding and running alongside on their way home. Upon their return, tribal elders and family members mocked their sunburned thighs, earning them the name Brulé Cuisse, French for sunburned thighs. The name stuck and the introduction of the horse to the Sioux changed lives forever. Cowboy Artists of America Member, Tom Lovell, unveiled this piece at the 1995 Prix de West Exhibition held at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

Oil (1983) | Image Size: 40”h x 32”w; Framed Size: 51”h x 43”w

Oil (1983) | Image Size: 40”h x 32”w; Framed Size: 51”h x 43”wIn the book entitled “The Art of Tom Lovell: An Invitation To History,” published by Greenwich Workshop in 1993, authored by Don Hedgpeth and Walt Reed, an image of this painting appears as does the following narrative: “The element of surprise was a major weapon in the arsenal of the Apache. They struck their enemies in lightning-swift raids and withdrew as suddenly. If pursued, they prepared ambushes in narrow, rocky canyons to deal a second deadly blow. In this scene, the rear guard has reported such a pursuing force. Some warriors drop off at strategic points along the canyon, while others continue on with the horses, leaving tracks which will make it appear that the raiders are still in retreat. The enemy of the Apache would learn to fear places like this where steep rock walls blocked out the sun and death waited in the shadows. One such place came to be known as Apache Pass, a narrow six-mile-long canyon between the Dragoon and Chiricahua Mountains in southeastern Arizona. Spaniards, Mexicans and Americans learned about guerrilla warfare, the hard way, on the dim trail that led through Apache Pass.”

Pony Tracks & Empty Saddles

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

In the book entitled “The Art of Tom Lovell: An Invitation To History,” published by Greenwich Workshop in 1993, authored by Don Hedgpeth and Walt Reed, an image of this painting appears as does the following narrative: “The element of surprise was a major weapon in the arsenal of the Apache. They struck their enemies in lightning-swift raids and withdrew as suddenly. If pursued, they prepared ambushes in narrow, rocky canyons to deal a second deadly blow. In this scene, the rear guard has reported such a pursuing force. Some warriors drop off at strategic points along the canyon, while others continue on with the horses, leaving tracks which will make it appear that the raiders are still in retreat. The enemy of the Apache would learn to fear places like this where steep rock walls blocked out the sun and death waited in the shadows. One such place came to be known as Apache Pass, a narrow six-mile-long canyon between the Dragoon and Chiricahua Mountains in southeastern Arizona. Spaniards, Mexicans and Americans learned about guerrilla warfare, the hard way, on the dim trail that led through Apache Pass.”

Pencil Study (1982) | Image Size: 40”h x 31”w; Framed Size: 48”h x 39”w

Pencil Study (1982) | Image Size: 40”h x 31”w; Framed Size: 48”h x 39”wIn the book entitled “The Art of Tom Lovell: An Invitation To History,” published by Greenwich Workshop in 1993, authored by Don Hedgpeth and Walt Reed, an image of this painting appears as does the following narrative: “The element of surprise was a major weapon in the arsenal of the Apache. They struck their enemies in lightning-swift raids and withdrew as suddenly. If pursued, they prepared ambushes in narrow, rocky canyons to deal a second deadly blow. In this scene, the rear guard has reported such a pursuing force. Some warriors drop off at strategic points along the canyon, while others continue on with the horses, leaving tracks which will make it appear that the raiders are still in retreat. The enemy of the Apache would learn to fear places like this where steep rock walls blocked out the sun and death waited in the shadows. One such place came to be known as Apache Pass, a narrow six-mile-long canyon between the Dragoon and Chiricahua Mountains in southeastern Arizona. Spaniards, Mexicans and Americans learned about guerrilla warfare, the hard way, on the dim trail that led through Apache Pass.”

Pony Tracks & Empty Saddles

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

In the book entitled “The Art of Tom Lovell: An Invitation To History,” published by Greenwich Workshop in 1993, authored by Don Hedgpeth and Walt Reed, an image of this painting appears as does the following narrative: “The element of surprise was a major weapon in the arsenal of the Apache. They struck their enemies in lightning-swift raids and withdrew as suddenly. If pursued, they prepared ambushes in narrow, rocky canyons to deal a second deadly blow. In this scene, the rear guard has reported such a pursuing force. Some warriors drop off at strategic points along the canyon, while others continue on with the horses, leaving tracks which will make it appear that the raiders are still in retreat. The enemy of the Apache would learn to fear places like this where steep rock walls blocked out the sun and death waited in the shadows. One such place came to be known as Apache Pass, a narrow six-mile-long canyon between the Dragoon and Chiricahua Mountains in southeastern Arizona. Spaniards, Mexicans and Americans learned about guerrilla warfare, the hard way, on the dim trail that led through Apache Pass.”

Oil (1976) | Image Size: 20”h x 36”w; Framed Size: 29”h x 45”w

Oil (1976) | Image Size: 20”h x 36”w; Framed Size: 29”h x 45”wTraditional military training and strategy were no match for the unconventional guerrilla tactics of the wild Apache. Battle-scarred veterans of the Apache wars, from the merciless Jose Carrasco of Sonora to the American Generals George Crook and Nelson A. Miles came to admit reluctantly their respect for the devils of the desert. They realized that there was an intuitive quality to the Apache concept of war. Like the wolf, an Apache knew instinctively when to fight and when to flee, where to hide, and how to travel fast and far across terrain unknown to the enemy.

In this scene, Apache raiders are attempting to lure a cavalry patrol into an ambush with the help of a souvenir from an earlier victory. Swift and certain death awaits the soldiers who respond to the deceptive clarion call. Shadows deepen as the sun drops below the surrounding mesas. Life and death hang in the balance as darkness descends. Narrative extrapolated from The Art of Tom Lovell: An Invitation To History, authored by Don Hedgpeth and Walt Reed, and published by Greenwich Workshop in 1993.

“The Deceiver” won the Gold Medal in Oil at the 11th Annual Cowboy Artists of America Show & Sale in 1976 at the Phoenix Art Museum. It should be noted that 1976 was the first year Tom Lovell participated as an artist in a CAA Show & Sale; not bad for a rookie member at the time! Subsequently, this masterwork has been exhibited at the “Clymer, Lovell & Teague” exhibition at the Thomas Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, OK; the “Grand Opening Exhibition” of the CAA Museum in Kerrville, TX; the “West-Southwest Exhibit” at the Albuquerque Museum of Art, History & Science; and at “A Salute to CAA and a Patron, the late Eddie Basha: 50 Years of Amazing Contributions to the American West” in 2016 at Western Spirit Scottsdale’s Museum of the West.

The Deceiver

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Traditional military training and strategy were no match for the unconventional guerrilla tactics of the wild Apache. Battle-scarred veterans of the Apache wars, from the merciless Jose Carrasco of Sonora to the American Generals George Crook and Nelson A. Miles came to admit reluctantly their respect for the devils of the desert. They realized that there was an intuitive quality to the Apache concept of war. Like the wolf, an Apache knew instinctively when to fight and when to flee, where to hide, and how to travel fast and far across terrain unknown to the enemy.

In this scene, Apache raiders are attempting to lure a cavalry patrol into an ambush with the help of a souvenir from an earlier victory. Swift and certain death awaits the soldiers who respond to the deceptive clarion call. Shadows deepen as the sun drops below the surrounding mesas. Life and death hang in the balance as darkness descends. Narrative extrapolated from The Art of Tom Lovell: An Invitation To History, authored by Don Hedgpeth and Walt Reed, and published by Greenwich Workshop in 1993.

“The Deceiver” won the Gold Medal in Oil at the 11th Annual Cowboy Artists of America Show & Sale in 1976 at the Phoenix Art Museum. It should be noted that 1976 was the first year Tom Lovell participated as an artist in a CAA Show & Sale; not bad for a rookie member at the time! Subsequently, this masterwork has been exhibited at the “Clymer, Lovell & Teague” exhibition at the Thomas Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, OK; the “Grand Opening Exhibition” of the CAA Museum in Kerrville, TX; the “West-Southwest Exhibit” at the Albuquerque Museum of Art, History & Science; and at “A Salute to CAA and a Patron, the late Eddie Basha: 50 Years of Amazing Contributions to the American West” in 2016 at Western Spirit Scottsdale’s Museum of the West.

24”h x 38”w

24”h x 38”wMost Indians living along the twisting course of the upper Missouri River had not seen white men prior to the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804-1806. A few scruffy French voyagers had come down from Canada to trade with villages on the northeastern edge of the Plains, but the arrival of the Lewis and Clark party was the first time a significant number of Indians came in contact with this tribe of men who appeared so different from themselves. Great excitement was created by the arrival of these strange visitors from the East. The manner of dress of the expedition commanders was most unusual, and they brought with them things which inspired awe.

Part of the mission of the Corps of Discovery was to make friends of the native people encountered on the long journey to the Pacific. Here, Captain Clark, in full dress uniform, entertains a band of Indians with a demonstration of a rifle which fires multiple times from the power of a compressed air flask attached beneath the breech.

Captain Clark’s Air Gun (Study)

Artist: Tom Lovell, CA (1909-1997)

Most Indians living along the twisting course of the upper Missouri River had not seen white men prior to the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804-1806. A few scruffy French voyagers had come down from Canada to trade with villages on the northeastern edge of the Plains, but the arrival of the Lewis and Clark party was the first time a significant number of Indians came in contact with this tribe of men who appeared so different from themselves. Great excitement was created by the arrival of these strange visitors from the East. The manner of dress of the expedition commanders was most unusual, and they brought with them things which inspired awe.

Part of the mission of the Corps of Discovery was to make friends of the native people encountered on the long journey to the Pacific. Here, Captain Clark, in full dress uniform, entertains a band of Indians with a demonstration of a rifle which fires multiple times from the power of a compressed air flask attached beneath the breech.